Transitional justice has worked for dozens of countries with a legacy of systemic abuses.

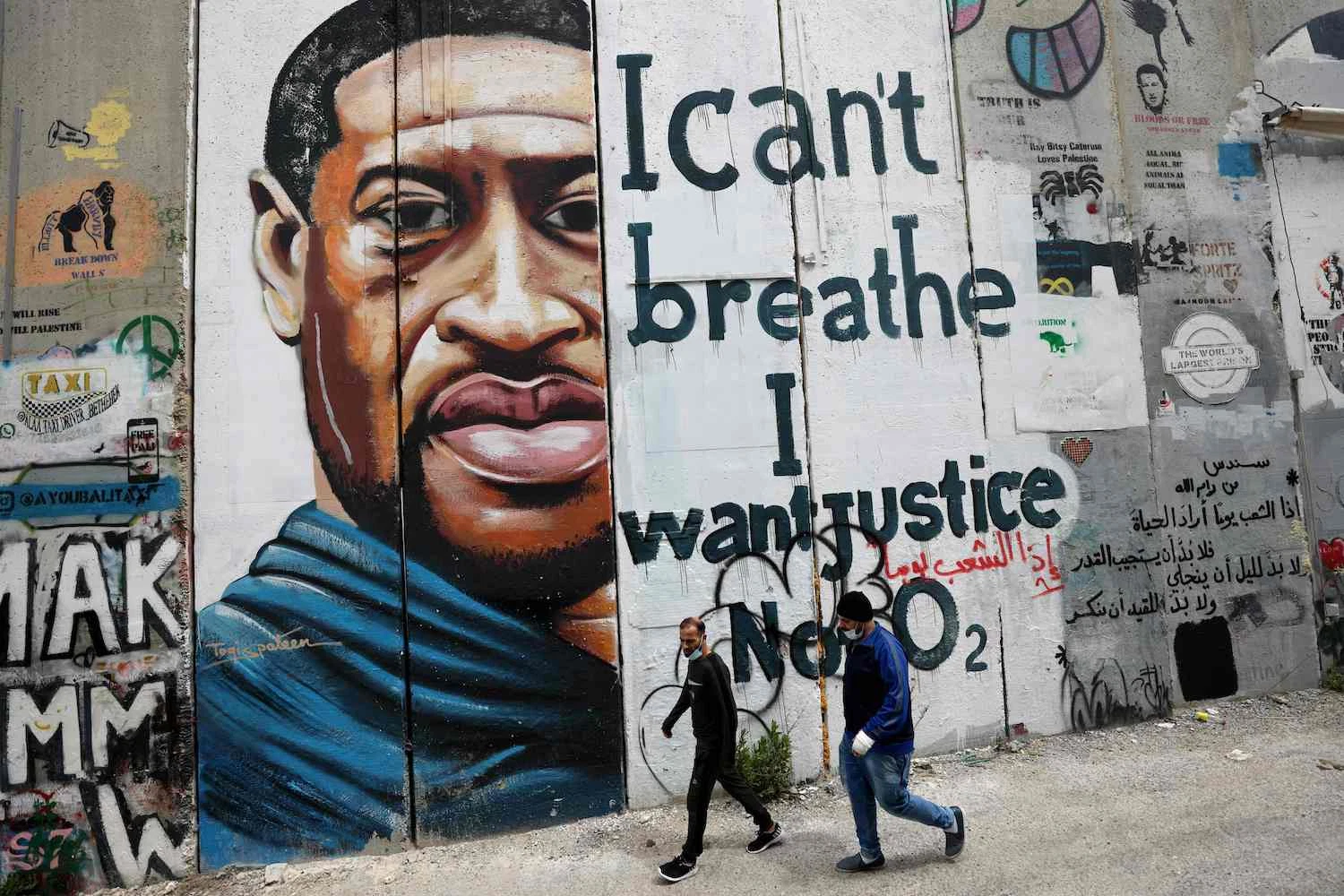

Last week, almost a year after George Floyd’s death first sparked a global reckoning over racial injustice and police violence, Derek Chauvin was convicted of second-degree murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter.

While the verdict brought widespread relief, the decision—which was punctuated by other police killings—also raised questions about whether justice was actually served. Just 30 minutes before Chauvin’s conviction, Ma’Khia Bryant, a 16-year-old girl, was killed by an officer in Ohio. On April 11, Daunte Wright was fatally shot during a traffic stop only 10 miles from where Chauvin was on trial. And in late March, 13-year-old Adam Toledo was killed by police in Chicago.

In recent weeks, there have been increasing calls for action that goes beyond the U.S. criminal justice system. “Truth commissions, and transitional justice more broadly, are long overdue in the United States,” the political scientist Kelebogile Zvobgo wrote in Foreign Policy in response to Chauvin’s conviction. But what exactly is transitional justice—and what could it look like in the United States?

