Many things led to the events of Sept. 29, 1969.

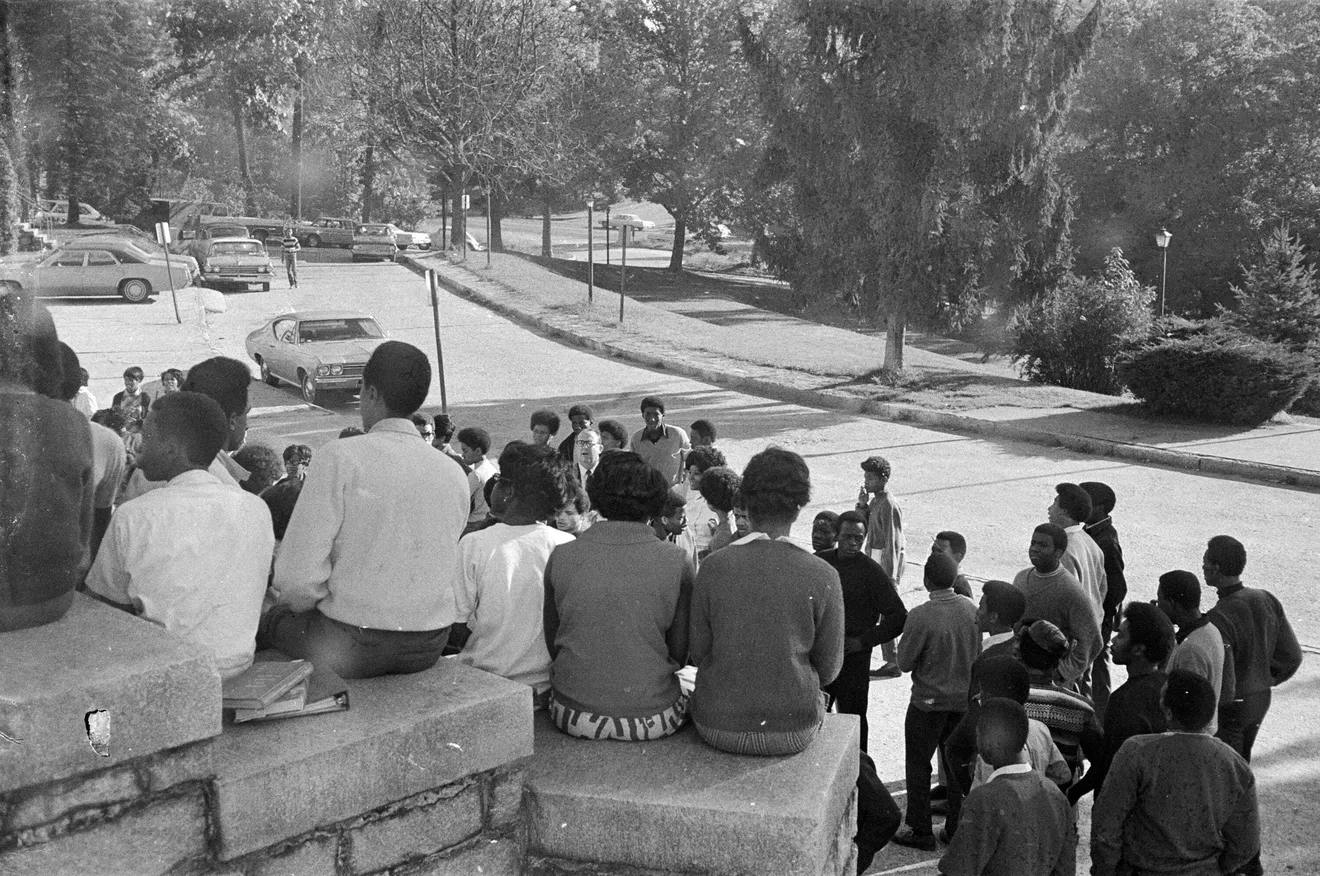

Ignored requests, denial of rights and silenced voices were among the catalysts for the famous Asheville High School walkout when nearly 200 Black students picked up their books and calmly walked to the school’s front stairs. They planned to stay there until school administrators agreed to meet with them.

They figured they had that right since the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution guarantees Americans the right to peaceably assemble, though Black Americans in the 1960s often were starved of that right. From Selma to Little Rock, they were met with violence and contention when they asserted the rights contracted to them by the bedrock of the United States government.

The quiet mountain city of Asheville was no exception.

