Donated to the poor by a eunuch official to the caliph, who couldn’t leave it to heirs, the endowment should have been eternal – but then the Crusaders arrived

The earliest known complete waqfiyya inscription in the Islamic world, which came to light (again) when it was auctioned at Christie’s in 2015, has now been deciphered. Engraved on a soft limestone, the waqf involves the endowment of two farmsteads in ninth-century Palestine, complete with quality animals necessary to work the land. The property was made over to the poor, in the name of Allah, likely by a high-ranking eunuch in service of the caliph.

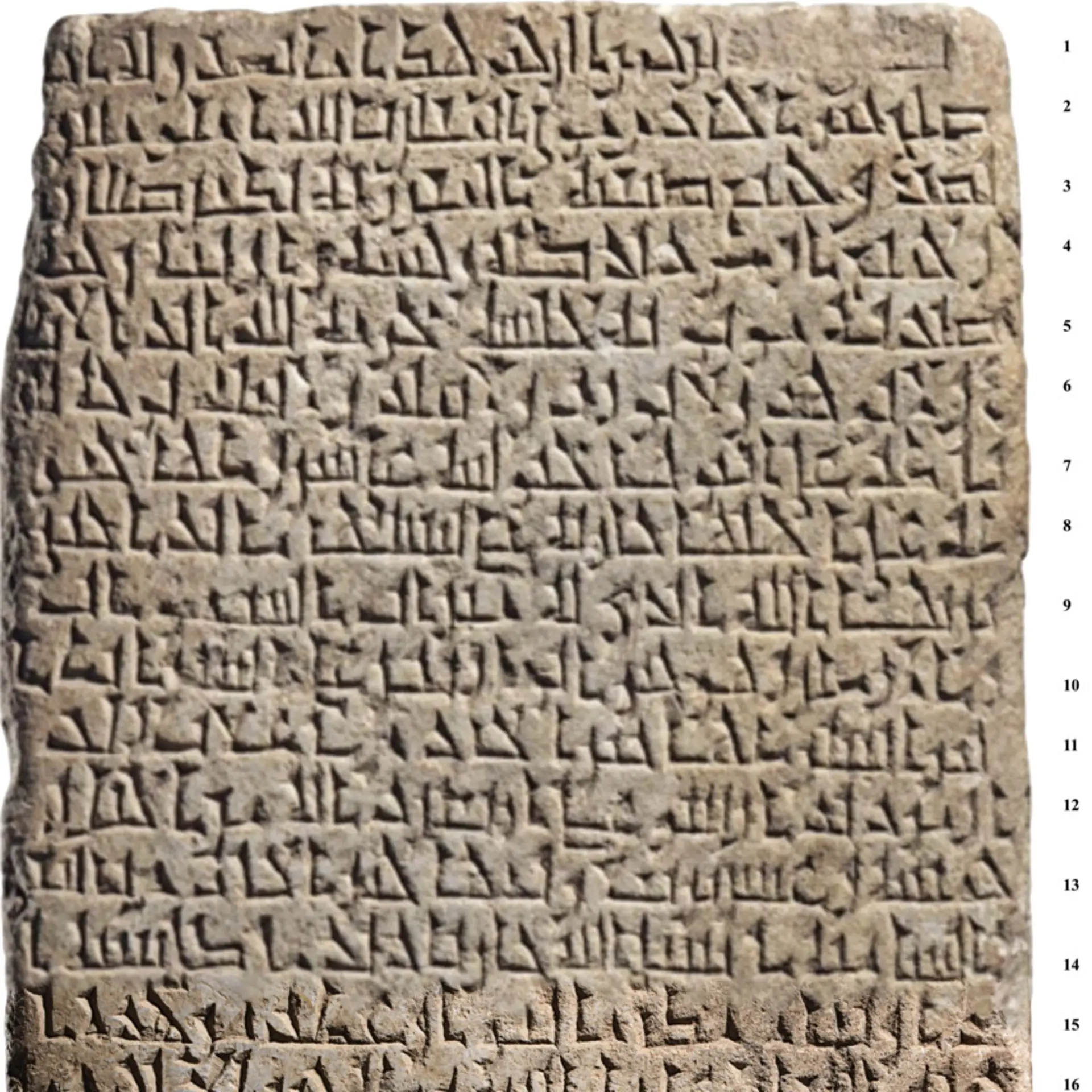

Engraved in kufic script, the stele was deciphered by Prof. Lotfi Abdeljaouad, an Arabic epigraphy expert at the National Heritage Institute in Tunis, at the behest of Prof. Mehmet Tütüncü, the director of the Turkish and Arabic World Research Center in the Netherlands and editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Turkology – who learned about its existence from Christie’s auction catalog.

