The invasion begins innocently enough: A goldfish paddles the secluded waters of an at-home aquarium, minding its own business, disturbing no native habitats.

The real trouble comes later, when the human who put it there decides it’s time for a change. Not wanting to hurt the fish, but not wanting to keep it either, the pet’s owner decides to release it into a local lake, pond or waterway. That decision, experts say, is well-meaning but misguided — and potentially harmful.

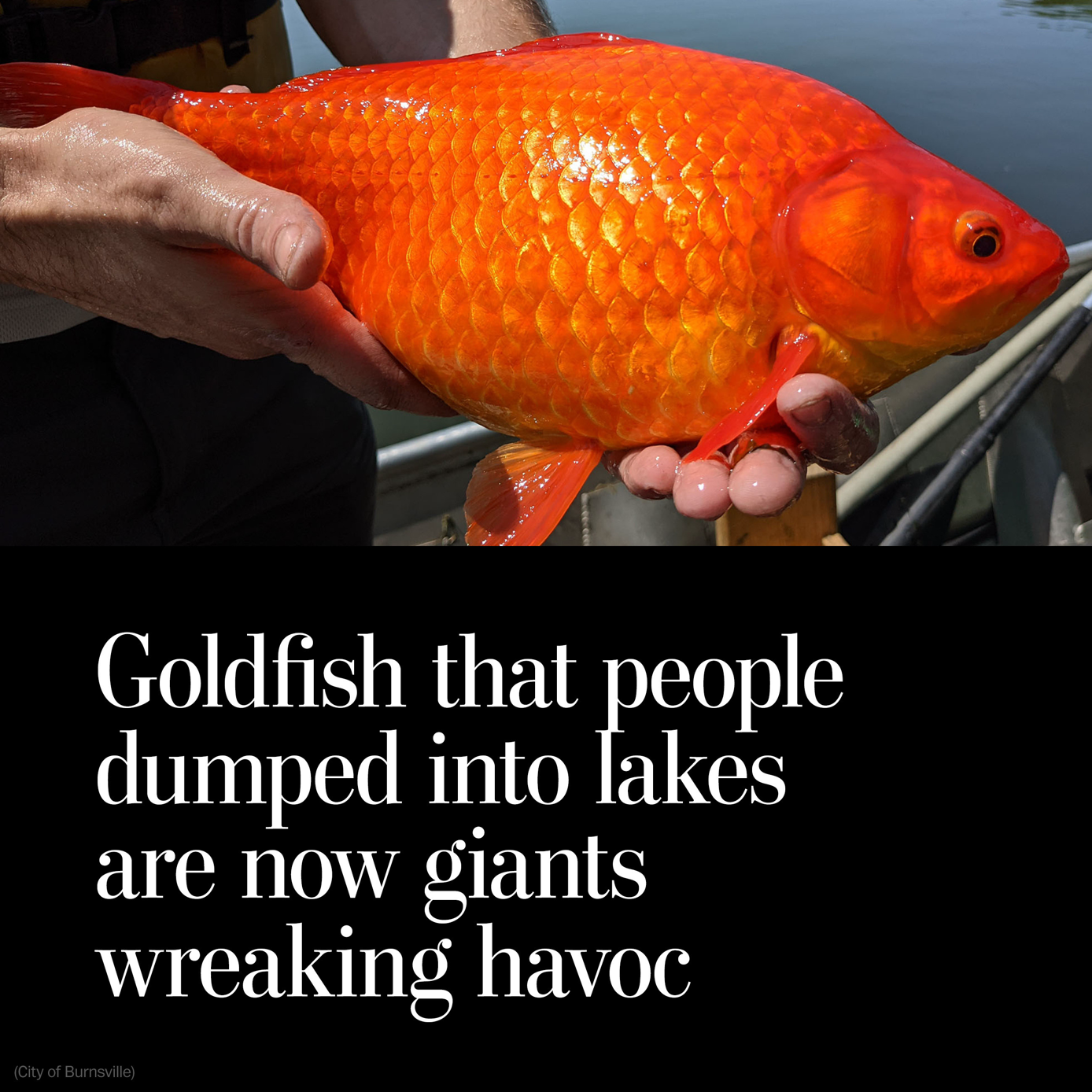

Officials in Burnsville, a city about 15 miles south of Minneapolis, demonstrated why late last week, when they shared photographs of several massive goldfish that were recovered from a local lake. The discarded pets can swell and wreak havoc, the city warned.

