| On the last day of his life, Frederick Douglass attended a meeting of the National Women’s Council. The prodigious orator and abolitionist came home to Cedar Hill, his hilltop house in the Anacostia neighborhood of Washington, D.C.; spoke with his wife at the time, Helen Pitts Douglass, about the events and future plans; clasped his hands to his chest and died that evening. It seemed impossible that such an indomitable man was gone. |

| On that final day, his meeting had been an act of reconciliation. Mr. Douglass, the only African-American to participate in the Seneca Falls convention in New York in 1848, had been staunch in his support of women’s full enfranchisement at a time when this was a divisive issue in antislavery societies in the United States and Britain. His later support of the passage of the 15th Amendment, which conferred the right to vote on Black men, came as a blow to the movement for women’s rights at a key moment. The end of the Civil War had created urgency to secure Black suffrage through the 15th Amendment, however ineffectual it became through the vise created by racist Jim Crow era policies. |

| Even with the rift over the 15th Amendment, Douglass was unwavering in his support of women’s right to vote though his sense of timing and strategy shifted. “Her right to be and to do is as full, complete and perfect as the right of any man on earth,” he said in 1888 at the International Council of Women, in Washington. “I say of her, as I say of the colored people, ‘Give her fair play, and hands off.’” |

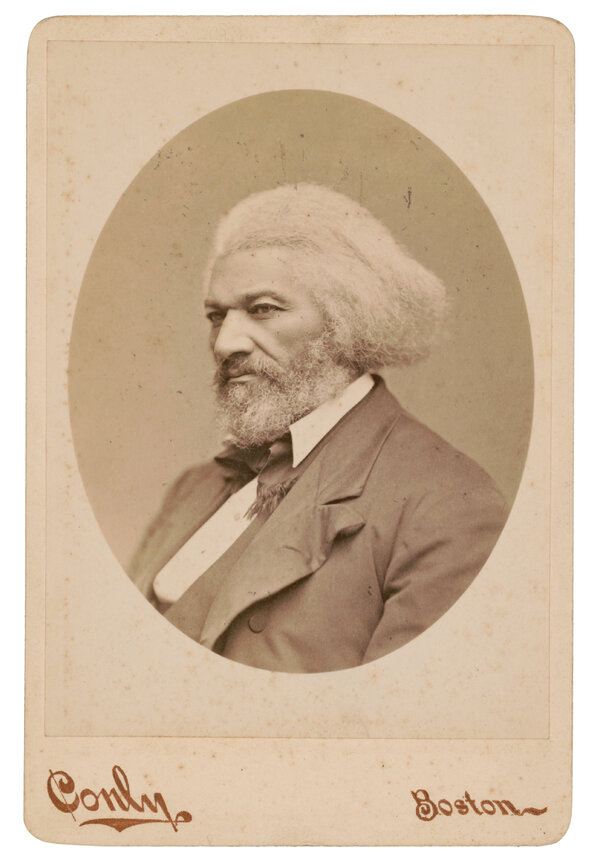

| Douglass was acutely aware that the advocacy of rights, equality and “fair play” for Black women in the suffrage movement, whose right to vote was contested even after the passage of the 19th Amendment, was inextricably connected to the power of photography. Considered the most photographed American manin the 19th century, he knew and argued that representational democracy is secured not only by laws and norms, but by the narratives fashioned by representation in culture as well. |

| At a time when the work of leading Black suffragists was often unwelcome, Black women crafted and mobilized images that became critical documents for insisting on racial equity and agency. An underexplored feature of the history of women’s suffrage is that the journey over decades coincided squarely with the use of images as a form of data to support narratives about who counts and who belongs in society. In the mid-19th century, the use, circulation and creation of images determined intimacies, aspirations and social boundaries. By the turn of the 20th century, photographs were decidedly civic currency. |

| [Read about how photographs of generations of Black suffragists offer invaluable documents about their thwarted and central roles in the history of women’s rights.] |

| The Women Who Fought Against the Vote |

| By Jennifer Schuessler |

| The sinking of the Titanic in 1912 inspired a flood of articles on seemingly every aspect of the disaster. One of the oddest appeared in The Woman’s Protest, a journal dedicated to opposing women’s suffrage. |

