Built at the turn of the seventh century, the white plaster-coated road begins in Cobá and ends 62 miles west, at Yaxuná’s ancient downtown in the center of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. Courtesy of Traci Ardren and Dominique Meyer / University of Miami

Dubbed the “white road” in honor of its limestone paving, the 62-mile path is an engineering marvel on par with Maya pyramids

When Lady K’awiil Ajaw, warrior queen of the Maya city of Cobá, needed to show her strength against the growing power of Chichen Itza, she took decisive action, building the then-longest road in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula and pav her army to counter the enemy’s influence by seizing the distant city of Yaxuná—or so a new analysis published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reportssuggests.

The study, led by researchers from the University of Miami and the Proyecto de Interaccion del Centro de Yucatan (PIPCY), shows that the 62-mile path is not a straight line as previously assumed, but a winding path that swerves through several smaller settlements. Because the road was raised, the researchers were able to spot it using LiDAR (light detection and ranging) technology, which measures the texture of a landscape based on how long it takes light to reflect back—like echolocation, but with lasers. Built around 700 A.D., the sacbe, or “white road,” derived its name from a limestone plaster paving that, thanks to the reflection of ambient light, would have been visible even at night.

“We tend to interpret [such projects] as activities which sort of proclaim the power of one polity, or at least, the alliance of some nature between the two polities,” university of Miami archaeologist Traci Ardren tells Live Science’s Tom Metcalfe.

By conquering Yaxuná, K’awiil Ajaw may have been trying to establish clear, strong ownership at the center of the peninsula. Adds Ardren, “Cobá represents a very traditional classic Mayan city in the form of a dynastic family, which holds all the power and is centered on one place.”

When archaeologists armed with basic tools like a measuring tape and compass first unearthed the 26-foot-wide road during the 1930s, they thought it was perfectly straight. But the new LiDAR imaging has complicated that perception, revealing that the road curves to pass through smaller neighboring Maya settlements. Rather than constructing a road used solely for conquest, K’awiil Ajaw appears to have made time for stops along the way.

“This road was not just connecting Cobá and Yaxuná,” says Ardren in a statement. “[I]t connected thousands of people who lived in the intermediary region.”

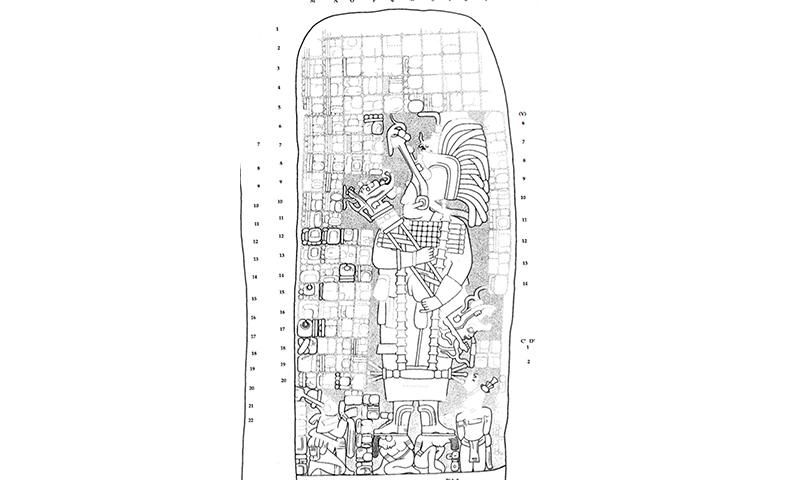

Previous researchers have found evidence that the queen of Cobá set out on numerous wars of territorial expansion. Travis Stanton, study co-author and an archaeologist at the University of California, Riverside, tells the Yucatan Times of “bellicose” statues and monuments that depict her standing over unlucky captives. Still, Stanton says to Live Science, the archaeologists have yet to identify concrete evidence pointing to who built the road or how long it took to construct.

Chichen Itza’s more “plugged in” economic and political system differed from Cobá’s traditional, conquest-driven kingdom, according to Ardren.

Per Live Science, researchers have found evidence pointing to Chichen Itza’s connections with distant regions of Mesoamerica, including Costa Rica and the American Southwest. The famous Maya city and Unesco World Heritage Site is known for its stepped pyramids; it grew in strength during the centuries after K’awiil Ajaw’s reign.

This summer, the team plans to complete a dig at the site of a settlement identified by the new LiDAR scans. If the group’s hypothesis regarding K’awiil Ajaw proves correct, then artifacts found in the settlements between Cobá and Yaxuná will show “increasing similarities to Cobá’s” over time.

In the statement, Ardren calls the massive road an engineering marvel on par with Maya pyramids. Paved over uneven ground that had to be cleared of boulders and vegetation, it was covered in white plaster made with a recipe similar to Roman concrete.

“All the jungle we see today wasn’t there in the past because the Maya cleared these areas” to build homes and burn limestone, says Ardren in the statement.

She adds, “It would have been a beacon through the dense green of cornfields and fruit trees.”

Recommended Videos

SmartNews: Maya Beheadings

Dismembered war captives from the 17th century uneartherd