During history major Maddie Henderson’s internship at the National Museum of the American Indian, she sought to learn more about the Indian boarding school era and how forced assimilation has affected the dissemination of cultural practices generations later, including within her own family.

Family, kinship, and togetherness are the cornerstones of Indigenous life and identity; those themes connect hundreds of tribes and offer a sense of communal strength and power. Growing up hundreds of miles away from the Turtle Mountain Chippewa reservation in Belcourt, North Dakota, I have relied on my family’s retelling of the past and often feel disconnected from the Indigenous part of myself. Fortunately, the consequences of physical distance from my extended family and community have been dismantled by the closeness I feel when I notice that I’ve inherited so much from them. As if part of our birth right, my grandpa has made sure that his mischievous smile and sense of humor infiltrated every one of his children and grandchildren. Similarly, I know that my passion for education and knowledge comes from my dad, and my eagerness to question and explore comes from my aunt. And the more I learn about my family and our history, the more I am struck by another common theme that connects Indigenous communities: resilience.

During my internship at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), I researched Indian Boarding and Residential schools because I sought to learn more about the boarding school era and how it affected the dissemination of cultural practices generations later. My ancestors and elders attended boarding schools, though I’m unsure of the exact number. It is a painful subject to discuss and the school records are incomplete. Through my research, I hoped to learn about what my relatives may have experienced during their time in the schools.

Unfortunately, the boarding school era is often omitted and forgotten in the teaching of U.S. and Canadian history; however, during my time with the Smithsonian, I had the opportunity to fill gaps in my knowledge and better understand the complexities, atrocities, and nuances surrounding the boarding school period. I also uncovered that healing from this traumatic era comes in many different forms; some generations seek to learn and understand, some express their emotion through art and music, and others keep the experience locked away like a distant memory.

I learned that the United States government felt it had an “Indian problem,” whereby the presence of Native people living on reservations impeded its goals of territorial expansion and dominance. The government then pushed for ways to forcibly assimilate Native people and move them away from their communities, especially children. According to an investigative report conducted by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in May 2022, boarding schools for Native children were part of the government’s Indian territorial dispossession “solution” to the “Indian Problem.” With expansionist goals in mind, the United States and Canadian governments sought to assimilate American Indian children into standardized, “American” culture by sending them to boarding and residential schools away from their homes, families, lifeways, and land.The Civilization Fund Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in 1819, sparked the assimilation era in the United States. Education became one way to enforce “civilization” efforts and led to the establishment and creation of approximately 408 federally supported on-reservation and off-reservation Indian Boarding Schools in 37 states. The schools began operating in 1819 and continued until as recently as 1969. The Carlisle Indian School, established in 1879 in Pennsylvania, was the blueprint for other federal schools and followed a military-school model. Carlisle founder Richard Henry Pratt designed his curriculum to “Kill the Indian…and save the man” by forcing the students to unlearn their cultural heritage through punishment and then encouraging only mainstream culture. Similarly, in Canada, 139 residential schools operated between 1831 and 1996. In 1831, the Mohawk Institute in Brantford, Ontario, accepted its first boarding students; and in 1931, 80 residential schools were operating in Canada, the most at any one time.

While these schools operated under the guise of improving education and access through forced assimilation of Indian children in the United States and Canada, the consequences of the boarding school era are impossible to overlook and harmed many tribal nations to their core. Children as young as four years old were forcibly removed from their families (as boarding school attendance was federally mandated). Children spoke about the physical, mental, and emotional abuse that occurred at these schools. By 1926, nearly 83% of Indian school-age children attended boarding schools.

Boarding school attendance was mandated by the government (whether granted by parental consent or not) and when the children arrived, they were forced to cut their hair, give up their traditional clothing for military-style clothing, and go by new Anglo-American names instead of their family-given ones.

One of the most significant consequences of the boarding school era was the loss of culture and language. At these schools, Indian children were forbidden to speak their tribal languages and often were harshly punished if they did. This practice was tactical—the school administrators understood the power of language in culture. Oral histories, lifeways, and philosophies are communicated through and survive by common language. Without shared language, these traditions and stories could not endure.

Similarly, the students’ Indigenous spiritual practices were forcibly replaced with Christianity. Teachers often ridiculed Indigenous cultural ways, and children felt humiliation and shame around them. This approach then could terminate the continuation and wellbeing of American Indian and First Nation spiritual practices.

