When West Virginia declared a state of emergency to arrest the coronavirus, the social network that aids the homeless froze along with everything else. Charities that offered daily meals and warming stations shut down. Volunteers, many elderly, were too afraid to work in the soup kitchens they usually ran. There was suddenly no place to eat or go to the bathroom. “Our homeless community found themselves being told to stay entirely outdoors,” says Kate Marshall, a charity worker in Wheeling, a city in the state’s northern panhandle. “There was not one indoor place to go from March until fall of 2020.”

Ordered to shelter in place, people without shelter died at an alarming rate. In a bad year here, according to social workers from three charity organizations, two to four of the unhoused die. Over the past year, they have tallied 22 deaths, a sevenfold increase.

Only two of the deaths are suspected to be from COVID-19. But all occurred during the collapse of the safety net that in normal times addresses the complex mix of afflictions—trauma, medical conditions, addiction—that accompany homelessness, and worsened during the profound isolation of the pandemic. “There were days when there were no services at all,” says John Moses, who runs the Winter Freeze Shelter, a refuge of last resort for the three coldest months.

What happened in Wheeling is happening across the country. Even before the pandemic lockdowns that fell hardest on low-income Americans –– and stand to push more people out of their homes –– the Department of Housing and Urban Development reported U.S. homelessness at 580,466 people, up 7% from a year earlier.

Deaths are rising even faster. In San Francisco, the department of public health says deaths tripled over the past year in an unhoused population of 8,035. In Los Angeles, home to a vast homeless population tallied at 41,290, deaths increased by 32%, per the online news organization Capital & Main. Homeless deaths in Washington, D.C., soared by 54%. In New York City, the Coalition for the Homeless reported a death rate up 75%.

The spikes throw the sharpest shadows in smaller places. “We’ve lost a lot of people that, you know, we’ve regarded as part of the family,” says Moses. “What’s important to me is to know them by name.” When the homeless are not anonymous, every death registers as a memory.

Six months before lockdown, Wheeling lost its only hospital with an acute-mental-health facility. Over community protests, Alecto Healthcare Services shuttered the 200-bed Ohio Valley Medical Center, and with it a 30-bed mental-health unit known as Hillcrest. Then nearby Fairmont Regional Medical Center closed. Both had provided drug treatment, plus outpatient services for some 1,600 people. It was a significant loss in a state that had the country’s highest per capita opioid death rate before the pandemic. In the isolation enforced by lockdown, overdose deaths nearly doubled: from 12 in 2019 to 22 in 2020, according to the Wheeling police department.