A waqfiyya inscription is an irrevocable document of endowment of property to Allah for the good of the people. Abdeljaouad’s interpretation was published in December in the International Journal of Turkology.

The stele would have been publicly displayed, Abdeljaouad explains, adding that likely two existed: one at the entrance to each farmstead.

Altogether, Abdeljaouad lists seven ancient stone waqf inscriptions discovered to date – four in Palestine and three in Saudi Arabia – though some were subsequently lost. Wondrously, the newly deciphered stele seems to bear a relationship with another one dating to just a decade or two later: the Ramla inscription, which was publicized in 1966.

Abdeljaouad’s paper is based on photographs of the stele publicized by Christie’s, he explains. The auction house had defined it as “a large and impressive calligraphic marble stele,” 118.7 centimeters in height (nearly 47 inches) and 54 centimeters wide, hailing from the Near East or Egypt and dating to about 880-900.

To be sure, this waqfiyya isn’t the earliest such document. However, it is the oldest complete one, despite some erosion at the edges, Abdeljaouad points out, adding that a few letters are gone. But all 32 lines are there.

“There are some very fragmentary mentions of waqfs from early Islamic times, but no waqf deeds and acts have been preserved,” Tütüncü explains. “This is the earliest text that has come to us that is complete and perfect with a full description of waqf rules,” he adds.

Asked whether such inscriptions come up for auction, Christie’s said that while it cannot comment on all items ever sold at Christie’s, “we do not recall a similar waqf inscription.”

The scholars draw attention to similarities between the two inscriptions: the one they sold “relates very closely” to the Ramla inscription.

That one was reported in the Journal of Arabia in 1966 – and at the time was deemed the earliest known, dating to 913-914 C.E. (the early 10th century). It actually has a date carved onto it.

The newly described one is too cramped for space (possibly) to bear a date too but is believed to be earlier, from the year 866 or a little later – but the late ninth century, in any case.

“The style of the kufic calligraphy on our stele with the distinctive large angular letter ha is matched in style by the dated Ramla tablet as well as another undated fragment of a waqf inscription carved in stone found in the same location,” Christie’s says in its information on the stele; Abdeljaouad also notes similarity to writing found in Jerusalem.

Moreover, the names of the donors on the Ramla tablet and the newly reported stele seem to be related, according to Christie’s: “The donor of our stele is a certain Abu Salih Khayr al-Khadim and that of the Ramla tablet a certain Fa’iq al-Khadim.”

The “al-Khadim” title of both benefactors identifies them as high-placed eunuchs, according to the scholars and reiterated by Christie’s. The donor is described as “mawla,” or a client, of the Abbasid Caliph al-Mu’tazz b’illah, who reigned for just three years from the year 866 to 869.

“They had to have been eunuchs,” Tütüncü says – people positioned near the caliph, who had direct access to the private rooms (harem). “Because they were so near the caliph, they had access to state properties and were allowed by the sultan to gather riches and properties. But because they had no children and heirs, their riches were later expropriated by the state.”

Rather than suffer that postmortem indignity, for the sake of their well-being in the afterlife they tended to donate their fortunes or transfer it into a waqf. And that is why, Tütüncü concludes, the richest waqfs from this period were made by eunuchs.

Indeed, the donor named in the slightly later Ramla tablet is described as a “client” of the next caliph, al-Mu’tamid ‘ala Allah, who reigned from 870 to 892 – which ostensibly seems odd, if the stele dates to the year 913.

Christie’s explains that the late ninth century was a particularly turbulent period at the Abbasid court, with several short-lived rulers; relations between the Tulunid dynasty regnant in the Levant and Egypt and the Abbasid caliphs in Baghdad were terrible. “It is therefore not surprising that the date of the Ramla tablet does not actually match the regnal dates of the caliph under whose jurisdiction it asserts it was composed,” the auction house says.

Long story short, there were apparently some rulers who did not recognize other rulers; there must be some doubt about which stele is earlier. However, the auction house suggests relating to the stele it sold as the earlier one: the similar calligraphy of the two steles suggests proximity in time; and, logically, “our stele should predate the Ramla tablet as it carries the name of an earlier caliph (al-Mu’tazz),” it sums up.

Supporting the tentative dating of the newly described stele, Christie’s notes that the kufic letters are more cuneiform-like and angular than in 10th-century inscriptions from the same region, which are more rounded.

“This contrast is evident when examining the letter mim on a marble foundation tablet in the Louvre which was found in Ashkelon and is dated to the 10th century,” the auction house says – that artefact is described in Pierres et etucs epigraphies (“Stones and epigraphies”).