What is transitional justice?

The term is broadly used to refer to measures, both judicial and nonjudicial, meant to remedy systemic human rights abuses and widespread, sustained violence.

“Transitional justice is the process of dealing with widespread wrongdoing,” said Colleen Murphy, a professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “So it’s not interested in [or] doesn’t focus on sort of isolated criminal acts but is relevant when there’s patterns of wrongdoing—and often, the wrongdoing that is of interest characteristically implicates state actors.”

Right now, in the United States and many other countries, the standard recourse is the criminal justice system, which doles out prison terms or fines for specific individuals in response to specific crimes. But this process “doesn’t transform societies. It doesn’t help us to achieve ‘never again,’” Zvobgo said.

In contrast, “transitional justice is really a generational project, a sort of committed undertaking to try and change how we interact in our community,” Murphy said. But there are still limitations to what it can do; since these are usually government programs, expectations of what they can accomplish must be realistic.

“[A complete transformation] is not something that a single truth commission can achieve or a single process of security sector reform or program of reparations,” Murphy said.

In practice, what does that actually look like?

Zvobgo talks of a “transitional justice toolkit,” or a collection of instruments that governments can use to redress past violence and safeguard against future abuses. The toolkit can include a number of measures—truth and reconciliation commissions, memorials, reparations, institutional reforms, prosecution, and commemoration—that can address historical injustices.

Together, these tools are “mutually constitutive and mutually reinforcing,” Zvobgo said. “If you determine or ascertain a particular truth, then what do you do with them?” In some cases, she said, that will mean criminal prosecutions. In others, reparations for survivors or the families of victims. More broadly, she said, structural reforms can “prevent the abuse that you’ve documented … from happening again.”

Where has this been done before?

All around the world. If the United States went down this path, it would be following in the footsteps of countries like South Africa, Colombia, and Germany that have turned to transitional justice to grapple with painful legacies. In the past few decades, more than 40 truth commissions have been established across the globe.

“You see transitional justice being pursued on every continent on the globe, from Cambodia dealing with the legacy of the Khmer Rouge to Europe dealing with the aftermath of Nazi Germany in the Holocaust and the fall of communist regimes in Eastern Europe to Latin America,” Murphy said.

In post-genocide Rwanda, for example, the government established more than 12,000 community-based courts, a combination of local conflict resolution practices and punitive legal measures, in pursuing transitional justice. In South Africa, a truth and reconciliation commission grappled with the country’s long legacy of apartheid. And in Guatemala, the country’s Historical Clarification Commission released a report concluding that genocide was perpetrated against the Mayan people. “Being able to put words to reality and meaning to those words was incredibly powerful for communities, especially the Maya population that was the primary target of violence,” Zvobgo said.

What would this look like in the United States?

The United States has yet to fully embrace transitional justice on a federal level, but these kinds of measures aren’t entirely new, either. In some states, certain transitional justice measures have already been—or are in the process of being—adopted.

Maryland, for instance, has established a Lynching Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate and bring justice to those impacted by racial lynchings. And in March, Evanston, Illinois, approved reparations for eligible Black residents that suffered under discriminatory housing policies between 1919 and 1969.

Nationally, strides have also been made in this direction. In June 2020, Rep. Barbara Lee introduced a bill to establish a Commission on Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation. The bill is meant to help “understand [the] racial discrimination imbalance in this country … [and] actually establish that throughline that threads and helps to explain how what happened then affects us today,” Zvobgo said.

But since places have different historical legacies, there is no one-size-fits-all recipe. The specifics of transitional justice depend on the place—and context.

“You need initiatives like you’re seeing at the city level, at the state level, because the history of places is not identical. … What redlining looked like in Evanston is not the same as it looked like in other places,” Murphy said.

Is now the best time to do this, at a time of intense political polarization?

“I’m optimistic about the present moment, just because there’s so much happening in different places by way of transitional justice efforts,” Murphy said, while noting that transitional justice is always deeply contested. Deep polarization hasn’t stopped other countries from undertaking these efforts. “It’s a promising context for saying, OK, let’s try and do this.’”

This is not to say that it will be easy. “There’s still ongoing denial about how wrong our past was,” said Murphy, who pointed to Sen. Tom Cotton’s remarks that slavery was a “necessary evil.” “Instead of just categorically condemning that aspect of our history, to try and rationalize it—that’s an impediment to getting transformative change.”

But even with these challenges, confronting the past is necessary for transitional justice to work.

“You don’t actually get real unity, you don’t actually get real healing, until you first acknowledge the past,” Murphy said.