A shocking new exhibition reveals the thriving postwar careers of artists the Führer endorsed as ‘divinely gifted’. Many made public works that remain on show today

A photograph from 1940 shows three conquering Nazis in Paris against the backdrop of the Eiffel Tower. Within a few years one of these men, Adolf Hitler, was dead by his own hand; another, Albert Speer, was writing his memoirs in Spandau prison, having eluded a death sentence at the Nuremberg trials. But the third, Arno Breker, was alive and free, making sculptures in the new West Germany that in their bombast and iconography echoed those he had made during the Third Reich.

Breker typified the thesis of a remarkable new exhibition in Berlin, that Hitler’s favourite artists and sculptors survived the Third Reich and filled public spaces of the new Federal Republic of Germany with artworks scarcely different from those they had produced between 1933 and 1945.

In 1957, for instance, Breker was commissioned to make a sculpture installed outside the Wilhelm-Dörpfeld-Gymnasium, a school in Wuppertal. The result was a larger than life bronze of Pallas Athene, the Greek goddess of war and wisdom, helmeted and poised to throw a spear. “The iconography is just the same as that of the Nazi era,” says the exhibition’s curator, Wolfgang Brauneis.

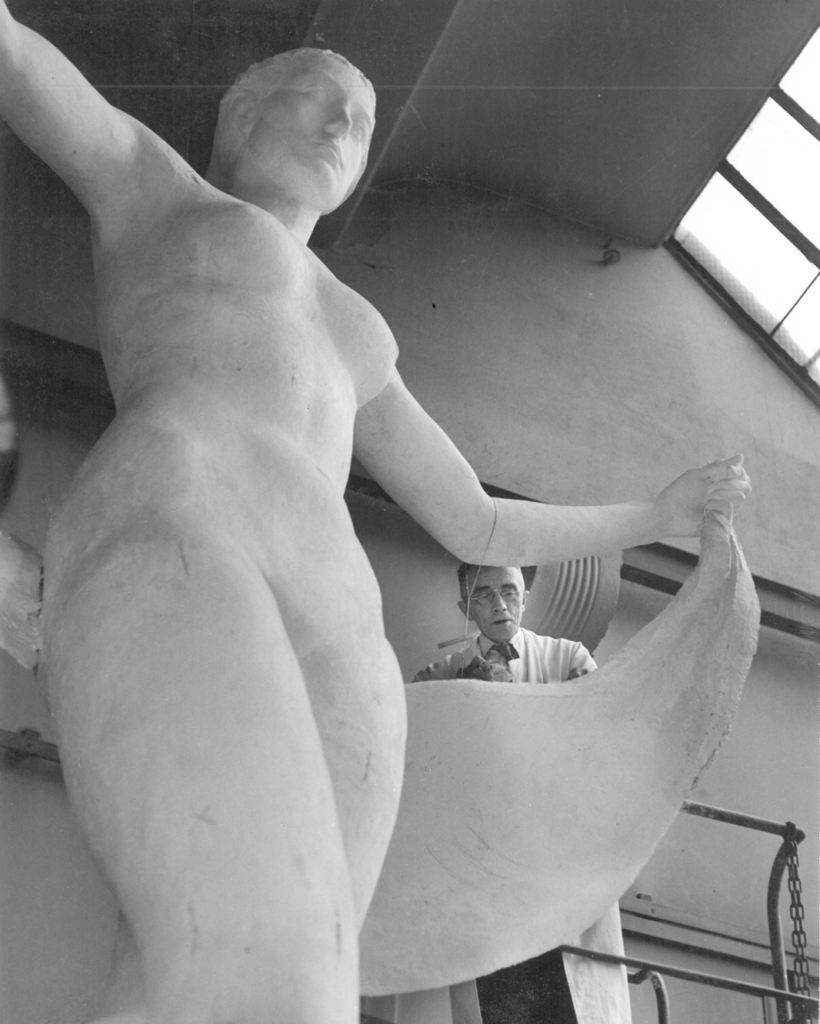

Breker had been lionised by the leaders of the Third Reich In 1944, he figured on a list of 378 “Gottbegnadeten” or “divinely gifted” artists whom Hitler and Nazi chief propagandist Joseph Goebbels exempted from military duty. In 1936, Hitler made Breker official state sculptor, giving him a large studio and 43 assistants. He was commissioned to make two athletic sculptures for the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. Three other sculptures – The Party, The Army and Striding Horses – were prominently displayed at the entrance to Speer’s New Reich Chancellery in Berlin.

From 1937 until 1944, Breker was among hundreds of German artists whose work was shown in the Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung in Munich, an exhibition designed to showcase what National Socialists thought of as the right kind of art. Much of it eulogised German sacrifice in the first world war or neo-classical heroic sculptures such as Breker’s Prometheus.

