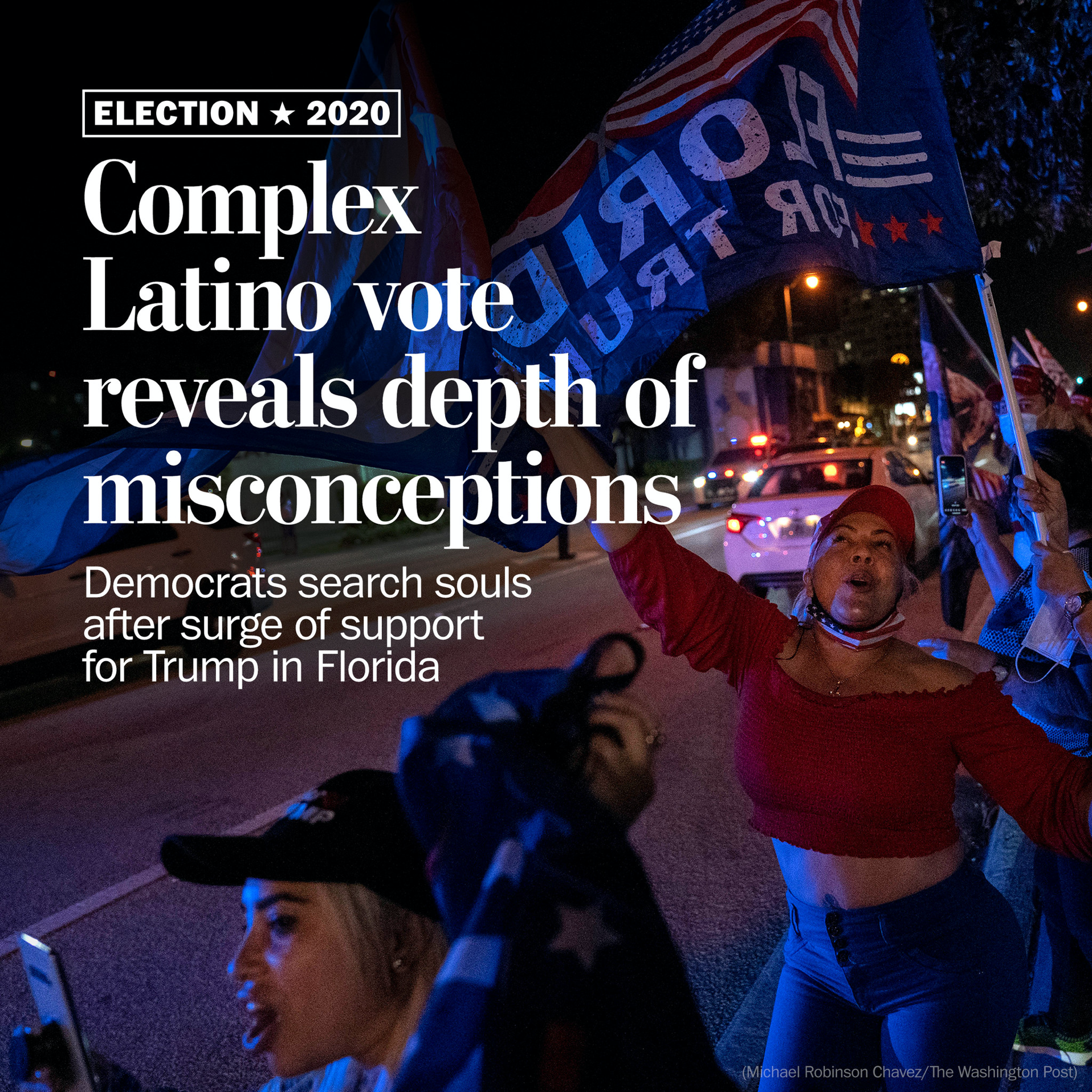

The nuanced and sometimes dissonant political preferences shown by Latino voters in the 2020 presidential election have sparked bewilderment and soul-searching among Democrats as the party lost significant ground with Latinos in Florida and Texas over the past four years.

The preliminary results underscored the extent to which the broad range of Latino communities, from Cuban Americans in South Florida to Mexican Americans in Arizona, have been often taken for granted and misunderstood by the Democratic political establishment.

