Researchers using enhanced, rare footage of a transport to a Nazi death camp have been able to identify some passengers, including children who survived.

AMSTERDAM — They appear for less than three seconds in the film footage, faces distorted through the window glass. Small cherubs, staring out confusedly at a chaotic scene on the railway platform. In a few moments, the train will roll out, and they will be on their way to a Nazi death camp.

For decades, these nameless children have been among the anonymous victims of hate captured in rare footage that showed the Nazis shipping off people in cattle cars to be murdered.

The footage is part of a compilation known as the Westerbork Film, named after the Nazi transit camp from which Dutch Jews were deported to death camps in occupied Poland and Germany. Shot in 1944, the footage has been used in countless war documentaries, the unknown passengers serving as the public faces of the millions sent to “the East.”

Now two Dutch researchers, authors of a new book about the film, have identified two of the children behind the glass, along with at least 10 other individuals captured on film, providing a more detailed, personal view of lives ravaged by the Holocaust.

The children were 3-year-old Marc Degen and his 1-year-old sister, Stella Degen. The researchers believe that their cousin, Marcus Simon Degen, who would soon turn 4, was also on the train with them. The children were deported with their parents on May 19, 1944, to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany. The scene was captured by Werner Rudolf Breslauer, a German-Jewish inmate, who was assigned to film aspects of the camp for propaganda purposes.

All three of the children would survive the war, even after their parents were taken from them, because of the efforts of another prisoner who hid and cared for them. Two of them are still alive to bear witness to the horrors they suffered.

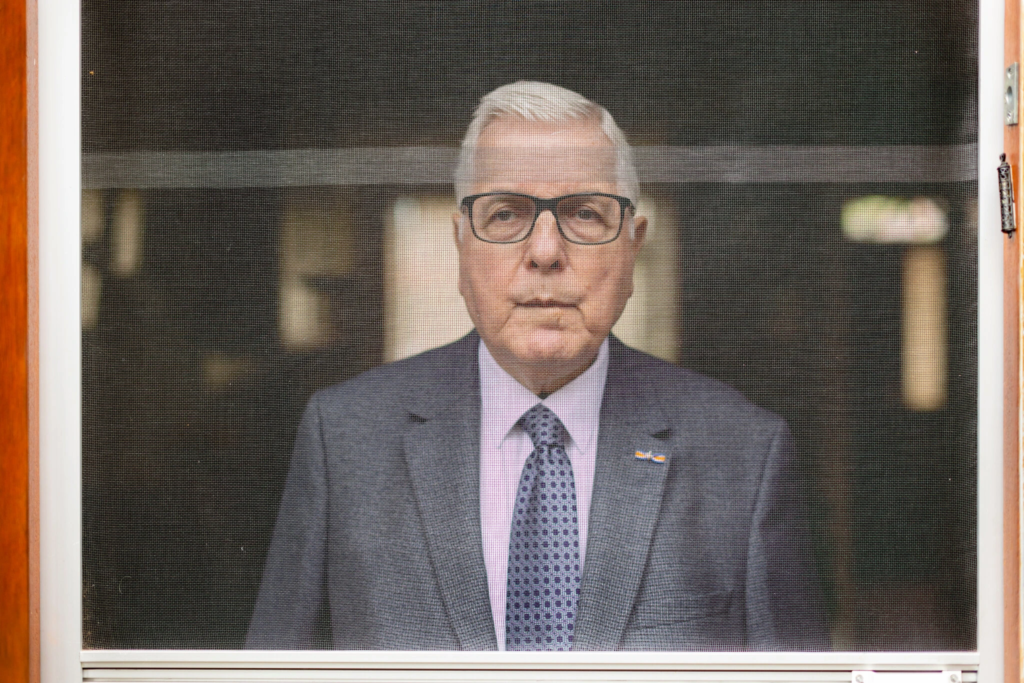

“Now I feel that I can shout from the roofs, I’m still here, the Nazis didn’t get me,” said Marc Degen, who recently turned 80, in an interview from his home in Amstelveen, a leafy suburb of Amsterdam. His sister, now Stella Fertig, lives in Queens, N.Y. Their cousin, Marcus Simon, also survived the war, but he died in 2006.

The researchers, Koert Broersma and Gerard Rossing, will reveal the additional identities of other people in the film as part of the launch of their new book, “Kamp Westerbork gefilmd,” on Tuesday at the Remembrance Center Camp Westerbork, a museum and memorial site in Drenthe, the Netherlands.

