In this extract from essay collection Upturn, the actor considers the disruptions of the pandemic and the renewed fervour for social and economic justice

The other day I had to go into town for a dental appointment. I put on all sorts of lovely clothes as if I were going out to dinner and an opening night. The prospect of being out and about was both exhilarating and daunting. I so desperately wanted to be among people and in the city, but I’d also completely forgotten what an event was. The dentist did not seem surprised by my sartorial over-commitment – but then, I was not the first patient he had seen since lockdown.

As a person working in the arts sector, the lockdown was strangely familiar on one level – a lot of actors get stuck in a kind of limbo waiting for someone else to give them permission to do what they are good at. It was as if we were all waiting by the phone for our agent to call. It was also strangely unfamiliar because the community that holds us together, the audiences, as well as the changing of the shows and the new releases, were all put on hold too. The flow between us all was severely affected, and I was both heartened and horrified when it began to surface online. Heartened because the urge to express ourselves and the desire to communicate seems undaunted by anything. Horrified because the worst place to rehearse and perform is alone in the mirror, and sometimes the phone is just a mirror.

It was amazing, though: the opera singers belting it out on their balconies, the dancers doing their solos in their living rooms, the DJs setting up on the verandahs of their apartments. Communication is definitely a need and not a want. And talent has to express itself. That need is like the roots of a tree seeking space and nutrition, and that single cell in the root hair that is the porous gateway between the soil and the plant – that exists in all of us, in our need to communicate and make shared sense. The porous gateway between audience and artist is just that – a two-way street where both seemingly separate worlds are alive together. The pub choir where everyone got on a group Zoom and sang. For themselves? Yes. For each other? Yes. For the uni- verse? Yes. Wonderful space that came alive and thrived and tried to reach across the divide.

Covid-19 has made one thing terribly clear – government is not the same as business. The role of government is to regulate and guide the increasingly complex social landscape. Business is only a part of that landscape. Health, infrastructure, the legal system, education: these are not businesses. First and foremost they are part of society, part of our duty to each other and to the system that we are all beneficiaries of – or should be beneficiaries of – but that is a whole other catastrophe that has been made awfully clear in the last six months.

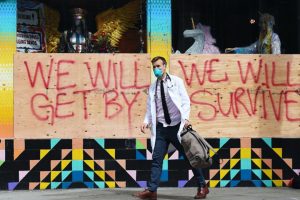

So what has Covid-19 ripped open? The fragility of social space and the robustness of our need to share. The catastrophic misdirection of the past 30 years of economic and social planning (the guiding non-principle being that there is no such thing as society). No, short of nostalgia and regret, Covid-19 has ravaged the whole idea of small government, and highlighted the importance of social and economic justice. Powerfully illustrating these concerns, the most recent wave of Black Lives Matter (BLM) activism has underlined the need for an equitable and humane social plan.

For the arts, I fear the good old days of root and soil porous gateway-ism are a thing of the past. The relationship between artist and audience has changed fundamentally. The tools of the future on hand today, from selfies to Zoom, are just awkward attempts to grab back the surface appearance of connectivity. Real connectivity will need to find a new way. The good news is, it will – and it will be fascinating and illuminating and confronting.

My guess is, it will be in the event. The fabulous event of coming together; gathering and going out (even to the dentist) and I think it will be in politics first and foremost, in argument and protest. The iconic images and moments of lockdown for me are: “I can’t breathe” written on the face masks of the BLM protesters; that courtyard in Italy filled with singing neighbours; that anonymous Lady Godiva protester in Portland, sitting stark naked in front of the police; the quiet skies; and the self-proclaimed business-genius president of the most important democracy in the world recommending ingesting or injecting disinfectant.

The common link between these iconic events is profoundly political, because the political space is where we gather, and with rhetoric or imagery or gesture, with some kind of enhanced reality (let’s call it a performance) we express what we need to say. Each one of these is startling. There is a profound element in them that is revelatory. We engage with the performance of the gesture and the whole of it is greater than the sum of its parts. I think this need to gather is fundamental to who we are, and it has been stymied by Covid-19 but also underlined by it, and that need in us for community addresses the difficult lesson we have to learn: business is not government and government is not a business. The biggest choice as governments began thinking about easing lockdowns, the choice that really seems to divide us deeply, is that between community and economy.

Like life, art can be a business. But like life, art is not all business – and it is that endangered space where life and art are not just about money that government is there to help safeguard.

• This is an edited extract from the chapter Australian Stories by Cate Blanchett and Kim Williams in Upturn: A Better Normal After Covid-19, edited by Tanya Plibersek, NewSouth, November 2020, $32.99 RRP