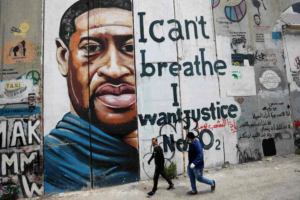

Four years after George Floyd’s murder, two Washington Post reporters reflect on the retrenchment of the racial-justice movement sparked by his death.

In their book, “His Name Is George Floyd,” Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa examined how institutional racism shaped the life and legacy of the Black man murdered on Memorial Day in 2020. Four years after Floyd’s killing, the Washington Post national reporters reflect on the retrenchment of the racial-justice movement sparked by his death.

ROBERT: One day, this March, I woke up in a hotel room in Memphis and wondered if we got it all wrong.

So many times in the two years since publishing our book, “His Name Is George Floyd,” people have asked whether there is any hope for the country.

But four years after Floyd’s murder and the so-called great racial reckoning, we were set to speak in a city whose school system had decided our book was too controversial to be taught. Other school systems had stymied discussion about systemic racism, businesses were questioning their diversity programs, and affirmative action had been deemed illegal in college admissions. Some police reforms had been undone.

The backlash feels more enduring than the reckoning itself. And on that morning, I stared at the ceiling, asking myself: What if all that protesting that consumed the George Floyd summer — not all of the racial tension that had come before — was the desperate last gasp of a movement that would inevitably fail?

Story continues below advertisement

TOLUSE: When I first heard you raise that question, I initially viewed it as an intriguing and provocative mental exercise — the kind of idea two journalists could politely debate, before moving on with their lives. But it didn’t take long before I realized that at the heart of your inquiry was something fundamental to understanding my own journey in the years since Floyd was killed.

On one hand, our book about his life had received acclaim and accolades, including the 2023 Pulitzer Prize in general nonfiction. On the other hand, we faced racist online campaigns to discredit our work, and well-meaning event attendees who asked us if the contrast between our successes as Black men and Floyd’s demise proved that racism was not the real problem.

The dichotomy reflected what was happening throughout the country, where the racial reckoning sparked by Floyd’s death seemed at risk of being washed away by waves of retrenchment and fatigue.

While we were in Memphis, we learned that the city’s efforts to enact police accountability measures would be reversed by the state legislature in the coming days.

Such erosion — also evident in schools, boardrooms, courtrooms and statehouses across the country — has further called into question the nation’s appetite for change at the pace at which it arrived in the summer and fall of 2020.

ROBERT: I figured I was spending too much time inside my head, so I decided to make some phone calls to people who I thought might help me understand just what was happening. I reached out to a former member of the school board in Shenandoah County, Va., named Cyndy Walsh. Walsh had returned to civilian life, but in 2020, she was a member of a school board that agreed to rename Stonewall Jackson High School to Mountain View High School. The removal of Confederate names and iconography was popular at the time, but four years later, the school board had six new members. And in May, the new board voted to re-rename the county’s southernmost high school after the proslavery general and American insurrectionist.

Walsh told me the reversal was both “astonishing” and “expected.” Conservatives had been organizing over the past four years to seize control of the school board. And they began making arguments that Walsh thought completely obfuscated the issue. Rather than debating the name itself, members harped on what they called a hasty decision-making period — two months — that they said could not possibly have been long enough to solicit good feedback.

There were hours of public comment on the night of the recent vote, and most residents implored the school board to keep the Mountain View name. They noted that the Stonewall Jackson name was not honoring a local hero; he was not even from their county. The name emerged in 1959 during a period of massive resistance to integration, as a way to intimidate Black students. That didn’t matter. At the meeting, one supporter of the Jackson name simply noted: “I don’t like the name Mountain View. It’s too generic, and it’s boring.”

Nonetheless, Walsh wondered if this new school board had a point. Maybe they would have received more support if they had slowed down the process. This was the hindsight on 2020. Back then, Walsh told me, the school board felt an urgency to do something. “Everything seemed to speed up at that time,” she said.