The book’s publication coincides with the release of a newly restored, cleaned and digitized version of the Westerbork Film, created by the Dutch media archive, Sound and Vision. The documentary, which originally totaled about 80 minutes, is now 2.5 hours long, depicting various aspects of life at the transit camp, including some recently discovered footage. The film with the new footage has also been set to the correct speed (so people walk at a normal pace), which makes its run-time longer. It will be shown at the Camp Westerbork Memorial Center in the Netherlands beginning Wednesday.

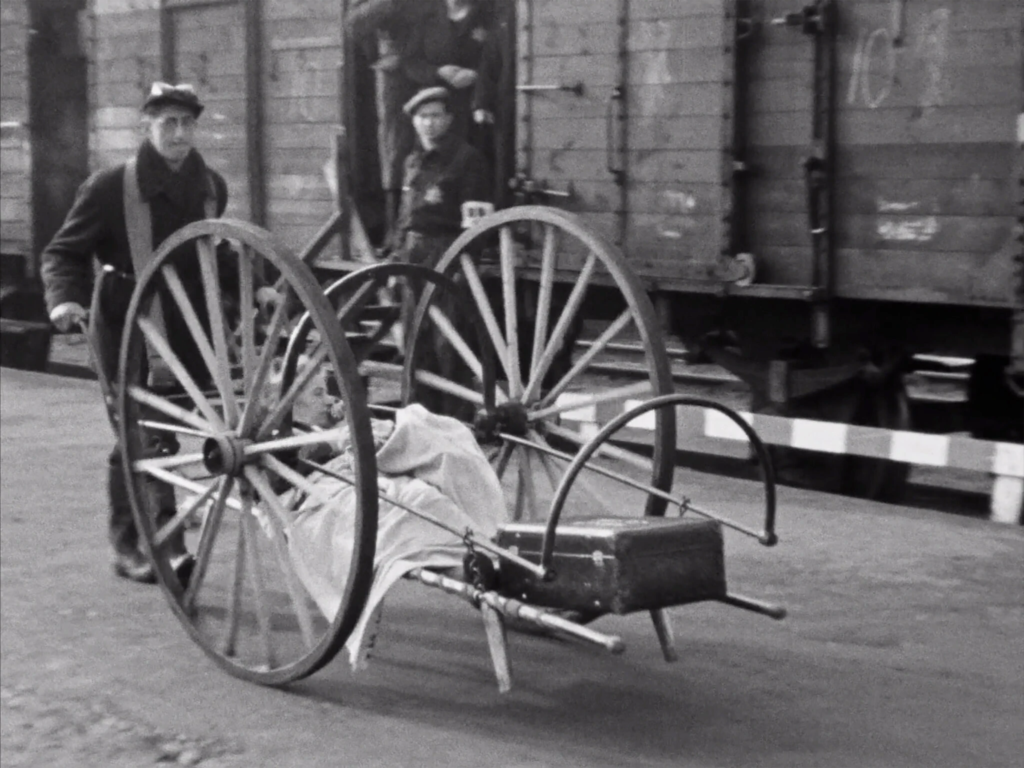

Before these recent new identifications, only two passengers of the nearly 1,000 on board the transport had ever been named: A terrified Sinti girl who peers out from between two cattle car doors was recognized as Settela Steinbach by a Dutch journalist in 1992. Broersma and Rossing previously discovered that a woman pushed in a kind of wheelbarrow gurney was Frouwke Kroon, a 61-year-old from Appingedam, a small city in northeastern Netherlands, who was killed in Auschwitz three days later.

“Putting a name to a face really makes this monolithic huge tragedy understandable and relatable,” said Lindsay Zarwell, a film archivist at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “To have a first name, and last name, and know a little bit about where the person came from and what happened to them, makes it real. It sometimes gives me goose bumps. It also literally alters what you’re seeing.”

The restoration of the film and the investigation into its history were a joint effort of four Dutch historical organizations, Sound and Vision, Camp Westerbork, the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, and the Jewish Cultural Quarter in Amsterdam.

“The four institutes that look after this film wanted to make sure that the story, and the whole story, is told,” said Valentine Kuypers, a curator at Sound and Vision.