“Please don’t release your pet goldfish into ponds and lakes!” the city wrote in a Twitter post, which had been liked and retweeted more than 15,000 times Sunday night. “They grow bigger than you think and contribute to poor water quality by mucking up the bottom sediments and uprooting plants.”

Burnsville, along with neighboring Apple Valley, began surveying the lake’s goldfish population after residents complained of a possible infestation. Working with the company Carp Solutions, which specializes in controlling water pests, the cities sent a team to investigate, and even it was surprised by the size of the fish it found.

“You see goldfish in the store and they’re these small little fish,” Caleb Ashling, Burnsville’s natural resources specialist, said in an interview. “When you pull a goldfish about the size of a football out of the lake, it makes you wonder how this can even be the same type of animal.”

Far from being an innocuous domestic animal, a goldfish freed in fresh water is an invasive species, an organism that is introduced to an environment, can quickly reproduce, outcompete native species and destroy a habitat. And even though they get less attention than invasive organisms such as Asian carp or zebra mussels, goldfish appear to be a growing problem in bodies of water across the United States and around the world, triggering warnings from government officials in Virginia, Washington state, Australia, Canada and elsewhere.

“A few goldfish might seem to some like a harmless addition to the local water body — but they’re not,” the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources advised this year.

The problem has been getting worse in recent years, said Przemek Bajer, who owns Carp Solutions and is an aquatic invasive species professor at the University of Minnesota. The most probable sources are former pets and their progeny, he said.

“They seem to be getting more and more widespread,” Bajer said. “You think about how many of those fish are sold nationally and how many are being released. That’s a pretty big vector of introduction.”

The most popular and interesting stories of the day to keep you in the know. In your inbox, every day.

Also known by the scientific name Carassius auratus , goldfish can live to be 25 years old, weigh as much as four pounds and measure well over a foot long. They’re also surprisingly resilient: They can survive in severe conditions and can weather winters in bodies of water that have frozen over, living for months without oxygen. This quality, Bajer said, “makes them really, really tough and allows them to dominate certain types of ecosystems.”

Goldfish, like their common carp relatives, feed at the bottom of lakes, where they uproot plants and stir up sediment, which then damages the water’s quality and can lead to algal blooms, harming other species.

“Goldfish have the ability to drastically change water quality, which can have a cascade of impacts on plants and other animals,” Ashling said. “They are a major concern.”

Once goldfish are in one body of water, they can move on to others, and they can be tricky to evict. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources said the fish are able to “work their way through city storm water ponds and into lakes and streams downstream with big impacts, by rapidly reproducing, surviving harsh winters and feeding in and stirring up the bottom.” It is illegal to release goldfish in the state’s public waters.

In Carver County, which is not far from Burnsville, goldfish have plagued a chain of lakes for at least two years, frustrating water management officials and costing the locality money as it tries to battle the problem.

Last year, county workers removed an estimated 30,000 to 50,000 of the fish in one day. The origin of the problem, the county said, probably is “one or more individuals illegally dumping pet goldfish over the years.”

This year, Carver County signed an $88,000 contract with a consulting firm to study how to manage and remove the shoals of goldfish.

Paul Moline, Carver County’s planning and water management manager, told county commissioners that the fish “are an understudied species” with “a high potential to negatively impact the water quality of lakes.”

In 2018, Washington state officials said they would spend $150,000 rehabilitating a lake near Spokane that had become so overrun by goldfish that it was hurting the trout population. An invasive-species expert in Alberta called the Canadian province’s problem “scary.” And about two months ago in Virginia, state wildlife officials certified a record after an angler reeled in a 16-inch goldfish, but they warned that “pet owners should never release their aquatic organisms into the wild.”

Ashling and his colleagues in Burnsville are trying to determine the scope of their problem, but they’re hoping their early findings will discourage other pet owners from ditching their fish in public waters — which, in the Land of 10,000 Lakes, are sacred.

“People are trying to be nice, but they don’t realize that goldfish can really have a lot of unintended consequences,” Ashling said. “Most people really care about their lakes and ponds, but you may be causing problems you weren’t aware of if you let them go there.”