I could not help but think that this local debate — even in a county that is more than 90 percent White — was a reflection of the larger recoil from the George Floyd summer. Walsh cautioned me that things might not be so simple.

“This isn’t over,” she told me.

Story continues below advertisement

She could not stop thinking about the discomfort an all-Black school would have playing a basketball game against the Generals of Stonewall Jackson High. And she did not feel that the stubbornness of some members of her community, be they the majority or not, was reason enough to stifle necessary change. So Walsh planned to keep fighting. “It’s the right thing to do,” she told me.

There was another person that I knew who did not grow up too far from Shenandoah County: Jacob Frey, Minneapolis’s mayor during the Floyd protests. When I first met Frey in 2021, he was facing an uncertain political future. He had initially earned plaudits for his swift call to fire Derek Chauvin, the officer who had placed his knee on Floyd’s neck, and three officers who had held Floyd down. But soon, protesters would march to his home and demand he commit to abolishing the police department. When Frey told them he was not a police abolitionist, the crowd of hundreds booed and cursed him.

In retrospect, Frey told me, the past years had taught him to be a better listener — and to “take a beat.” It turned out that the vast majority of people in Minneapolis did not want to abolish the police department and supported his decisions to add behavioral health consultants to the force. He was reelected.

And then, I called someone who had been among the protesters outside Frey’s home. Donald Hooker Jr. was a chess coach who devoted himself to activism after Floyd’s death. Hooker had been to so many protests that he no longer felt affected when police sprayed tear gas. He had believed that protesters needed to try new tactics to facilitate change, so he did not mind when they burned down a police station and surrounded the car of a councilwoman until she signed a piece of paper demanding the abolition of the police department. Four years after his activism started, Hooker knew that none of those tactics produced the change he dreamed was possible.

“The police are still killing us,” he told me. Last November, Hooker stopped attending protests altogether. “I was getting so sad and burned out that I couldn’t come home and do all the normal things,” he said. “I kept thinking how we haven’t had lasting change; what we got is crumbs.”

Hooker told me he started to invest in joy. For him, that meant hosting a community chess club and sponsoring a Super Smash Bros. video game tournament during Black History Month. I asked him if all his protesting had been for naught. He gave me one of the pauses that made me feel like I’d lost my mind. “Change is going to happen,” he said. “The status quo is unsustainable. I don’t have doubts that we are going to win. I only have doubts if I’m going to be alive to see the victory.”

They were three different voices from three different perspectives, but there were so many similarities in their conclusions. All three say they are now less impulsive than in the immediate aftermath of Floyd’s death, stressing the importance of attracting more people to their cause. They wished they had taken more time to reflect during the manic rush for change. And none of them thought this chapter of American history was over.

TOLUSE: That sentiment has been echoed in some of the conversations I’ve been having as well.

Not long after our book about George Floyd was banned from that Memphis high school, we were invited to return to the city for a program that organizers described as a “truth-telling event” aimed at countering the sense of retrogression on issues of equity.

One of the people who spoke on the panel with us was Cornell Williams Brooks, a former head of the NAACP, who told attendees in spirited tones that the activism that followed Floyd’s death would not so easily be extinguished.

Months later, as I grappled with the question of which way the arc of the moral universe was bending at this moment in American history, I gave him a call to get his thoughts.

He did not mince his words as he lamented that many of the more ambitious ideas for nudging the country closer to equality — including reparations for descendants of the enslaved and strong new protections for voting rights — have largely faded from the public conversation. And he pointed out that police killings, disproportionately of Black men, have continued unabated in the years since Floyd’s murder sparked calls for overhauling policing. But that did not mean the street demonstrations of 2020 were a failure, he said.

“The lack of progress is not so much an indictment of mass mobilization and popular protests as it is a commentary on the sophistication of the forces of retrenchment in this country,” he said, noting the gap in power and resources between those aiming to preserve the status quo and those determined to change it.

