Columbus Day began as a celebration of Italian immigrants who faced persecution in the U.S. But for many it’s now a symbol of the colonization and oppression of Indigenous people.

Was Christopher Columbus a heroic explorer or a villainous murderer? It depends on who you ask. The tussle over how or whether the United States should commemorate the Italian navigator’s 1492 landing in the Americas has fueled controversy for generations.

A federal holiday celebrated the second Monday of each October, Columbus Day arose out of a late 19th century movement to honor Italian American heritage at a time when Italian immigrants faced widespread persecution.

But the holiday has since come under fire as a celebration of a man whose arrival in the Americas heralded the oppression of another group of people: Native Americans. In recent decades, it has been replaced by Indigenous Peoples’ Days in many states and cities.

In 2021, the U.S. will celebrate its first national Indigenous Peoples’ Day on October 11 in a commemoration President Joe Biden proclaimed as a day to honor “our diverse history and the Indigenous peoples who contribute to shaping this Nation.” Biden also issued a Columbus Day proclamation acknowledging the contributions of Italian Americans as well as “the painful history of wrongs and atrocities” that resulted from European exploration. Here’s how Columbus Day began, and how the movement to replace it has gained momentum.

Early Columbus Day celebrations

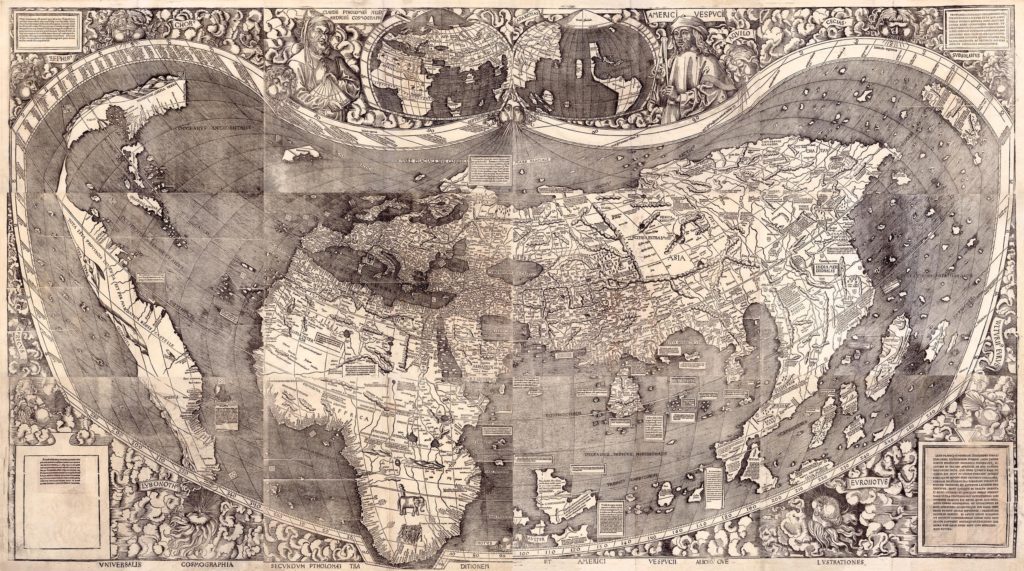

On October 12, 1492, after a voyage of 10 weeks, Christopher Columbus’ crew spotted the New World. The Italian navigator’s three ships, sailing at the behest of the Spanish crown, would soon land, likely on an islandknown to its Lucayan residents as Guanahaní. Columbus christened it San Salvador.

It was the beginning of a new era in the history of the Western Hemisphere—an event commemorated in the U.S. since the nation was founded in 1776. But before the late 19th century, the celebrations were mainly limitedto Catholic and Italian American enclaves on the East Coast, where many embraced Columbus as an intrepid explorer who embodied progress and bravery. For these people, Columbus represented their indelible contribution to a society that viewed both Catholics and Italian Americans with suspicion.

Celebrations of Columbus gained momentum as Italian immigration grew from a trickle to a flood. Beginning in the 1880s, Italian immigrants began pouring into the U.S. in search of opportunity and a better life. But the new arrivals were not welcomed by all. Maligned as sinister and criminal, Italian immigrants were the focus of increasing bigotry.

In 1890 anti-Italian sentiment boiled over in New Orleans after police chief David Hennessy, reputed for his arrests of Italian Americans, was murdered. In the aftermath, more than a hundred Sicilian Americans were arrested. When nine were tried and acquitted in March 1891, a furious mob rioted and broke into the city prison, where they beat, shot, and hanged at least 11 Italian American prisoners. None of the rioters who lynched the Italian Americans were prosecuted. It remains one of the largest mass lynchings in the nation’s history.

From international incident to a nationwide holiday

The brutal killings created tit-for-tat tensions between the U.S. and Italy, which called for reparations for the murders. At first, the U.S. refused, prompting Italy to recall its ambassador and cut off diplomatic relations. The U.S. reciprocated.

But eventually, in an attempt to appease Italy and acknowledge the contributions of Italian Americans on the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ arrival, President Benjamin Harrison in 1892 proclaimed a nationwide celebration of “Discovery Day,” recognizing Columbus as “the pioneer of progress and enlightenment.” Eventually, the nations mended their relationship and the U.S. paid $25,000 in reparations.

In the decades after the mass lynching, Italian American advocates pushed for a nationwide holiday, and states slowly began to adopt it. In 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt designated it a national holiday, and in 1971 Congress changed the date from October 12 to the second Monday of October. The holiday, writes historian Bénédicte Deschamps, “allowed Italian-Americans to celebrate at the same time their Italian identity, their Italian-American group specificity, and their allegiance to America.”