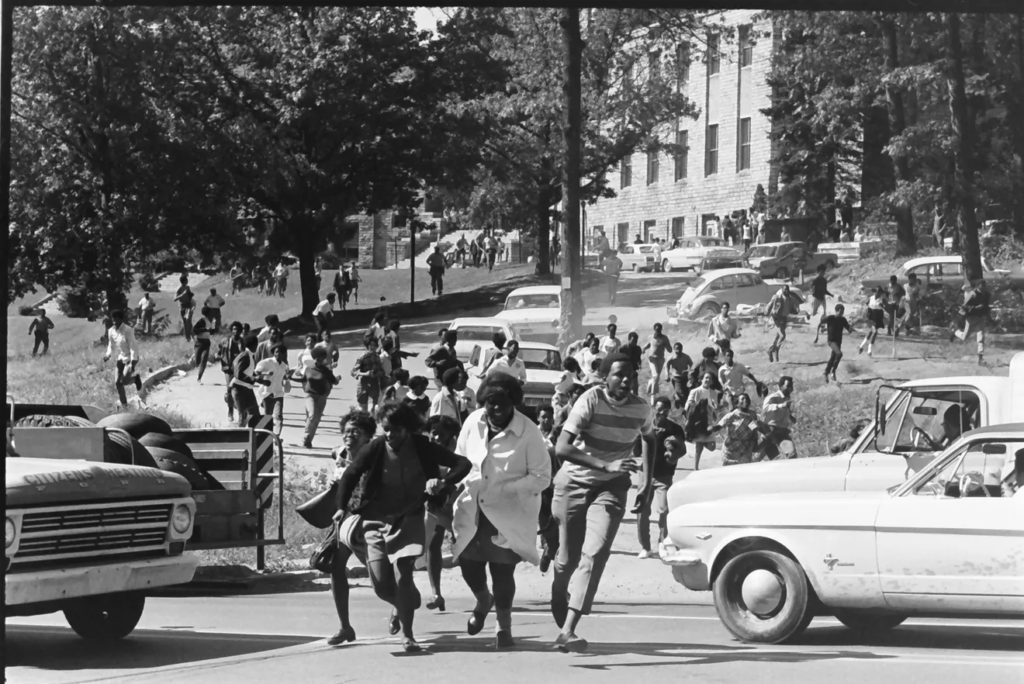

What transpired after the Sept. 29, 1969 nonviolent AHS walkout, according to news reports, was aggression that led to six students and five policemen being treated at Memorial Mission Hospital, overturned cars and broken glass, a shaken student body and the unwarranted expulsion of one of the walkout’s organizers.

Black students’ requests that led to the walkout were simple — they wanted to be acknowledged and represented.

The walkout

According to 1969 coverage by the Citizen Times, Black students created a list of grievances they wanted addressed by Asheville High. Among those requests were for Black students to no longer be called “colored” or “boy,” fair punishment for Black students and athletes and a Black educator to teach Black history and cosmetology — or at least include in the curriculum how to style Black hair.

“I remember that one of the things we wanted also was some of the teachers from our Black schools to be integrated into the teaching staff at Asheville High, and that was one of the grievances they wouldn’t do,” Leo Gaines, the expelled student, said in 2014.

Gaines was unavailable for a Citizen Times interview. He did, however, speak extensively about his experience with a fellow Asheville High student at the time of the walkout, Dan Lewis.

Lewis has made uncovering the true events of Sept. 29, 1969, his mission for several decades. He created a Facebook page with newspaper excerpts, discussion by former AHS students and transcribed interviews with walkout participants such as Gaines. Quotations from Gaines used in this article have been provided to the Citizen Times by Lewis.

While in school, Gaines was outspoken about the needs of Black students at the newly integrated Asheville High School. The walkout, which occurred just after Asheville City Schools was desegregated, largely was rooted in the students’ desire for their experience at Black schools like Stephens-Lee and South French Broad high schools to be blended into their schooling at Asheville High.

Gaines spoke about these desires in public and private meetings, and because of this, he had gained notoriety among the majority white school board and administration.

“I guess my speech was kind of radical — not shaking my fist or shouting but very assertive — and would argue my point until the cows came home,” Gaines said.

“I spoke about change and the fact that change had to happen now because everybody wanted to kick the can down the road. (They said) ‘We’ll do this. You’ve just got to give it time, and then people will change’ and I was of the mindset that ‘No, change has to happen now. We don’t wait. We waited for 200 years. Change has to happen now.’”

To bring about that change, students organized the peaceful walkout. It was set for 9 a.m.