“The public is keeping score,” he added, predicting that the nation is bound to face another tipping point on race in the near future. “You never know what death, what murder, what instance of injustice and inhumanity will precipitate not just mass mobilization and political protests but also electoral change.”

Story continues below advertisement

ROBERT: People often ask if we feel like we carry the legacy of George Floyd with us. I tell them it would be presumptuous of us to think so. We are but reporters with a pen and a pad and a tape recorder; Floyd was loved and beloved by his friends and family, who are the true holders of his legacy.

But I think it’s impossible to ignore what living with his story, and documenting the aftermath of his death, has done to me. I, too, hope for a future in which I do not have to live with the fear that a police officer might kill me unjustifiably, which I’ve had for most of my life. I, too, dream of an America in which folks’ biases do not impede anyone’s ability to attain their most American dreams. After all the research that we did about the lingering force of systemic racism, I yearn for its eradication even more.

Now when I read about acts of racism, I find myself uttering affirmations about moral arcs to calm down. I pride myself on being a patient and open-minded journalist, but get annoyed and aggrieved when readers approach us spewing a horrific lie that Floyd died of a drug overdose, even after the world saw footage of a police officer cutting off his oxygen supply for almost 10 minutes. And during the murder trial against Derek Chauvin, Martin Tobin, one of the world’s foremost experts on breathing, explained that Floyd’s body did not show any of the telltale signs of a death by overdose.

I think about how nine years passed between Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat and the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, and become more astonished by those activists’ persistence. Nine years. So many people who were animated to help end racial injustice after Floyd’s death told me how tired they already felt after four.

As we continued to talk to people about the book, I began having conversations with an 82-year-old man named Charles Person. Person was one of the original Freedom Riders, the group of young people who boarded buses in the early 1960s to integrate bus stops, bathrooms and lunch counters along the highway system.

Person and other Freedom Riders had been forced to escape firebombed buses and had been beaten by mobs, experiences that still bring him to inconsolable tears. Even so, he gets on Zoom meetings to speak with activists in Atlanta.

His relationship to the civil rights era was so different from what I learned in the history books. For Person, that period never ended. When I asked him what kept him going, he told me he thought of his enslaved ancestors who never got a chance to stop going. History propelled him.

My interactions with Person forced me to reexamine the fatalism I had detected among so many. I was haunted by my early interactions in the summer of 2021 with Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz (D), who was already questioning whether he could do anything more to reduce the gulf between the lives of Black people and White people in his state. Legislators did not seem interested in expansive criminal justice reform amid police shortages, and the Black families whom he had befriended were losing faith in his commitment.

“I feel like I failed” them, Walz told me at the time. “We may not get another shot at this.”

When I spoke to him last week, though, Walz told me he had learned that his persistence was important in the aftermath. He had some success establishing diversity programs, finding more money for minority businesses and enacting other reforms that he said were helping to reduce some of the country’s most glaring racial disparities. Inequality was decreasing, he believed.

“We’ve learned not to do the Minnesota thing, which is to look at disparities, say, ‘Oh that’s too bad,’ then go and eat pie,” Walz said. I told him I was surprised to hear such a sunny outlook from him, given his pessimism after the legislative session in 2021.

“Robert,” he said to me, “That was … trauma.”

TOLUSE: I’ve often wondered how George Floyd himself would have reacted to this moment. The Floyd we learned about had many reasons to be fatalistic but rejected the idea that redemption was too far out of reach.

When Floyd confided to friends that he “was in a dark place,” it was never from a sense of hopelessness. He often confronted hard times by bucking himself up and charting a path forward. “I just need a hand to get to the light,” he told one friend after admitting his despair, seeking help to get into a rehab program. “But life never ever sucks,” he wrote in a poem in the spring of 2020, stricken with covid and struggling financially but determined to embrace hope.

And even as he made and acknowledged his fair share of mistakes in life — mistakes compounded by the prevalence of systemic racism — Floyd constantly held onto the belief that the American Dream was still possible for someone like him.

