By Sindya N. Bhanoo Feb. 15, 2020 at 12:00 p.m. EST

In 2003, the Havasupai Indians of Arizona issued a banishment order against Arizona State University, forbidding researchers from setting foot on their reservation in response to prior unauthorized DNA research done on tribal members’ blood samples. In 2002, the Navajo Nation banned DNA studies out of fear of how their samples might be used by scientists.

But many genome scientists believe that health care can be improved with the use of genetic information and are concerned that if indigenous communities do not participate, they will be left behind. This has led to a major effort, particularly among younger researchers of indigenous descent, to work collaboratively with communities, consulting with their leaders and holding preliminary meetings where members help design research projects.

Genetic testing may soon be part of preventive health care

“It means having conversations with people over beer, dinner and music to gather ideas about what people are interested in,” said Keolu Fox, a genome scientist at the University of California at San Diego, who is Native Hawaiian and whose research focuses on people of Polynesian descent. “It means speaking in a church, setting up a meeting, just talking to people. Asking questions.”

The efforts are critical, Fox said, so that the health disparity between the Western world and the indigenous one does not increase. Today, American Indians and Alaska Natives have a life expectancy that is more than five years shorter than that of other Americans, and they are more likely to suffer from conditions such as diabetes and liver disease.

Although there have been significant advances in genome sequencing technology in recent years, which could help personalize and improve medical care, a paper published in Nature Genetics earlier this year found that far more research is done on people of European ancestry than on non-Europeans.

As of 2016, 80 percent of participants in genetics studies are of European descent, although the group makes up only about 16 percent of the world’s population. The future consequences of this gap could be serious.AD

“Sequencing the genomes of individuals is going to change clinical care,” said Fox. “Based on a genomic profile, we could give a higher-resolution, personalized treatment.”

Fox’s latest research project is on the island of Moorea, in French Polynesia, and stems from long conversations with locals. Fox discovered that islanders wanted to know whether high rates of thyroid cancer and leukemia were connected to nuclear testing that was done there by the French government years ago. Some research has been done on this, but Fox said he hopes to dig deeper.

“What if we can differentiate between cancer that is caused by exposure to nuclear radiation and cancer that is inherited normally? That’s powerful,” he said. “What if I could show that the effects of nuclear radiation are transgenerational? You see how different it is to frame it that way? That has impact on my community, on my people.”AD

Alyssa Bader recently completed her doctoral research at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She worked with the Metlakatla First Nation in British Columbia for her dissertation research. Her ancestors belonged to the tribe.

Before starting her research, which focused on looking at changes in diet over time using ancient DNA and DNA samples from living Metlakatla Indians, she met with community members and talked about her research and interests, and asked about their interests.

“It wasn’t just a matter of getting permission,” she said. “The goal of the project was to integrate a lot of different types of data for it to be about the experience of ancestors.”

Her research included DNA, as well as isotype analysis, but it also included many interviews with tribal elders about their observations on community dietary changes over time.AD

The results of her research have not been published, but she says that community members played an important role in helping her interpret the data when she went back in June.

“I said, ‘Here are the results, and this is what they mean to me as a scientist; now let’s talk about it using the deep knowledge you have,’ ” she said. “This went beyond consulting. We were co-producing new knowledge.”

