For the first time in decades, a federal court has declared that American public school students have a constitutional right to an adequate education.

The 6th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled last week that the state of Michigan has been so negligent toward the educational needs of Detroit students that children have been “deprived of access to literacy” — the foundational skill that allows Americans to function as citizens — in violation of the 14th Amendment.Promote health. Save lives. Visit who.int

The ruling came in response to a class-action lawsuit filed by a group of Detroit public school students that cited a litany of severe deficiencies: Rodent-infested schools. Unqualified and absentee teachers. Physics classes given only biology textbooks to work with. “Advanced” high school reading groups working at the fourth-grade level.

When “a group of children is relegated to a school system that does not provide even a plausible chance to attain literacy, we hold that the Constitution provides them with a remedy,” wrote Judge Eric L. Clay for a 2-1 majority.

The overwhelming majority of students in the Detroit public schools are black or Hispanic and come from low-income families. Clay noted that through the nation’s history, white people have repeatedly withheld education in order to deny political power to African Americans and others, most notably under slavery and segregation.

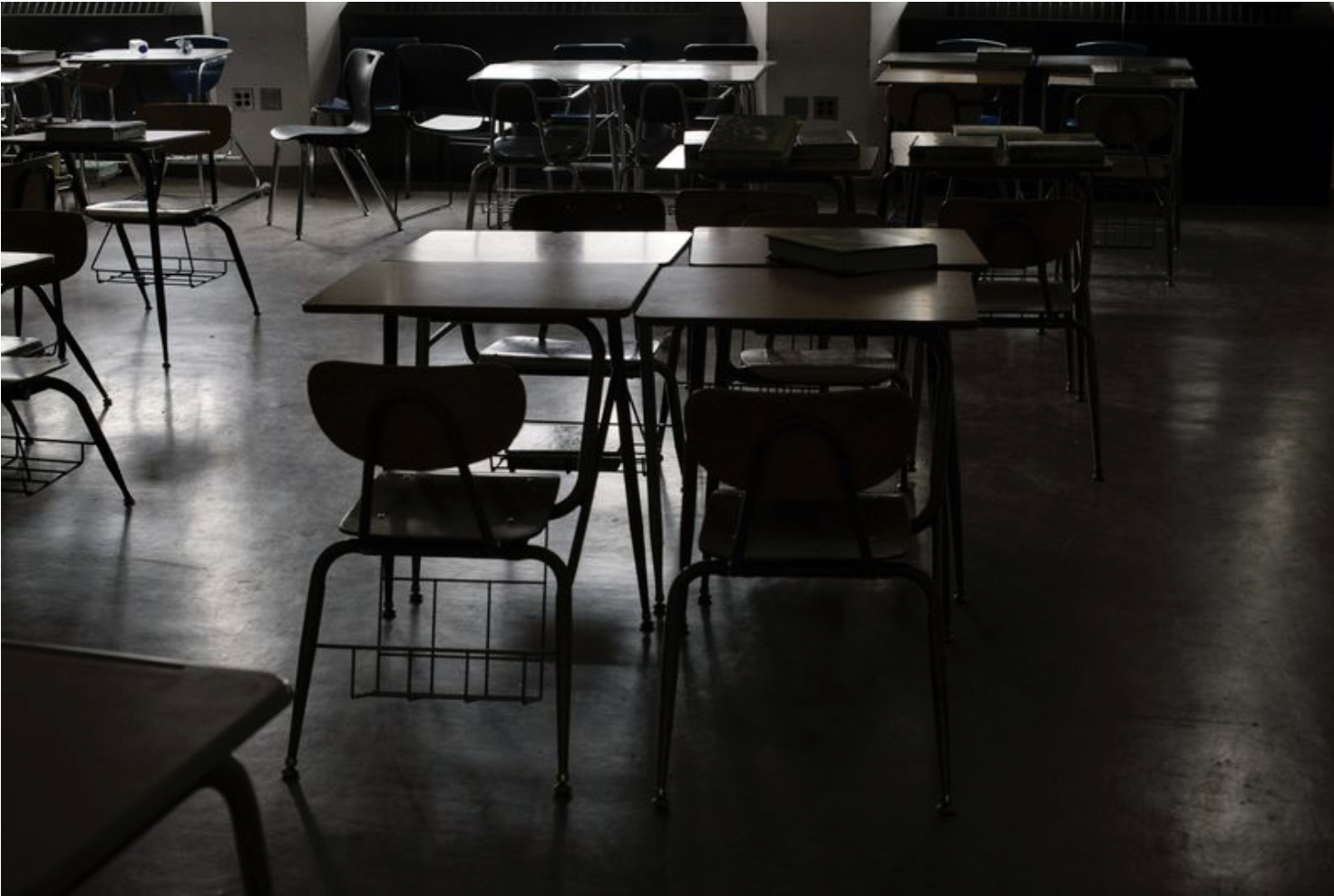

Detroit, an epicenter of coronavirus transmission, has closed its schools because of the pandemic and may not be able to reopen them for months, a situation that is expected to worsen inequities and have a negative effect on students’ learning for years to come.Promote health. Save lives. Visit who.int

