Joseph R. Friedman, MPH1,2; Helena Hansen, MD, PhD2

JAMA Psychiatry. Published online March 2, 2022. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0004

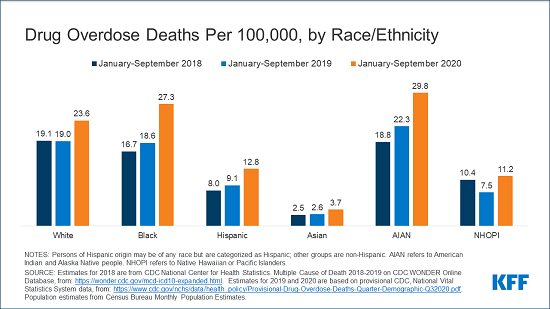

Drug overdose mortality rates have increased sharply in the US since the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020.1 Since 2015, overdose deaths have been rising most rapidly among Black and Hispanic and Latino communities.2 The pandemic has since disproportionately worsened a wide range of health, social, and economic outcomes among racial and ethnic minoritized communities. Careful attention to examining these trends by race and ethnicity is therefore warranted. Here we evaluate increases in drug overdose mortality rates by race and ethnicity before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.Methods

This cross-sectional study used anonymized publicly available data and was therefore deemed exempt from review by the University of California, Los Angeles Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was waived. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

We used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WONDER (Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research) platform and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) to calculate drug overdose death rates per 100 000 population by race and ethnicity for 1999 to 2020 (eMethods in the Supplement).3 Drug overdose deaths were defined using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision codes for underlying cause of death, including unintentional, suicide, homicide, or undetermined intent (X40-44, X60-64, X85, or Y10-14, respectively). Race and ethnicity were used as defined in the WONDER and NCHS databases. Racial and ethnic groups were defined first by ethnicity (Hispanic or Latino) and subsequently by race (non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic White). Statistical analyses were conducted using R software version 4.0.3 (R Project for Statistical Computing).Results

Overdose death rates per 100 000 among Black individuals increased from 24.7 in 2019 to 36.8 in 2020, which was 16.3% higher than that for White individuals (31.6) in 2020 (Figure). Thus, the 2020 overdose mortality rate among Black individuals was higher than that among White individuals for the first time since 1999. This is a reversal of the overdose mortality gap among Black and White individuals noted in 2010, when the rate per 100 000 among White individuals (15.8) was double (100.1% higher) that seen among Black individuals (7.9). These shifts reflect that Black communities have experienced higher annual percentage increases in overdose deaths compared with their White counterparts each year since 2012. In 2020, Black individuals had the largest percentage increase in overdose mortality (48.8%) compared with White individuals (26.3%).

The results also showed that American Indian or Alaska Native individuals experienced the highest rate of overdose mortality in 2020 (41.4 per 100 000), which was 30.8% higher than that for White individuals. Between 1999 and 2017, overdose mortality rates among American Indian or Alaska Native individuals were similar to those experienced by White individuals. Rates per 100 000 among American Indian or Alaska Native individuals first became disproportionately higher in 2019 (28.9) compared with White individuals (25.0).

Drug overdose rates among Hispanic or Latino individuals remained the lowest among the groups assessed throughout the study period (17.3 per 100 000 in 2020). However, Hispanic or Latino individuals also experienced a large percentage increase in drug overdose rates in 2020 (40.1%).

For all racial and ethnic groups assessed, the relative increases in drug overdose mortality rates observed in 2020 were higher than any prior increase between 1999 and 2019.Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we observed that Black individuals had the largest percentage increase in overdose mortality rates in 2020, overtaking the rate among White individuals for the first time since 1999, and American Indian or Alaska Native individuals experienced the highest rate of overdose mortality in 2020 of any group observed.

Recent studies suggest that an increasingly toxic illicit drug supply, characterized by polysubstance use of potent synthetic opioids and benzodiazepines as well as high-purity methamphetamine, is contributing to worsening of the US overdose crisis.1,4 The high—and unpredictably variable—potency of the illicit drug supply may be disproportionately harming racial and ethnic minoritized communities, with deep-seated inequalities in living conditions (including stable housing and employment, policing and arrests, preventive care, harm reduction, telehealth, medications for opioid use disorder, and naloxone access) likely playing a role.5,6

The increasing toxicity of the drug supply has been associated with the increased lethality of recent incarceration as a risk factor for overdose mortality,4 which may disproportionately affect American Indian or Alaska Native, Black, and Hispanic or Latino individuals as a result of structural racism in the criminal justice system. Recently incarcerated individuals have been consistently observed to have reduced opioid tolerance and less knowledge of shifts in drug potency.4

A limitation of this study is that records from 2020 were provisional and may underestimate final mortality rates. Additional methodologic considerations are discussed in the Supplement.

Drug overdose mortality is increasingly becoming a racial justice issue in the US. Our results suggest that drug overdose mortality has been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Providing individuals with a safer supply of drugs, closing gaps in health care access (eg, harm reduction services and medications for opioid use disorder), ending routine incarceration of individuals with substance use disorders, and addressing the social conditions of people who use drugs represent urgently needed, evidence-based strategies that can be used to reduce increasing inequalities in overdose rates.