The US health system has failed black and Latino populations for decades. Now they’re paying the price.

It has been clear for some time that the coronavirus pandemic is killing black and Latino Americans at disproportionately high rates, but new data from the last few days reveals just how devastating the Covid-19 crisis has been for people of color.

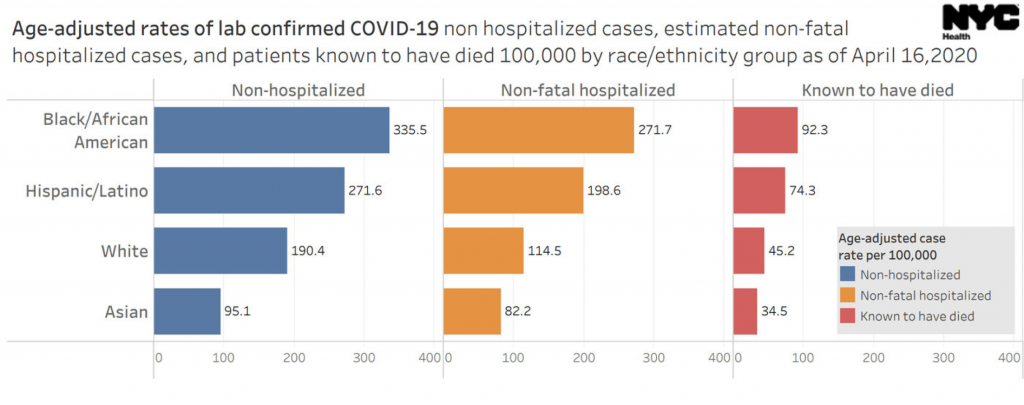

Starting in New York City, the American epicenter of the outbreak: Black New Yorkers are dying at twice the rate of their white peers; Latinos in the city are also succumbing to the virus at a much higher rate than white or Asian New Yorkers. The same trends can be seen in infection and hospitalization rates, too.

Mother Jones compiled data from all of the states that break out their coronavirus data by race and ethnicity. The same thing we’re seeing in New York City is happening across the country: Black and Latino Americans get infected with Covid-19 at alarmingly high rates and more are dying than we would expect based on their share of the population.

A few horrifying examples from the charts you can find in the link above:

In Wisconsin, black people represent 6 percent of the population and nearly 40 percent of Covid-19 fatalities

In Louisiana, black people make up 32 percent of the state’s population but almost 60 percent of fatalities

In Kansas, 6 percent of the population is black and yet black people account for more than 30 percent of the Covid-19 deaths

The proportions can change depending on the state, but the trends are consistent anywhere you look: Compared to their share of the population, greater numbers of people of color die than their white neighbors in this pandemic.

Why is that? Well, there are the more acute reasons (black and Latino people are being put at risk more in their day-to-day lives) and then there are the structural reasons (long-standing economic and health disparities between white people and people of color).

On the first, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority in NYC is a useful and disturbing example. As the New York Times reported last week, bus and subway workers have been hit hard by the coronavirus: 41 dead and more than 6,000 either diagnosed with Covid-19 or self-quarantining because they have symptoms that suggest an infection, as of April 8.

Who works for the MTA? Black people and Latinos. They account for more than 60 percent of the agency’s workforce in New York City, according to estimates from 2016.

Black people in particular are overrepresented in the MTA; they are 46 percent of the city’s transportation workers versus 24 percent of its overall population. (White people, on the other hand, make up 30 percent of local MTA employees but 43 percent of NYC residents.)

This is, again, true across cities and sectors. As Devan Hawkins wrote in the Guardian, black Americans are more likely than white Americans to be employed in the essential services that have been exempted from state stay-at-home orders, and they are more likely to work in health care and in hospitals. In America as in other countries, health care workers make up a disproportionate share of Covid-19 cases.

So the steps states and cities have taken to restrict public activities and slow the spread of the coronavirus, while undoubtedly necessary and productive, have still left people of color more exposed to infection and, ultimately, death during the pandemic.

Those risks are exacerbated by long-standing health inequities in America.

As Fabiola Cineas wrote for Vox last week, black Americans have historically had higher rates of heart disease, diabetes, and high blood pressure than white Americans — all of which make a patient more vulnerable to developing a severe case of Covid-19 and ultimately dying.

I would add that they are also more likely to be uninsured, again for both structural reasons (all the states in the Deep South except for Louisiana have refused to expand Medicaid, which disproportionately hurts black people) and because of the immediate crisis (black people were more likely to lose their job in the recent surge in unemployment). The same is true for Latinos.

And those are the macro trends. All over the country, smaller controversies and policy choices also worsen the health of black Americans and weaken their ability to stay safe during the Covid-19 pandemic. Even something as seemingly simple as clean water to wash hands can be hard to come by for people of color, as this reporting by Khushbu Shah for Vox on Detroit (with 13,000 cases and 1,000 deaths in Wayne County) reveals:

Since 2014, over 140,000 homes in Detroit have had their water service disconnected as part of a debt-payment program, according to records obtained by local news outlet the Bridge. In 2019, more than 23,000 accounts had their water shut off, and 37 percent still hadn’t had service restored as of mid-January. With the virus spreading, the city promised to restore water to residents, but as of March 31, had only done so for 1,050 of the 10,000 people who called with a water service problem (8,000 of those callers did not qualify for the Coronavirus Water Restart Plan, according to a city report).

“They put the onus on the customer to have to go in and take affirmative steps [to restore their water], so there are a lot of people who do not know, or secondly, don’t have the ability to go in and meet with someone,” says veteran civil rights lawyer Alice Jennings, who is working to restore water to the city’s most vulnerable. Her daughter, a Detroit teacher and a cancer survivor, is battling coronavirus.

Community groups, in the meantime, she said, are passing around five gallons of water to residents who don’t have water for drinking, cooking, or bathing, but Jennings doubts that residents are using the scarce water they have to wash their hands. “If the primary recommendation is ‘wash your hands, continuously, wash your hands,’ and there’s no water in the house to wash your hands,” the number of cases is certain to skyrocket, Jennings says.

For decades — centuries, really — America has failed the black and brown people who call it home. Today, as the coronavirus continues to take its toll, they are stuck paying the price for that failure.

This story appears in VoxCare, a newsletter from Vox on the latest twists and turns in America’s health care debate. Sign up to get VoxCare in your inbox along with more health care stats and news.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.