That same belief drove millions of people into the streets in the summer of 2020, seeking justice and reform after his killing. Much of the activism was channeled toward that year’s presidential election. For many of the marchers we spoke to, the choice in November was clear. Then-candidate Joe Biden had visited with the Floyd family, took a knee in solidarity with the protesters and unveiled a racial-justice agenda that championed many of their priorities. President Donald Trump, by contrast, had called the activists “thugs” and pledged to unleash the full force of the U.S. military to quash their movement. When Trump was defeated, many of the same protesters took to the streets again, this time in celebration.

Story continues below advertisement

But four years later, the sense of clarity and relief has been replaced by a growing sense of disillusionment, both with the rematch between the two candidates and the broader political system. Only 62 percent of Black Americans now say they’re “absolutely certain to vote,” down from 74 percent in June 2020, according to a Washington Post-Ipsos poll conducted last month. The 12-percentage-point drop outpaced the four-point drop among Americans overall, from 72 percent to 68 percent. Concerns about the economy, inflation, the war in Gaza and the halting pace of racial progress have driven some to consider backing Trump, voting for a third-party candidate or staying home.

Biden told us in 2021 that the battle between America’s ideals and its troubled racial history “is never a rout, it’s always a fight.” As the country gears up for a presidential rematch in November, the outcome could hinge on whether that message resonates with Americans who are questioning whether the fight is worth it.

When I asked Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) how he is grappling with that question after his attempts to pass bipartisan legislation on policing failed, he said disengaging could not be an option.

“This process is slow and painful, and as activists, we encounter setbacks that are meant to discourage our search for progress,” he said. “But we cannot give up. I have not given up.”

ROBERT: One week after we left Memphis, George Floyd’s brother, Philonise, joined the mothers of Eric Garner and Trayvon Martin, as well as the parents of Tyre Nichols, on a panel. Philonise praised state and municipal governments that had passed measures to ban chokeholds like the one that killed his brother, and bemoaned how disengaged federal lawmakers had become on this topic.

Still, Philonise encouraged the audience to continue pushing; there is little more than they can do but that. Over and over again, Tolu, I often found inspiration that so many have not given up on the American promise.

Over the course of our reporting, I came to believe this: Pessimism is the ultimate American privilege. It is the feeling held most easily by those whose lives would still be functional, and maybe even satisfactory, if nothing changed.

And it is the feeling so often rejected by those who have the least, who, like George Floyd, wake up each day in hopes that a better tomorrow might be possible. This form of American hope was a defense mechanism, but it was also an engine that kept them engaged in the world.

I often return to George Floyd’s final actions as an act of remarkable faith. On May 25, 2020, he woke up on a day he did not know he would die. As he took his last gasps under the knee of a police officer, realizing his time on Earth was coming to end, he told his story through a weakened, strained voice. He decried the actions of the officer as coldblooded, cried out to his mother, and then he repeated over and over again, to his children and to his friends, that he loved them.

Before we started reporting, it was easy for us to presume that Floyd’s words were incidental. They were not. The three words people associated him most would not be “I can’t breathe.” He would constantly say to people, “I love you.” And, for a flickering summer, those expressions of love seemed to change the world. The expression of his heart meant something, and it fueled a movement that he would never get to witness.

When I was a college student, I took inspiration from Joan Didion. The title of one of her anthologies became one of my favorite aphorisms: “We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live.” These four years have taught me that we simply don’t tell stories in order to live; we tell stories because we get to live. And in living, there is always chance that the moral arc — if there is one — can bend toward a better world. And in that possibility, there is still an opportunity the country will, one day, live up to its own ideals.

Robert Samuels, national enterprise reporter, and Toluse Olorunnipa, White House bureau chief, interviewed hundreds of people for their book, “His Name Is George Floyd: One Man’s Life and the Struggle for Racial Justice,” which was released in paperback this month.

Source: https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2024/05/25/george-floyd-anniversary-retrenchment/