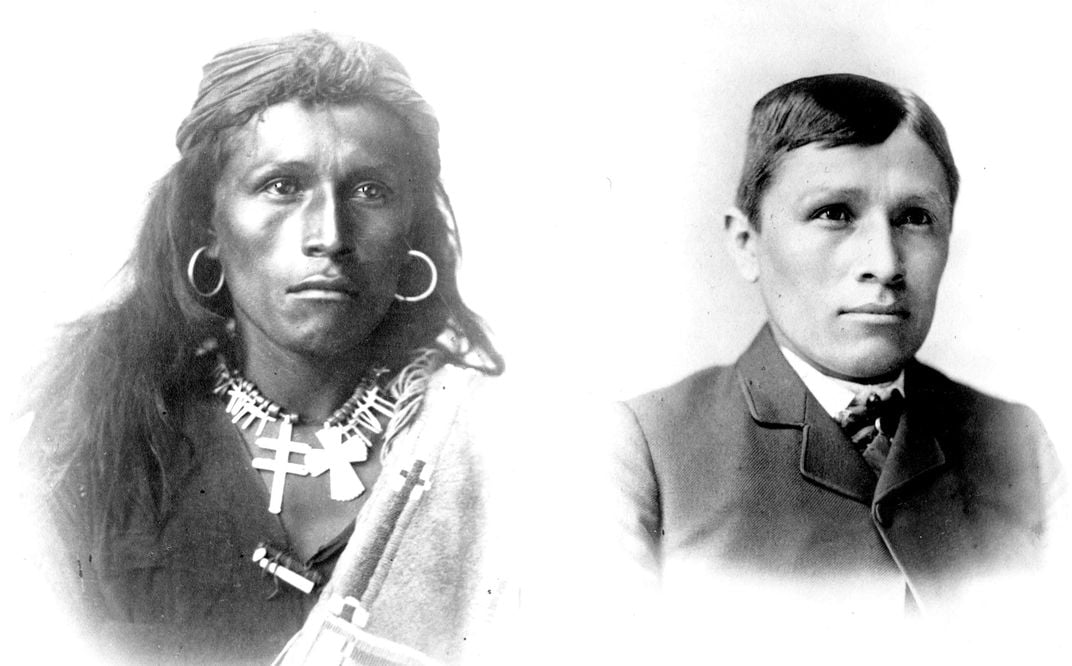

The schools’ curricula primarily focused on creating Native students who were “marketable” to mainstream American society. Female students were taught the skills and tasks of an American homemaker (cleaning, cooking, sewing, and laundry), while male students practiced carpentry, farming, and blacksmithing. During standard academic classes like reading or history, teachers ensured that lessons explicitly stressed American beliefs and values. Often, schools emphasized athletics as an extension of American ideals like practicing teamwork and promoting physical strength. Some students even played sports professionally, like football player Jim Thorpe (Sac and Fox), or competed in the Olympics, like runner Tsökahovi Tewanima (Hopi). The athletic accomplishments of the schools’ current and former students were often used as a marketing tactic by administrators and a demonstration of how the boarding schools were teaching young people how to be good, true Americans. The same administrators also sent benefactors postcards with two photos of one student, one photo depicting the child having just arrived at the school and one showing a “successful” transition to American culture. These transformation photos were used as forms of justification for the boarding school mission.

I, myself, am mournful of a vibrant, deep cultural heritage I may have inherited and had the opportunity to connect with without the forced assimilation and subsequent loss of traditional knowledge. The loss of identity, language, ceremonies, traditions, self-esteem, and sense of place has presented itself in the modern-day as unresolved grief, mental health issues, substance abuse, economic hardship, and relationship issues.

Tragically, sexual and physical abuse were frequently reported by students attending boarding schools, and some students died from disease, abuse, or malnourishment. Some students ran away or disappeared, never returning to their families. While the number of students who died at residential schools in the United States is still disputed, a report by the U.S. Interior Department in 2022 declared that at least 500 Native American, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian children died while attending Indian boarding schools run or supported by the U.S. government. It noted that, “The Department expects that continued investigation will reveal the approximate number of Indian children who died at Federal Indian boarding schools to be in the thousands or tens of thousands” and that more than 50 gravesites were identified with more likely to be found. According to a separate report by the University of Manitoba’s National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, at least 6,000 children died at residential schools. In 2021, two horrific discoveries of unmarked graves at former schools were a sobering call to action. Canadian officials found 751 unmarked graves at the cemetery of the former Marieval Indian Residential school in Saskatchewan, and, just months later, researchers found unmarked burials of 215 students at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia using ground-penetrating radar (GPR). These two discoveries unearthed more irreversible trauma for family members of boarding school survivors.

For most children, leaving boarding school and returning to their homelands proved to be another challenge to overcome. After years of mental, emotional, and physical separation from their homes, the children’s relationships with their families and cultures were irrevocably changed. First, many students who grew up speaking their Native language at home lost any sense of fluency after spending the majority of their lives being shamed and banned from speaking them. Many elders did not speak English, only their tribal language, so children often lost the ability to hear stories, learn about cultural practices, or simply communicate with their grandparents. The loss of language alone has weakened the cultural fabric of American and Canadian Indigenous communities forever. Many children were taught to feel ashamed of their culture and traditional lifeways during their boarding school years and reentered their past lives as completely different versions of themselves. They felt lost and out of place when returning home, torn between their given identity and their learned one.