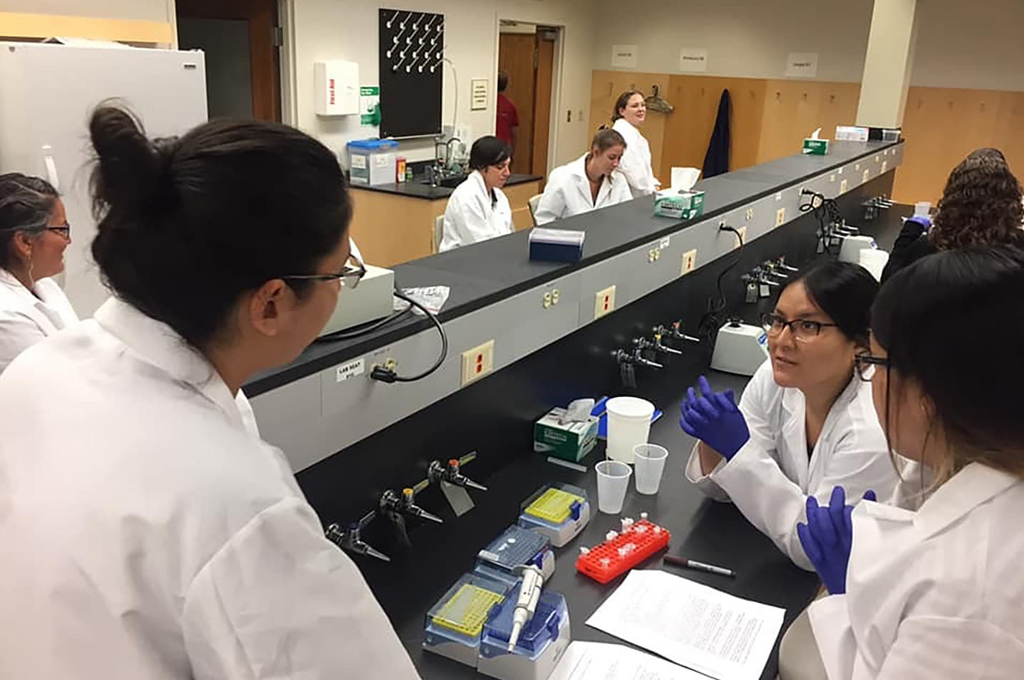

Both Bader and Fox participated in a program called the Summer internship for INdigenous peoples in Genomics, or SING, when they were students and say it shaped their research philosophy. The program, which runs as an annual summer workshop for researchers and members of indigenous communities, was started by Ripan Malhi, a genome scientist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Bader’s dissertation adviser.AD

Malhi said he first observed the misuse of data from indigenous communities, and the distrust on the part of community members, when he was a graduate student in the mid-1990s at the University of Washington. Since then, he has worked hard to change the way students think about research. The training program, which gets most of its funding from the National Human Genome Research Institute, began in 2011 in the United States and has since expanded to Canada, New Zealand and Australia.

“Having better science isn’t just about keeping science in the ivy tower of academia; science is about helping communities,” Malhi said. “In the past, researchers were collecting blood samples and thinking of people as resources, as a way to get what they needed to advance their careers.”

Over 100 researchers have participated in the training program, and most are indigenous, Malhi said. He has been pleased to see a rise in the number of indigenous students in the field, but it is still low. American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders make up just four-tenths of 1 percent of U.S. residents in science and engineering fields.AD

Krystal Tsosie, a doctoral student in genomics at Vanderbilt University, who is Navajo and assists with the training program Malhi helped found, is aiding in building the first indigenous people-led biobank in the United States with members of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. The facility, which will collect, catalogue and store samples of biological material for research purposes, will be housed on tribal land.

“We need to do the research,” she said. “We need to be our own scientists.”

This type of work, which relies on indigenous communities to not only be involved in research but conduct it, could rebuild trust and change attitudes, and in the long term, improve medical care, Tsosie said. The Navajo Nation is reconsidering the ban it set in place forbidding DNA studies. “They may not fully lift it, but maybe partially,” Tsosie said.AD

Malhi recalled a song by Floyd Red Crow Westerman, an American Indian artist, that criticizes anthropologists who studied Native American populations.

The song, called “Here Come the Anthros,” goes:

“And not a cent of funded money

“That the anthros get to spend

“Is ever given to their

“Disappearing feathered friends.”

“The song is actually pretty amusing, but it speaks to how this was not a one-time incident. It was happening again and again,” Malhi said. “Before this generation of researchers, most researchers in the genomics space had questions they wanted to answer about peopling of the Americas and the world, things that were of concern to them in academia. Now it’s about community impact.”