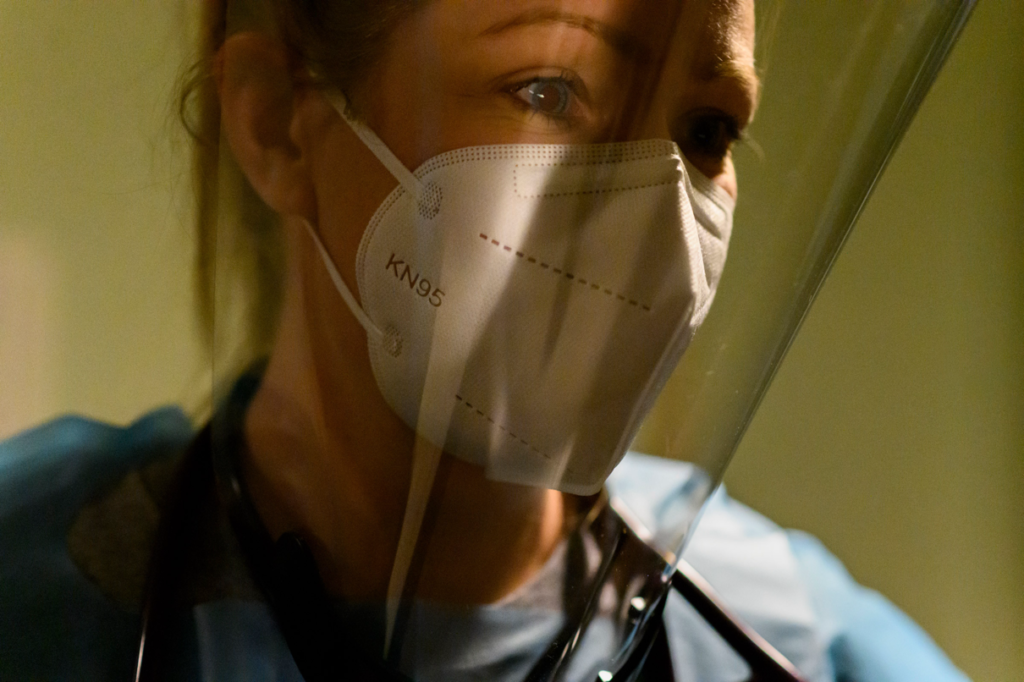

One of those cut off from care was a woman who went by the name Clarice. A young mother, estranged from her family, she was living on the streets while suffering from schizophrenia. “When she was discharged, she was in active psychosis, telling me people were trying to kill her by throwing aspirin on her that she said was burning her skin,” recalls Crystal Bauer, a registered nurse who directs a street medical team for the homeless community.

But Clarice stood out for more than her condition. “When I first met her, we clicked so hard,” says Chrissy Butler, a friend she met on the streets.

“I think anyone on the streets here would say it, that she was a very good friend,” says Marshall. “If she found clothes or makeup in the Free Store, she would share everything. That might seem insignificant, but in this world, it says a lot about her and why people were endeared to her. They could find those moments of clarity within her and connect with that. If she wasn’t that sweet, with her mental-health condition, people would have steered away. But it was the opposite. People watched over her when she wasn’t doing well.”

Clarice’s death distills the tragedy of the past 12 months. Her tent was near the center of the encampment in the woods beside the shuttered hospital. When a neighbor known as Ghost found her body, she had been dead for three days.

The loss shook the community, particularly Bauer. “I don’t care what you’ve done, everyone deserves a dignified end,” says Bauer. Sorting through the tent with Ghost, she found that Clarice had collected tiny bird cages. And when they lifted the tent, under its wood platform lay the body of a robin. “It all just felt unreal,” Bauer says. Three months later, Ghost, a veteran, would be found dead in a tent too.

By October, the police had forcibly removed the camp after an uptick in property- and drug-related crime. Wheeling police chief Shawn Schwertfeger describes Clarice’s death as “a very tragic situation” and “another contributing factor.” Months later, all that remained of the camp were impressions by the tents, branches pressed down like deer beds.

Both Clarice and Ghost died from accidental drug overdoses. “Trauma begets trauma,” says Marshall. “It is not surprising to me that when we’re having a crisis, we revert back to whatever coping mechanisms we know. It’s like taking all the traumas and bringing them to this convergence point of rejection, loneliness, insecurity and no support systems. They lost access to their social workers. Suddenly we were having to say, ‘Yes, your friend just died because they were traumatized and they overdosed. But we’re just going to have to sit here under this bridge.’ It just felt like harm on top of harm.”

