This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

There will be at least 15,000 instances of viruses leaping between species over the next 50 years, with the climate crisis helping fuel a “potentially devastating” spread of disease that will imperil animals and people and risk further pandemics, researchers have warned.

As the planet heats up, many animal species will be forced to move into new areas to find suitable conditions. They will bring their parasites and pathogens with them, causing them to spread between species that haven’t interacted before. This will heighten the risk of what is called “zoonotic spillover,” where viruses transfer from animals to people, potentially triggering another pandemic of the magnitude of Covid-19.

“As the world changes, the face of disease will change too,” said Gregory Albery, an expert in disease ecology at Georgetown University and co-author of the paper, published in Nature. “This work provides more incontrovertible evidence that the coming decades will not only be hotter, but sicker.”

“We have demonstrated a novel and potentially devastating mechanism for disease emergence that could threaten the health of animals in the future and will likely have ramifications for us, too.”

Albery said that climate change is “shaking ecosystems to their core” and causing interactions between species that are already likely to be spreading viruses. He said that even drastic action to address global heating now won’t be enough to halt the risk of spillover events. “This is happing; it’s not preventable even in the best-case climate change scenarios, and we need to put measures in place to build health infrastructure to protect animal and human populations,” he said.

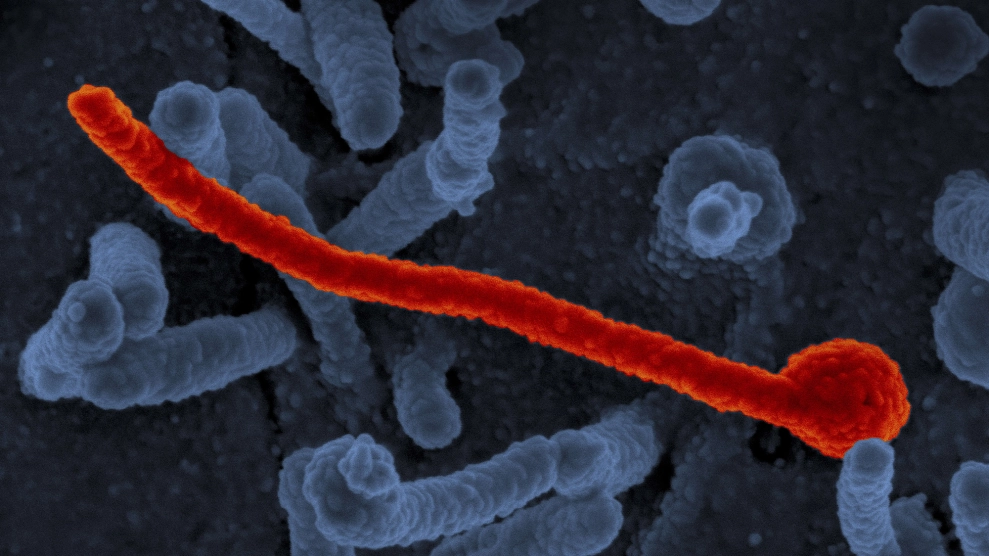

The research paper states that at least 10,000 types of viruses capable of infecting humans are circulating “silently” in wild animal populations. Until relatively recently, such crossover infections were unusual but as more habitat has been destroyed for agriculture and urban expansion, more people have come into contact with infected animals.

Climate change is exacerbating this problem by helping circulate disease between species that previously did not encounter each other. The study forecast the geographic range shifts of 3,139 mammal species due to climatic and land use changes until 2070 and found that even under a relatively low level of global heating there will be at least 15,000 cross-species transmission events of one or more viruses during this time.

Bats will account for the majority of this disease spread because of their ability to travel large distances. An infected bat in Wuhan in China is a suspected cause of the start of the Covid pandemic and previous research has estimated there are about 3,200 strains of coronaviruses already moving among bat populations.

The risk of climate-driven disease is not a future one, the new research warns. “Surprisingly, we find that this ecological transition may already be under way, and holding warming under 2C within the century will not reduce future viral sharing,” the paper states.

Much of the disease risk is set to center upon high-elevation areas in Africa and Asia, although a lack of monitoring will make it difficult to track the progress of certain viruses.

“There is this monumental and mostly unobserved change happening within ecosystems,” said Colin Carlson, another co-author. “We aren’t keeping an eye on them and it makes pandemic risk everyone’s problem. Climate change is creating innumerable hotspots for zoonotic risk right in our backyard. We have to build health systems that are ready for that.”

Experts not involved in the research said the study highlighted the urgent need to improve processes designed to prevent future pandemics, as well as to phase out the use of the fossil fuels that are causing the climate crisis.

“The findings underscore that we must, absolutely must, prevent pathogen spillover,” said Aaron Bernstein, interim director of the center for climate, health, and the global environment at Harvard University. “Vaccines, drugs and tests are essential but without major investments in primary pandemic prevention, namely habitat conservation, strictly regulating wildlife trade, and improved livestock biosecurity, as examples, we will find ourselves in a world where only the rich are able to endure ever more likely infectious disease outbreaks.”

Peter Daszak, president of EcoHealth Alliance, a nonprofit that works on pandemic prevention, said that while human interference in landscapes has been understood as a disease risk for a while, the new research represents a “critical step forward” in the understanding of how climate change will fuel the spread of viruses.

“What’s even more concerning is that we may already be in this process—something I didn’t expect and a real wake-up call for public health,” he said. “In fact, if you think about the likely impacts of climate change, if pandemic diseases are one of them, we’re talking trillions of dollars of potential impact.

“This hidden cost of climate change is finally illuminated, and the vision this paper shows us is a very ugly future for wildlife and for people.”