In Florida, nearly half of Latino voters cast ballots for President Trump, according to network exit polling.

In Arizona, exit polls showed more than six in 10 Latino voters cast ballots for Democratic nominee Joe Biden, and 56 percent did so in Nevada.

In the heavily Latino Rio Grande Valley in Texas, Trump lost rural Starr County — which is 96 percent Hispanic — by just 5 percentage points compared with a loss by 60 points in 2016.

The key to making sense of those trend lines, political experts and community organizers say, is to throw out the idea that Latinos compromise one single electorate. Although in the aggregate they tend to lean Democratic, the political calculations of Latinos are shaped by where they live, their ancestry, age, education, income and faith, among other factors in a group of approximately 32 million citizens, all with distinct political inclinations.

“In Arizona when we say ‘Latinos,’ we’re talking about people of Mexican descent, either longtime residents that were here before Arizona was a state and also new immigrants that have since come from what is now Mexico,” said Joseph Garcia, executive director of Chicanos Por La Causa Action Fund in Phoenix. “When you say ‘Latinos’ in Florida, you’re talking largely about people of Cuban descent with more of a conservative streak: Venezuelans, Puerto Ricans among others. ”

State by state, the strength of Biden’s support among Latinos appears related to the strength — or absence — of long-term outreach efforts.

The Democratic Party’s failure in Florida to build a permanent campaign infrastructure to target Latinos left the Biden campaign at an early disadvantage, said Fernand Amandi, a Democratic pollster and strategist in the state. Amandi said he has warned Democratic leaders about this election cycle after election cycle, but has seen little change.

Although Cuban Americans, who tend to live in Miami-Dade County, have historically been Republican-leaning voters, their commitment to the GOP is not monolithic. Meanwhile, Puerto Ricans, whose numbers have grown in the state in recent years, are often assumed to be Democrats. That is not always the case among many evangelical Protestants and those who have recently moved from Puerto Rico.

Polling in September sounded the alarm that Biden was significantly underperforming among Florida’s Latino voters, which sent the campaign scrambling, Amandi said.

“To their credit, they turned around the engagement. It went from zero to 80 overnight. But they were trying to do in six weeks what the Republican have been doing for five years,” he said.

Amandi pointed to the vigorous turnout operation in Nevada powered by the Culinary Union, in which members take paid temporary leave from their jobs as housekeepers and restaurant servers to spend weeks or months door-knocking for political candidates to encourage voter participation. Their work has been credited with helping make Nevada a more favorable political landscape for Democrats. About 54 percent of the union’s 60,000 hospitality workers are Latino.

“It’s not that complex. And that’s why it’s so horrifyingly frustrating when it doesn’t happen,” Amandi said.

This cycle, those gaps left Biden vulnerable to disinformation and mischaracterizations, including claims that he was a socialist, which spread widely in Miami-Dade and were largely unchallenged until the final stretch of the campaign.

“It is harder for those allegations to stick if you’re in the community for a sustained period, unlike when you leave the battlefield and your opponents define you in a vacuum,” Amandi said. “The Democrats need to be on the ground and in the community, and they’re just not. When you’re on the ground and engaged, they’re not going to be able to pull those kinds of political tricks on you.”

Social media researchers have seen a wide range of misinformation targeting Spanish-speakers in the United States. In recent years, technology companies have put in place mechanisms to combat misinformation about the election, the pandemic and other topics. But misinformation has proliferated regardless because content moderation is less developed in other languages besides English.

But if Florida provided a nightmare scenario for the Biden campaign, the situation in Arizona, once a conservative stronghold, offered a possible glimmer of hope.

There, Biden was leading Trump, 51 percent to 47.6 percent, with an estimated 83 percent of votes counted. Biden has proved to be strong with Mexican American

Many local political experts and activists see Biden’s strength in the state as the culmination of a decade of political organizing by grass-roots Latino organizations and nonprofit organizations in Maricopa County, a onetime conservative bastion that includes Phoenix. Animated by the battle in 2010 over SB 1070 — a hard-line anti-immigrant law that drew national condemnation — countless young activists have helped transform the region politically with an intense focus on bringing young, Mexican American first-time voters into the political process.