With the same goal in mind, Broersma and Rossing decided to dig deeper into the history of the film, which was made at the behest of the camp’s SS commander, Albert Konrad Gemmeker. He hoped to send it to Nazi officials who were planning to close down the transit camp. By spring 1944, 90 percent of the Jews from the Netherlands had already been deported.

“It was made as a P.R. film,” Broersma said. “Gemmeker was afraid of being sent to the Eastern Front because Westerbork had lost its purpose as a transit camp.” The SS commander instructed Breslauer to capture images of people working, because he, “wanted to show that Westerbork was still important as a work camp.”

Breslauer filmed for months with materials purchased by the SS. But he went beyond the limits of his assignment, documenting not just work, but also three transports of Jews, two incoming and one departing.

The departing transport that carried the Degens was divided into two sections. Third-class passenger cars, with windows and seating, were headed to Bergen-Belsen in Germany, where some inmates were held as “trading material,” and swapped for German prisoners.

The other half of the train, windowless cattle cars, went to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where the vast majority of passengers were gassed on arrival.

Did Gemmeker, the camp commander, instruct Breslauer to film the transport? Broersma doesn’t believe so. He interviewed Breslauer’s daughter, Chanita Moses, in the 1990s, and she said her father shot the transports without the commander’s approval, leading to arguments.

“She told us that her father was determined to leave an eyewitness account on film,” Broersma said. “He was eager to shoot images of these transports because they were a definite proof of the Holocaust.”

The film contains about eight minutes of transport footage. Travelers with yellow stars affixed to their coats, bags dangling from their shoulders, clamber into open compartments. Some look bewildered but others seem strangely cheerful — the source of much subsequent scholarly debate. The elderly and disabled can be seen sitting on a train floor, among straw and baggage. When the commander gives the sign, the massive train doors are cranked shut.

Shooting ended abruptly, for unknown reasons. The raw material was never edited. Breslauer lost whatever exemption he had for serving as filmmaker and he and his wife and three children were deported to Theresienstadt in September, then on to Auschwitz, where his wife and two sons were gassed. He died in an unknown location in February 1945; his daughter survived the war.

Some film reels were smuggled out of the camp, Broersma said; after the war they ended up at the NIOD, where historians viewed them first.

“The transport footage was used in Alain Resnais’s famous ‘Night and Fog,’ which is one of the most important Holocaust documentaries,” said Frank van Vree, director of the NIOD Institute, in an interview, “and from then on it was used in so many documentaries, I don’t even know how many.”

In 1988 the raw footage was spliced together in no particular order to make an 80-minute reel. That film became the most-requested material from a million-film collection of the Dutch film archives, Kuypers, the curator, said. Last year, the Dutch film director Robert Schinkel released a short film about the camp’s SS commander, Gemmeker, that incorporated two minutes of footage from the Westerbork film that was colorized by his production company, The Media Brothers, with a special effects partner, Planet X.

In 2017, when Kuypers and her team at Sound and Vision requested all the material from the film archives to begin their restoration, they made a discovery: two original reels. These sharper and clearer images enabled Broersma and Rossing to read names and birth dates written on baggage, which provided them the identities of other passengers.

They could also very clearly see three small children in Wagon 3. They figured out the children’s identities through a process of elimination: The Degens were the only family with three children under the age of 6 on the Bergen-Belsen transport.

The children were separated from their parents at the camp; their mothers were sent to work in salt mines and their fathers were deported to another camp, Sachsenhausen. The fathers both died in 1945; the mothers were sent to Sweden in exchange for German prisoners of war who were being held there.

The toddlers, left behind in the barracks with other orphaned children, were given no food or supervision. A Polish Jewish nurse, Luba Tryszynska, took it upon herself to care for them, scrounging and begging for enough tidbits to keep them from starving, and hiding them under beds, away from the SS. The British liberated Bergen-Belsen on April 14, 1945; all three were eventually reunited with their mothers.

Stella Fertig said she remembers nothing from the war years. “People say, ‘It’s better that you don’t know,’” she said. “But I would like to know a little bit more.”

She and Marc Degen were unaware of the film, or their role in it, until the authors contacted them. When Marc saw the footage, he recognized himself and his mother in the right window of the train compartment.

“I was overwhelmed to see myself as a little boy being transported with my family,” he said. “I feel privileged that at 80 years old I feel healthy, in my head and in my body, and that I can talk about this today.”