| In “The Lesson that Came from the Sea,” Josephine Jewell Dodge, a leading anti-suffragist, noted that when the ship started going down, the cry that went up was not “Voters first!” but “Women first!” |

| “In acquiescing to that cry the women admitted that they were not fitted for men’s tasks,” Dodge wrote. “They did not think of the boasted ‘equality’ in all things.” |

| This was not to say, she emphasized, that women were “inferior.” But the disaster, she wrote, “tends in its terribly grim way to point out the everlasting ‘difference’ of the sexes.” |

| Women at the polls (and on the ballot) are such an ordinary sight today that it can be hard to remember how long and hard women fought for the vote and the powerful forces arrayed against them, including business interests, religious organizations and the political parties, which feared an influx of unpredictable new voters. |

| But one opposition group has long inspired puzzled reactions, if not outright disbelief: women themselves. |

| As the suffrage movement picked up steam in the late 19th century, it was increasingly countered by an organized, women-led anti-suffrage movement, which mirrored its arguments, tactics and public relations strategies, including cartoons, buttons, pennants and other swag. |

| It’s tempting to dismiss the Antis, as they were sometimes called, as a bizarre footnote, or a joke. But historians argue that you can’t really understand the suffrage movement — and today’s unfinished debates about what true equality for women means — without them. |

| “You might ask, ‘How could a woman be opposed to her own rights?’” said Susan Goodier, a historian at the State University of New York, Oneonta, and the author of “No Votes for Women,” a study of the Antis. “But you have to understand what the suffrage movement was up against, which wasn’t just men.” |

| [Read about the role anti-suffragists played in the battle for the vote.] |

A portrait of Alice Dunbar-Nelson, who described in her diary “a thriving lesbian and bisexual subculture among Black suffragists and clubwomen.”Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, University of Delaware A portrait of Alice Dunbar-Nelson, who described in her diary “a thriving lesbian and bisexual subculture among Black suffragists and clubwomen.”Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, University of Delaware |

| How Queer Women Powered the Suffrage Movement |

| By Maya Salam |

| In 1920, the suffragist Molly Dewson sat down to write a letter of congratulations to Maud Wood Park, who had just been chosen as the first president of the League of Women Voters, formed in anticipation of the passage of the 19th Amendment to help millions of women carry out their newfound right as voters. |

| “Partner and I have been bursting with pride and satisfaction,” she wrote. Dewson didn’t need to specify who “partner” was. Park already knew that Dewson was in a committed relationship with Polly Porter, whom she had met a decade earlier. The couple then settled down at a farm in Massachusetts (where they named their bulls after men they disliked). |

| Dewson “made every political decision, career decision based on how it would affect her relationship with Polly Porter,” Susan Ware, a historian and the author of “Partner and I” and “Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote,” said in a phone interview. |

| Dewson was far from the only suffragist who had romantic relationships with women. Many of the women who fought for representation were rebels living nonnormative, queer lives. |

| “These kinds of non-heteronormative relationships were just part and parcel of the suffrage movement,” Ware said. “It’s not like we are having to dig and turn up like two or three women. They’re everywhere.” Including among the highest echelons of the movement. |

| [Read about how the freedom to choose whom and how women loved was tied deeply to the idea of voting rights.] |

| Suffrage at 100 |

| To mark the anniversary of the 19th Amendment, we’re revisiting the stories of how women won the right to vote in the United States. Look for a special section in the Sunday, Aug. 16 edition of The New York Times. And on Tuesday, Aug. 18, join the Times for an original play from some of the brightest young voices working today. |

| The Times commissioned “Finish the Fight,” a new production in which the acclaimed playwright Ming Peiffer (“Usual Girls”), the 2020 Obie-winning director Whitney White (“Our Dear Dead Drug Lord,” “What to Send Up When It Goes Down”) and a cast of celebrated actresses bring to theatrical life the biographies of lesser-known activists who helped to win voting rights for women. |

| “Finish the Fight” premieres at 7 p.m. Tuesday. The performance is available for free to viewers who R.S.V.P. in advance. (Real-time captioning is available for this event.) |