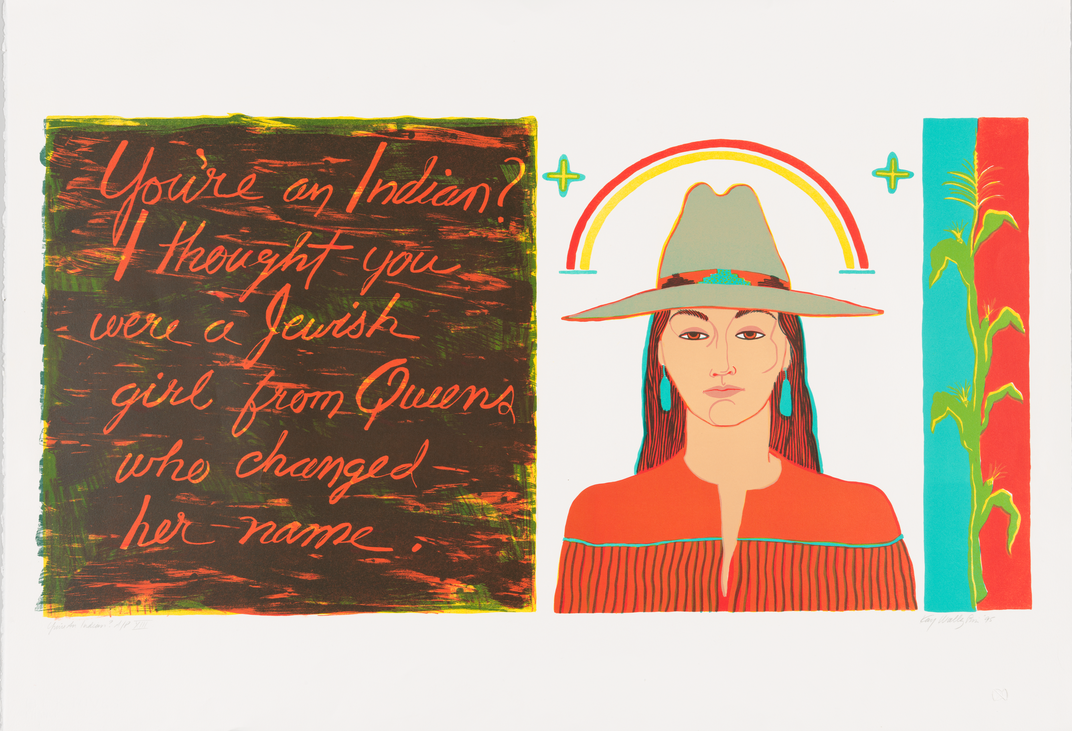

The mass cultural loss left generations of Indigenous people questioning themselves, their identity, their spirituality, and their worth. Artist Kay WalkingStick (Cherokee), daughter of a boarding school survivor, understands her relationship with her identity through her artwork. The WalkingStick family has a well-established tribal history; her ancestors opposed the signing of the Treaty of Echota in 1835 and accompanied Principal Chief John Ross to demonstrate in DC, and her grandfather became one of the first Native lawyers to practice law on both tribal and non-tribal courts in Oklahoma and Arizona. Though WalkingStick and her siblings were raised in Syracuse, New York by their non-Native mother, Emma, “being Indian was simply part of who the family was.” Despite the physical disconnection between her absent father and the home he grew up in, WalkingStick wrestled with her identity as a multicultural, Cherokee woman and the historical greatness of her family on the canvas. Her series “Talking Leaves” includes several self-portraits layered with ignorant quotes. One quote reads, “You’re not an Indian. You weren’t born on a reservation!” The statement illustrates both WalkingStick’s personal experiences with people questioning her identity as well as the public’s misinformed perception about what Indians look like. WalkingStick, and many Indigenous people like her, break the mold of what public perception, thinks, hopes, or wants her to be and depicts this phenomenon in her artwork.

The misconceptions surrounding Indigenous identity are harmful and scary, especially as someone who is already questioning where they belong. When others tell you who or what you are, that can become the truth. While children in the boarding school system had their culture berated, their intelligence mocked, and their futures prescribed, modern Indigenous peoples face a similar challenge in understanding their identities. With little media representation and rampant, false stereotypes, Natives today often view the path forward as unclear and murky. It is easy to feel disconnected from a culture that is portrayed as only existing in the past and not the present.

I, myself, am mournful of a vibrant, deep cultural heritage I may have inherited and had the opportunity to connect with without the forced assimilation and subsequent loss of traditional knowledge. The loss of identity, language, ceremonies, traditions, self-esteem, and sense of place has presented itself in the modern-day as unresolved grief, mental health issues, substance abuse, economic hardship, and relationship issues.

Healing begins with recognizing the lasting consequences of the boarding school era. While the path is not linear, healing can include expressing pain through art. For example, the NMAI in DC is currently hosting the exhibition, Red is Beautiful, a retrospective of artist Robert Houle (Saulteaux Anishinaabe), who is a residential school survivor. Houle addresses his trauma from his boarding school experience through depicting shadowy demon figures from his dreams and then painting the shamans who helped heal him. In the museum’s gallery space, the set of demons and shaman paintings face each other. The art evokes a sense of unbelievable emotion, reckoning, and healing.