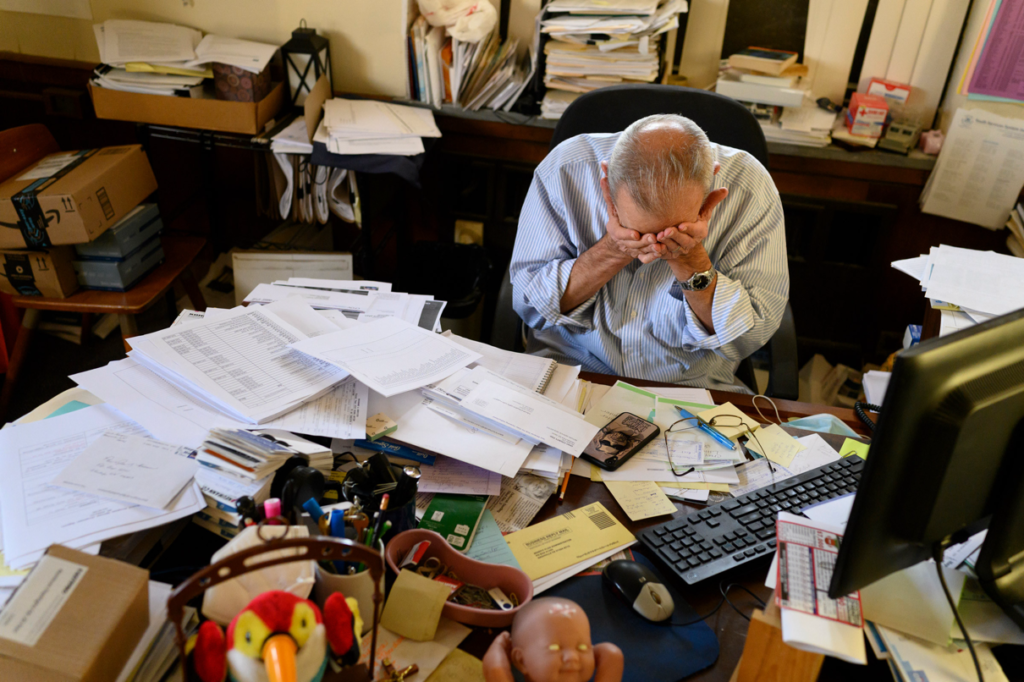

Moses is at the center of Wheeling’s patchwork support network as CEO of Youth Services System (YSS), a nonprofit that provides a number of residential and community-based programs for children and adults. YSS operates recovery houses, a detention center, and mentoring and prevention services. “We never get bored,” says Moses. The charity’s work is deeply entwined with an opioid crisis that, having found its national epicenter in West Virginia, followed an arc: as providers moved from over-the-counter pill mills to dealers peddling heroin and fentanyl, customers moved as well. Some to tents. Some to graves.

“An addict does drugs to get away,” says Butler. “I just want people to see we’re somebody’s daughter, son, mother, cousin or whatever. And they need to understand we are human.” A 2019 survey by the local Coalition for the Homeless found that 96% experienced homelessness as a result of substance-use disorder. And over the past year, they died here at a rate many times higher than the rate of deaths from the virus. “It showed the strength of the opioid crisis,” says Moses. “It surpassed COVID.”

After Clarice’s death, the rest of the year unraveled “like a piece of yarn,” says Butler. “You pull it, and it just comes all unfrayed.” As fall gave way to winter, local photographer Rebecca Kiger spent months documenting the community and efforts to help. With the nearest psychiatric hospital now almost 10 miles away, the empty Ohio Valley Medical Center was pushed into service as the new Winter Freeze Shelter. The available second-floor space had been Hillcrest, the psych ward that a number of the homeless associated with past traumas. Some chose to remain in the cold.

“You know we use that word less,” Moses says. “They’re homeless, they’re penniless, they’re this less. I think we start choking on these abstracts that we assign people that doesn’t explain them.” The kinship between helpers and those they help runs deep here. “Because I have my own stuff,” says Bauer, the RN. “The short version of my story is, I grew up in a home where I experienced every kind of abuse. When I tell people it is a miracle that I am not homeless and living under a bridge, it absolutely is.”

“Every time I write RN after my name, I still can’t believe that I achieved this,” says Bauer, who started nursing school when she was thirty-six. Stemming from her own experiences of having family with addiction, Bauer uses Project Hope to implement preventative Harm Reduction in fighting the opioid crisis. Outreach workers provide clean needles, antiseptics, and condoms to prevent the spread of disease and work as a first step towards connecting with the most distressed drug users, improving health outcomes that often lead to recovery. “This work we do saves the city hundreds of thousands of dollars in medical care, reduces the burden on the local healthcare system, and saves the Virginia taxpayer money.”