Jamarria Hall, 20, one of the plaintiffs, said the ruling confirmed what he had always suspected about his Detroit public high school — that it did not provide students with a good education. Although he graduated at the top of his high school class, Hall struggled at the community college he attended and was put on academic probation. He is now working with a tutor to improve his skills.

He wants the next generation of Detroit children “to have a chance,” he said. “This is our future. These are our voters.”

The case, known as Gary B. v. Whitmer, is one of a group of lawsuits arguing that conditions such as segregation and unequal per-pupil funding violate children’s rights. Some of the cases, including the Detroit lawsuit, challenge a 47-year-old Supreme Court ruling that equality in education is not constitutionally guaranteed.

It is not yet clear what remedies will be considered in the Detroit case. In February, another lawsuit over the right to literacy, brought in California state court, led to a relatively modest settlement of $53 million, which the state will distribute to 75 low-performing elementary schools. And now, with the devastating economic effect of the pandemic, it may be hard to find much new money for public education.

Like the California settlement, the Detroit ruling did not wade into a major debate within the education world about which methods are most effective in teaching children to read.

The complaint in the case calls for “evidence-based literacy instruction” with a foundation of early-childhood phonics — explicit lessons on the relationship between letters and sounds. But the ruling did not mention the research on how children learn to read. The 6th Circuit sent the case back to a district court to address the students’ claims.

Tacy F. Flint, one of the plaintiffs’ lawyers and a partner at the firm Sidley Austin, suggested in an interview that Detroit schools had more basic problems to solve before turning to debates over literacy strategies.

“If that was a debate that we were having in these schools, that would be fantastic,” she said. “But we’re not remotely there. Getting a teacher in the classroom is the first step, having books and having adequate physical facilities.”

Though the evidence of inadequacies amassed in the four-year-old lawsuit is damning, students in the Detroit Public Schools Community District have shown some recent improvements in reading. The district has adopted a new curriculum and more rigorous phonics coaching for students who struggle to read.

There has also been an emphasis on assigning students more difficult texts. Previously, pressure to raise standardized test scores resulted in too much focus on helping children answer multiple choice questions about short, simple passages, Nikolai Vitti, the district superintendent, said in an interview late last year.

After the changes, “students are actually reading books and novels again,” Vitti said.

The ruling in Gary B. v. Whitmer was announced on the same day that the school system said it would work with local philanthropists to distribute free tablet computers and provide six months of internet service at no cost to 50,000 students who are attending classes remotely because the schools are closed.

When the lawsuit was originally filed in 2016, Rick Snyder, a Republican, was governor of Michigan, and he was the named defendant. His successor, Gretchen Whitmer, is a Democrat, and she has not said whether she will appeal the ruling.

A spokesman for Whitmer said on Sunday that her office was reviewing the court’s decision. “The governor has a strong record on education and has always believed we have a responsibility to teach every child to read,” he said.

The ruling was issued by a three-judge panel of the 6th Circuit, with one judge, Stephen J. Murphy III, dissenting. It could still be taken up and reversed by the entire 6th Circuit, if the court’s other judges find the dissent compelling.

“If I sat in the state legislature or on the local school board, I would work diligently to investigate and remedy the serious problems that the plaintiffs assert,” Murphy wrote. “But I do not serve in those roles. And I see nothing in the complaint that gives federal judges the power to oversee Detroit’s schools in the name of the United States Constitution.”

The case could be appealed to the Supreme Court, whose conservatives have not been friendly to educational equality claims.

In recent years, though, concern about Americans’ lack of preparation for citizenship — a key part of the 6th Circuit’s ruling — has widened across the ideological spectrum.

In his 2019 year-end report on the federal judiciary, Chief Justice John Roberts lamented that “civic education has fallen by the wayside,” and added: “In our age, when social media can instantly spread rumor and false information on a grand scale, the public’s need to understand our government, and the protections it provides, is ever more vital.”

Justin Driver, a professor at Yale Law School and an expert on education and the Supreme Court, said it was “not at all obvious” that judges appointed by Republicans and Democrats should disagree on “whether American children have a basic right to literacy.”

c.2020 The New York Times Company