The push for Indigenous Peoples’ Day

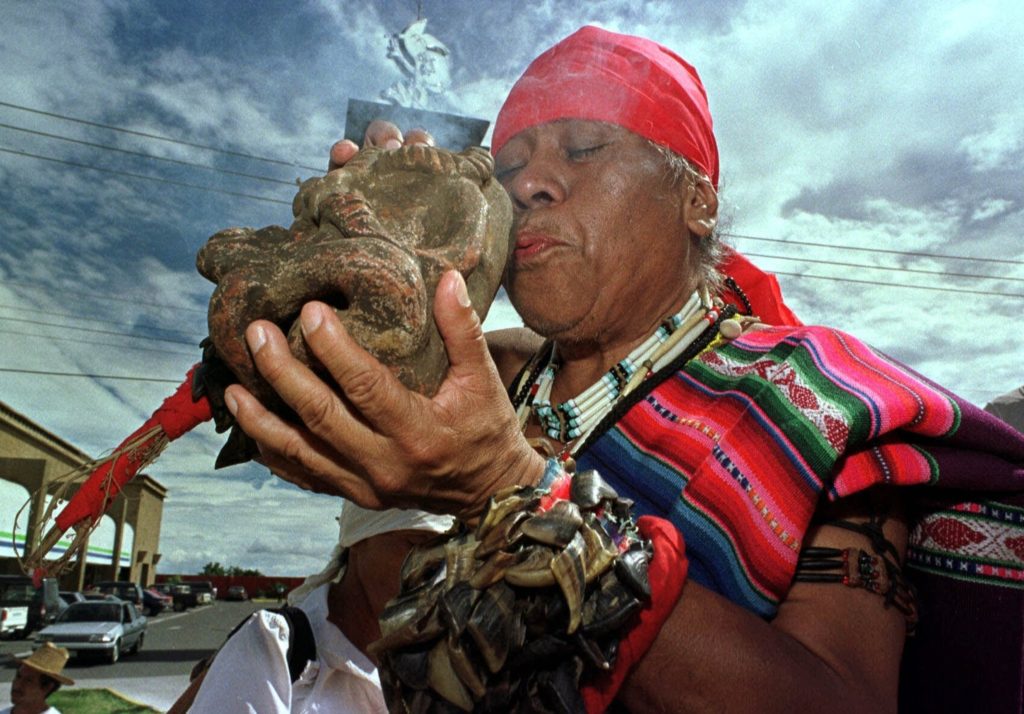

Columbus Day celebrated Italians. But for many with Indigenous ancestry, it was a slap in the face—a celebration of invasion, theft, brutality, and colonization. Columbus and his crew enabled and perpetrated the kidnapping, enslavement, forced assimilation, rape and sexual abuse of Native people, including children; the Native American population shrankby about half after European contact. For Indigenous Americans, the landing celebrated by some as a day of triumphant discovery was the beginning of an incursion onto land that had long been their home.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Pan-Indian and Red Power movements brought together Native Americans who began to draw attention to the hero’s sordid history. In 1970, for example, anonymous protesters scrawled Red Power slogans on the statue of the navigator in the middle of New York’s Columbus Circle ahead of Columbus Day celebrations. The New Yorker reported on the incident, calling it “a topic to joke about safely” among white politicians on the viewing stand for that day’s festivities—an indication of just how far the movement would have to go to change the nation’s view of Columbus.

In the 1980s and 1990s, protests against the holiday grew. In 1990, ahead of the 100th anniversary of the Wounded Knee Massacre, in which U.S. soldiers killed some 300 Lakota people, Native American publisher Tim Giago urged South Dakota’s governor to declare it a year of reconciliation and change Columbus Day to a holiday called Native American Day. The governor, George S. Mickelson, agreed, and the holiday has replaced Columbus Day in the state ever since.

Two years later, ahead of the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ landing, Indigenous groups lobbied the United Nations and local governments not to participate in international celebrations. A group called Resistance 500 formed in the Bay Area in response to the plans—such as an event in which replicas of Columbus’ ships sailed into San Francisco Harbor. Berkeley’s city council recognized the group as a task force and unanimously adopted its suggestion of replacing Columbus Day with a holiday called the Day of Solidarity with Indigenous People. The Indigenous activists won another victory when the ships’ journey was called off in the face of growing pressure.

Columbus Day today

Though Italian American groups protested the move, it fueled ongoing activism among Indigenous people. In the 2010s, Indigenous Peoples’ Day —known by some as Native American Day—gained steam as it was adopted by scores of cities around the nation. It is now a paid state holiday in Alaska, Iowa, Maine, Minnesota, New Mexico, Nevada, North Carolina, Oregon (which celebrates both Columbus Day and Native American Day), South Dakota, Vermont, and Wisconsin.

In addition, multiple states have stopped celebrating Columbus Day altogether. According to Pew Research, only 21 states offer their government workers paid holidays on the second Monday in October.

Even Columbus, Ohio, the largest city named after the Italian navigator, has changed its tune: In 2018, it stopped celebrating Columbus Day, and in 2020 it declared October 12 Indigenous Peoples’ Day. “It’s impossible to think about a more just future without recognizing these original sins of our past,” Columbus City Council president Shannon Hardin reportedly said at the meeting.

In a similar spirit of reckoning, in April 2019 New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell apologized for the 1891 lynchings of Italian Americans, more than a century after the incident. “Some people didn’t want me to make this apology today,” Cantrell said at the time. “But…I have a responsibility to deal with what’s in front of me, and to speak honestly about the challenges we face, those that shape our history and, more importantly, our future.”