It’s long past time to hold Beijing accountable for human rights violations.

The woman’s voice cracks as she calls for the souls of the dead to rest in peace. More than three decades since their loved ones were killed by Chinese security forces in the Tiananmen Square massacre of June 4, 1989, family members vowed in a recording last week to press on “until the day of justice arrives.”

On the 35th anniversary of the fatal crackdown on unarmed protesters, Chinese president and Communist Party leader Xi Jinping has silenced discussion in China of what happened in 1989. We can’t let him silence us too.

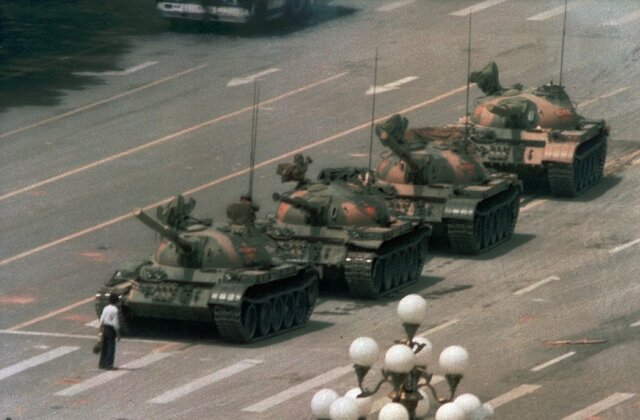

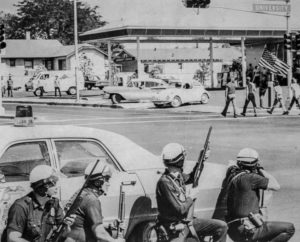

We must remember the students, workers, journalists and others who gathered peacefully in Beijing at a moment of political fluidity in April 1989, demanding free speech, economic reform, greater liberties and an end to corruption. As the protests grew, the government imposed martial law the following month. When protesters didn’t disperse, authorities killed hundreds or perhaps thousands of unarmed citizens in Beijing and other cities. We don’t know exact numbers because China suppressed them, hiding the death toll and scope of the nationwide crackdown.

Chinese leaders have had 35 years to face up to the past. Yet they steadfastly refuse to do so, presumably fearing that truth and accountability for Tiananmen — and for so many other violations of Chinese citizens’ basic human rights — will threaten their iron grip on power.

Unfortunately, democratic nations – including the United States – have allowed China’s economic and strategic importance on the world stage to take precedence, enabling impunity for the crimes of Tiananmen by failing to impose meaningful consequences on the Chinese government.

Issuing statements commemorating the crackdown, as the U.S. and others have done in the past, is a symbolic but insufficient gesture. China’s leaders have committed even worse human rights violations in the years since Tiananmen, including genocide against the minority Uighurs in western China, in part because they face few to no domestic or international consequences for doing so. Democracies need to demand the release of those wrongfully detained in China, and accountability for China’s crimes against humanity. One option would be establishing international tribunals to investigate these crimes.

There are 27 Chinese citizens serving sentences or under detention in mainland China and Hong Kong for their involvement in the protests or commemoration of 1989, according to the global Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders; three other Tiananmen veterans were “persecuted to death” by authorities, including 2010 Nobel Peace laureate Liu Xiaobo.

In Hong Kong, once an island of free expression, 1 million people gathered in Victoria Park 35 years ago to protest the crackdown. For decades, tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of Hongkongers marked the event in an annual candlelight vigil at Victoria Park – until those events were banned in 2020.

Xi’s efforts to control past, current and future critiques of the government aren’t limited to June 4, or confined to the country’s borders. When years of China’s draconian “zero-COVID” controls prompted peaceful protests in China, authorities squashed dissent. Peng Lifa, who hung a banner on a bridge in Beijing calling for an end to the lockdown and for democracy, was taken by police in October 2022 and hasn’t been heard from since. Other protesters held up blank pieces of paper across China in November 2022, but they too were persecuted and references to their efforts were censored.

Increasingly, commemorations of June 4 and other Chinese government assaults on human rights take place outside China. People will gather this year from Toronto to Tokyo. In Hong Kong, courageous individuals have attempted private remembrances or public acts, including publishing a newspaper with a blank front page ahead of June 4. As Beijing increasingly seeks to silence Chinese overseas, those who join these gatherings must be wary of state surveillance. At a Tiananmen commemoration in California last week, organizers obscured some participants’ identities, fearful of reprisals against those people and their family members still in China.

Even as Xi increases repression domestically and internationally, the Tiananmen Mothers have called for transparency and accountability regarding June 4, and for Chinese authorities to respect the rule of law.

The mothers’ photos of their children who died in 1989 are now faded, but they reflect the spirit of people inside and outside China bravely demanding respect for their human rights. Their actions should galvanize leaders of democracies into action. Even one more year of impunity for the Chinese Communist Party will have devastating consequences for human rights.

Sophie Richardson is a visiting scholar at Stanford University’s Center on Democracy, Development and Rule of Law, and the former China director at Human Rights Watch.