“It’s been tragic,” says Susan Brossman a co-founder of Street MOMs. The “Moms” who volunteer take it upon themselves to fill the gaps in services by making themselves available 24/7, giving lifts to appointments and just listening. “Every conversation with these people has to be intentional,” she says, “You have to say what you want to say then because you never know if they’re going to be gone.”

As the Winter Freeze season draws to an end, Brossman worries what will come next after such a deadly year. “I get this visual picture in my mind all the time after church on Wednesday nights,” she says, of the twice-weekly services Street MOMs hosts. “If it’s cold, we’ll drive some of the women up to the Winter Freeze Shelter. On the way back she often sees the men “weighted down,” walking to the shelter. “Oh, it’s tragic,” she says, “I’ve even thought to myself, I need to go another way, so I don’t have to see it.” Her next thought: “I’m like no. You force yourself to see that!”

Arriving at the Freeze for the final night, 32 guests check in the dark lobby of the closed OVMC. Upstairs it’s Taco night. The first young man I meet says “hi” and tells me he’s “autistic” without making direct eye contact. Drug users talk about struggling between detox and addiction. Domestic violence survivors, trans people, developmentally disabled, ex-cons all complain about the barriers to housing. In what Moses calls a “low barrier shelter,” open to all in need, there is only one rule: “You can’t be violent.”

In a community that already felt separate, the coronavirus created yet more distance. Moses’s goal with the emergency shelter is to keep people safe and build connections. “If our intention was to save, rehabilitate and house everyone, we’d all go crazy,” says Moses,” but if you’re staying in the storyline, keep a continuing conversation; that moment may come.”

Toward midnight, a man named Anthony looks for “Mrs. Kate” as she hands out trash bags for people to pack up for tomorrow. He interrupts. “I want to go to rehab,” he says, showing a small abscess forming on his forearm. Marshall pivots to a private room and begins calling around for a bed. This is the kind of interruption she always hopes for.

Everything happening here is related to harm reduction and the connections all this work builds, and in the moments where the work might pay off, speed is essential. Marshall knows the disappointment of someone who, after making the kind of announcement Anthony has just made, begins to feel withdrawal set in and, by morning, has skipped out.

Dawn brings the smell of sausage and biscuits, a special goodbye breakfast. On the flat-screen, a YouTube playlist plays videos; Creedence Clearwater Revival’s Have You Ever Seen the Rain and then Poison’s Something to Believe In. Anthony is showered, happy, and eating a big plate —all good signs. We talk about how many friends he has lost, “feeling numb to everything” on opioids. “I would have given up a long time ago,” he says, and before leaving in a car for rehab, warns me about addiction. “You will lose everything.” A man standing nearby tells me Anthony’s nickname is “The Miracle.”

Time to go. A quiet 55-year-old father named Ron takes his turn assembling donated supplies, then gets a lift to the hillside campsite that will be his home for the next nine months. “I’m kind of embarrassed by the mess,” Ron says, lifting a pink blanket that serves as a door. It opens on two rooms of interconnected tarps willed together with rope and pieces of wood. Clearing piles of clothes and used furniture for us, Ron checks to see if everything is where he left it.

“We’ll sit here and keep a fire going constantly,” he says. “I’m exhausted. I’ve been out here three years off and on.”

When talk turns to the deaths of the past year, Ron says, “I don’t think they intended to end their life like this, you know. We all say we’re going back to normal, but what’s normal? I don’t know how to get there.”

The morning is cold. Everything feels damp. “We have some friends that are missing right now,” he says, “and I’m feeling pretty alone.”

—With reporting by Rebecca Kiger and Julia Zorthian

If you or someone you know may be struggling with addiction, contact SAMHSA and if someone is contemplating suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or text HOME to 741741 to reach the Crisis Text Line.

If you want to help the homeless, visit.