Generous in medieval Palestine

The story of the steles sheds light on the turbulence of the early Islamic period and, all this said, the provenance of the newly interpreted stele is unclear. Its original discovery is not on record. The seller was a private collection in Switzerland, Tütüncü says; Christie’s declined to elaborate, on the grounds of client confidentiality, ditto regarding the buyer. How the stele with the writing reached the Swiss collection is unknown.

But while the provenance of the stone stele is mysterious, Abdeljaouad is confident that it’s genuine: “The form and writing of this inscription, similar to those of the late third and early fourth centuries of the Hegira (ninth-10th centuries A.D.), give it an unquestionable authenticity,” he writes.

Another enigma is that according to the auction catalog, the stele was classified as hailing from Baghdad, Tütüncü says – but it refers to villages in Palestine.

Christie’s did share that the stele changed hands for 80,500 English pounds, which was within the ballpark of its expectations and is, according to today’s exchange rate, around $105,000 – “not very expensive, even cheap” for such a unique item, in Tütüncü’s opinion.

Despite being an expert in epigraphy and inscriptions, and having written two books on Islamic inscriptions in Palestine, and an article, he for one couldn’t read it, he says.

“It was written in a very strange format, a cuneiform-like Arabic script. Nobody could read it,” he explains. He contacted Abdeljaouad, an expert on ancient Arabic Kufic inscriptions, and, Tütüncü reveals, the process of deciphering the writing took nearly two months.

Abdeljaouad points out in his paper that the inscription is rife with orthographical errors and that some of its letters were carved in irregular fashion, rendering it harder to read.

Aside from being the earliest-known waqfiyya inscription, Tütüncü notes the significance of its content: In ninth-century Palestine, a waqf trust was established including two villages: Kafr Kana and Kafr Tabaria (which are apparently none other than today’s Kafr Kanna and Kfar Tavor in the Galilee, 10 kilometers from each other as the bird flies).

The endowment included 40 horses and 25 mules – healthy ones, mark you – imported from Damascus, as well as industrial facilities, for the benefit of the poor. Regarding the beasts, there is some doubt as to the nature of the endowment. The stipulation that they be healthy may indicate that the endowment of animals was annual, and if any sickened or died, they would be replaced, Abdeljaouad suggests.

As for why the origin of the steeds need be stipulated, he posits this casts on their quality: no ratty local nags for this endowment.

It bears adding that trading relations have existed since prehistory – for example, archaeologists found an obsidian blade apparently from Turkey in a 9,000-year-old village near Jerusalem, and Canaanites imported donkeys for sacrifice from Egypt 4,700 years ago. So equines originating in what is today Syria and being donated as part of an endowment in Palestine in the medieval period wouldn’t be extraordinary, per se.

For eternity

And now let us learn what this inscription says, according to Abdeljaouad.

“In the name of Allah, the Compassionate, the Merciful,” the irrevocable inscription begins. Abu Salih Hayr al-Hadim (or al-Khadim) gave as alms his farm in Kafr Tabaria and all his land in Kafr Kana, by means of an inviolable waqf, which may not be sold or given or transferred in inheritance or damaged by usury, or modified, for better or worse.

“It is permanently protected in accordance with its fundamental regulations, and [on the basis of] the shares assigned to the beneficiaries in whose favor it has been made a waqf forever and ever as long as the world and its inhabitant are faithful to their Lord, Allah, to whom belongs the heritage of the heavens and the earth,” Abdeljaouad interpreted: Allah being the “best of all heirs.”

The terms of the inscription, a legal document in every way, ends with the enjoinment regarding change and heaps curses on any of the faithful that might try, and still hope for clemency come the evil day:

“Whoever does these acts boldly, let him be cursed by Allah, by the cursers, by the Angels and by all mankind. May Allah not accept repentance or ransom from him. On the Day of Judgment, may Allah make him also among the loser,” Abdeljaouad interprets.

For all the detail prohibiting change, in fact the stele would have been a summary of a detailed legal document, likely written on parchment, in the presence of a Muslim judge and witnesses, Abdeljaouad explains. The same applies to the Ramla stele.

Which leads us to wonder: the endowment is supposed to be eternal, but today the medieval farmsteads are somewhere within two villages in Israel.

“The waqfs were supposed to be eternal, but the political circumstances and regime changes made them disappear. In this case, I think the waqf ceased after the conquest of Jerusalem by Crusaders in 1099, because the properties were appropriated by the new rulers,” Tütüncü explains.

The Crusader zeal would likely have been especially keen in the region of the Sea of Galilee and Nazareth – areas associated in scripture with Jesus’ miracles, he adds.

By the time the Crusaders were gone, nobody was around to revive the waqf and it disappeared from the consciousness of the Muslim people, he suggests. And now this stele is all that remains, bearing silent witness to this historic act of generosity and piety.