The roughly 200 students made their way to the stairs. One student began reading the list of grievances. AHS Principal Clark Pennell asked the students to go back to class. They refused.

Police ‘acting like stormtroopers’ and a curfew

Gaines said after about 15 minutes, police came out of the school “acting like stormtroopers” forcing the protestors off-campus. The police had entered the school through the back door.

“They were angry. You could see it in their faces,” Gaines said. “They were all white. They didn’t allow the Black policemen to participate in it. The policemen were very angry, and when they were poking at you, they weren’t pulling any punches. They were poking you, forcing you to move. The people on the front were getting pretty beat up.”

The police continued to push the students off the school’s property.

“We had control of the situation until they charged us, and after they charged us, it became a melee,” Gaines said. “Some of the kids started picking up rocks and throwing at them because that was the only defense you had other than out-running them.”

After the students were forced off campus, school was dismissed early. A curfew went into effect throughout all of Asheville for three days.

“The curfew makes it unlawful for any person not specifically exempted to be on public streets or property, or to operate businesses or places of entertainment or public assembly from 9 p.m. to 6 a.m.,” the Citizen Times reported Sept. 30, 1969.

“Exempted are law-enforcement officers, public and utility employees, medical and other health personnel and members of the news media (newspapers, radio and television).”

Working on grievances, but at a cost

Eventually, Asheville High School’s administration heeded the Black students’ pleas — agreeing to a meeting and ultimately working on the grievances.

But there was a caveat. Gaines, the outspoken leader who had been flagged by the administration, had to be expelled.

“It was sort of surreal. I was taken aback by the whole thing because, in my mind, I had not expected anything like (the riot) happening. I expected us to go out, sit on the steps for a few hours, and then everybody go home,” Gaines said, who had just started the 11th grade. “I was just sixteen years old, so I was totally stunned and did not know what to do at that point, so I was just stunned. Fearful would be a good word, because I started getting death threats at my house.”

Following his expulsion, Gaines took a year off of school and stayed in hiding before attending Asheville Catholic School. He went on to receive a bachelor’s degree from Shaw University and worked as a counselor at the Juvenile Evaluation Center in Swannanoa. He got married and had one daughter, who now works in Asheville City Schools.

While Gaines’ life fared well, he said he always felt a “little angry” — mostly because, with his high school career being interrupted, he was unable to study what he had always wanted to in college: astronomy.

Reparations too late in coming?

Now, 52 years later, some say there’s a way to vindicate not only Gaines’ anger but his wrongful expulsion altogether.

In July 2020, Asheville passed its reparations, apologizing for the city’s role in slavery, discrimination and denial of basic liberties to Black residents and directing the city manager to gather recommendations addressing the creation of generational wealth, economic mobility and opportunity in the Black community.

More on reparations:Asheville recognizes Juneteenth, commits $2.1M for reparations

Last week, the conversation arose that perhaps Gaines should be considered in the city’s reparations — receiving a diploma from Asheville High School more than five decades after his expulsion.

The suggestion came during the Q&A portion of the city’s June 3 Truth Telling speaker series — panels to discuss the city’s reparations plans.

“This would be an amazing thing to try and get some kind of recognition,” Lewis said. “We’re not taking about reparation on a level of anything that costs anything other than the admission that an administration, long before the present, made a serious mistake.”

Asheville Mayor Esther Manheimer said she thought giving Gaines his AHS diploma was a “wonderful idea.”

“Ultimately this is something that falls under the school board’s jurisdiction, but I am glad to work with them to coordinate the effort to acknowledge and apologize for the suffering experienced by Black students during the period of desegregation,” she said.

Asheville City Board of Education Chair James Carter said he is researching more about the school board’s role in Gaines’ potential reparations.

“Personally, I am not opposed to this idea,” he said. “Please note that this is my personal opinion, and that I am not speaking for the board or the system as a whole.”

Reparations may come, but some may come too late. On June 10, Gaines died of pancreatic cancer.

“In the end he was at peace and not in pain,” his wife Brindia Arrington Gaines wrote on Facebook.

Though Gaines won’t see his AHS diploma should the reparations be approved, he said he did see headway in the world of racial equality.

“After all this happened, then there were a lot of people and groups that wanted to get together and talk about race,” he said. “Sometimes, change only happens when it’s forced on people. We don’t make history. History happens around us, and we don’t recognize it until years afterwards.”

A memorial service for Gaines will be held at 2 p.m. June 26 in the chapel of Groce Funeral Home at Lake Julian.