And they have done so largely irrespective of the national Democratic Party, Garcia said. The Democratic Party has been reluctant to invest resources in the state’s political infrastructure, preferring instead to invest dollars in courting likely voters in the Midwest, he said.

It is a familiar story to Latino activists: Because conventional wisdom says Latino voters turn out in unreliable numbers, Garcia said, campaigns often do not invest in outreach. But these voters do not turn out because candidates do not reach out for their vote.

“Arizona might be the great savior for Joe Biden, which is ironic because Joe Biden did very little campaigning here,” Garcia said.

“Chicanos Por La Causa is the second-largest Latino organization in the nation. We were never reached out to by the Biden campaign or the Democratic Party to see what we could do for them. And we were surprised by that,” he said. “But we went ahead and took a proactive approach to getting more Latinos registered and voting. If Latinos are going to wait for the Democratic Party to save them, they’ll be waiting a long time.”

Matt Barreto, a pollster for the Biden campaign, said lackluster support for Biden in Miami-Dade was partially because White voters did not turn out for Democrats at the rate they had expected. He cautioned that results in Florida do not necessarily reflect Biden’s strength among Latinos elsewhere.

In particular, he praised the work of Biden campaign staffers in Arizona.

“I understand if you’re in Florida and you’re in Miami, you’re frustrated,” he said. “But this is not something that was automatically going to be fixed based on who someone hired or what ad they ran.”

In the final days before the election, the Biden campaign said it believed it would be able to bring together a base of voters that included young people and voters of color that resembled the Obama coalition. But although the precise composition of the 2020 electorate will not be known for months, what is clear is that many national polls underestimated the extent to which Trump’s case for reelection was resonating with voters on the margins of the Democratic base.

Evangelical churchgoers saw every day, on screens and in pews, how the Trump campaign was making its case to millions of evangelical Latino Protestants in Florida and across the country.

“Coming out of the election there is one interpretation: Biden came around too late and didn’t invest the money, and that’s part of the story. But its still doesn’t take seriously the agency or the political agency of Latino Republicans,” said Geraldo Cadava, author of “The Hispanic Republican” and a professor at Northwestern University.

“What we missed was the kind of under-the-radar plotting and relentless pursuit of Latinos,” he said.

Many strategists are reckoning with how the Biden campaign fell short on courting Latino voters.

In the past, there has been an instinct to blame Latinos and to accuse them of not caring enough to vote, said Eric Rodriguez, senior vice president of policy and advocacy for UnidosUS.

This year, Latino voters broke records, increasing turnout by 15 to 20 percent, Rodriguez said, according to preliminary data.

But the increased participation doesn’t favor just one party.

“Our understanding of the Latino electorate has to become much more sophisticated because you can absolutely, as a candidate, knit together a cohesive bloc of Latino votes but you have to understand the segment of voters in a way that neither party does now,” Rodriguez said. “It isn’t the voters’ fault. It’s the campaign’s.”

Meanwhile, the Trump campaign was effective at microtargeting specific subgroups of Latino voters, including evangelical Protestant churches and the Cuban and Venezuelan American communities in Florida.

The vote margins are less surprising to those who have spent time in communities where Trump has seen a surge of support.

There has always been, for example, a significant conservative presence among Latinos in the Rio Grande Valley, where Mexican American families are closely tied to the federal and local law enforcement community. Many of those voters are also deeply influenced by their religious beliefs when it comes to issues such as abortion.

In the run-up to the election, Trump supporters gathered for caravans every weekend of the past two months to parade through the streets of McAllen, Tex., waving flags and signs, honking their horns and celebrating their support.

One of them was Mayra Gutierrez, who moved to the United States from Mexico in the 1980s and became a U.S. citizen last January to be able to cast her vote for Trump.

“We live in the border and we are big on law enforcement here. They need our help,” said Gutierrez, a volunteer for a local Latinos for Trump group. “Yes, this is a blue area but it’s an old blue. The Democratic Party doesn’t stand for what it used to.”

And how does she reckon with Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies?

Gutierrez said she sympathizes with immigrants seeking asylum because of her own immigration story. But the law is the law.

“The money they spend on coyotes and smugglers can pay instead for a legal way,” she said.