Goebbels juxtaposed this purportedly great art against its opposite. He ordered another exhibition of so-called “Entartete Kunst” (degenerate art) at Munich’s Institute of Archaeology. It brought together 650 paintings, sculptures and prints by 112 primarily German and often Jewish artists, including Georg Grosz, Emile Nolde, Otto Dix, Franz Marc and Paul Klee.

After the war, Breker’s status as image maker for the Nazis, one might have thought, would have made him persona non grata in the new German republic. On the contrary, he benefited from an old boys’ network of Nazis: his Pallas Athene in Wuppertal was made possible by the intercession of fellow “divinely gifted” architect Friedrich Hetzelt.

Despite being fired as professor of visual arts in Berlin after being named as a Nazi fellow traveller in 1948, Breker went on to thrive professionally, designing sculptures for Dusseldorf’s city hall. He also made busts of political leaders including Konrad Adenauer, the Federal Republic’s first chancellor. True, when the Pompidou Centre in Paris in 1981 staged a Breker retrospective there were protests from anti-Nazi activists. Four years later though, his posthumous reputation was boosted when the Schloss Nörvenich was given over to an Arno Breker Museum that can still be visited today.

Breker was not an unusual case. The Deutsches Historiches Museum exhibition includes more than 300 works of art – tapestries, murals, sculptures – made by Nazi artists or fellow travellers after 1945. Among them is work by Hermann Kaspar whom Speer commissioned to design mosaics, frescoes, floors, friezes and wood inlays for the New Reich Chancellery. Hitler was most taken with the inlay of the oversized desk in the Führer’s study that, Speer recalled in his memoirs, depicted the mask of Mars, god of war, behind which a sword was crossed with a lance. “Well, well,” Hitler reportedly told Speer. “When the diplomats sitting in front of me at this table see it, they will learn to be afraid.”

After the war, Kaspar received numerous state commissions, including the national coat of arms tapestry in the Senate Hall of the Bavarian state parliament. Most strikingly, though, Kaspar finished work he had started under the Third Reich. He began his monumental wall mosaic for the Congress Hall of Munich’s German Museum in 1935, finally completing it in 1955.

Kaspar’s postwar success bears out a remark made by the great German Jewish philosopher Max Horkheimer when he returned from American exile to the University of Frankfurt in the late 1940s. “I attended a faculty meeting yesterday and found it too friendly by half and enough to make you throw up,” he wrote. “All these people sit there as they did before the Third Reich. Just as if nothing had happened … they are acting out a Ghost Sonata that leaves Strindberg standing.”

Brauneis agrees with this assessment: “In West Germany and Austria, if not East Germany, many of the most successful artists were Nazis.” The ghost sonata carried on as if the Holocaust had not happened. Brauneis’s exhibition is aimed at bringing a neglected chapter in German history to light.

The official version, after all, is that West Germany was no haven for Nazis and that after 1945 a radical new aesthetic emerged. Indeed, a parallel exhibition at the museum tells the history of Documenta, the contemporary art show that takes place in Kassel every five years. When federal president Theodor Heuss opened the first Documenta in 1955, artists who had flourished in the Nazi era were not allowed to exhibit there since they were deemed unsuited to the modernist, anti-Nazi self-image of the young republic.

Brauneis argues that the hidden history he unveils undermines that flattering image. “The truth is that these ‘divinely gifted’ artists had close ties with the cultural-political programme of the Federal Republic.”

Consider Willy Meller. He had created sculptures for Berlin’s Olympic stadium, and others for the Nazis’ Prora holiday resort. After the war, Meller thrived professionally, making sculptures for the German postal service, a federal eagle for the Palais Schaumburg in Bonn, then the official residence of the Federal Chancellor. Meller even sculpted a work called The Mourning Woman for the Oberhausen Memorial Hall for the victims of National Socialism, which opened in 1962. “When The Mourning Woman was unveiled,” says Brauneis, “nobody seemed to notice that a ‘divinely gifted’ artist had been commissioned to make a sculpture for a centre devoted to recording Nazi crimes.”

Indeed, Brauneis points out that when there were objections in the press or among art critics to publicly commissioned art in West Germany, their complaints rarely had anything to do with the artists’ Nazi credentials. Rather, what united critics, press and public alike was hostility to modern art in the public sphere.

It is as if the dismal dialectic set up by Goebbels in Munich in 1937 – on the one hand heroic, neoclassical German art sanctioned by the Nazis, and on the other modern art made by Jews and “degenerate” foreigners that often ended up being burned by Nazi functionaries – was still playing out in the first decades of West Germany’s existence.

Dissenting voices finally emerged. But what’s especially striking is how much of the postwar work of these Nazi artists survives, barely noticed, in public spaces in Germany. Raphael Gross, the Deutsches Historisches Museum’s president, recalls that when he lived in Frankfurt he would pass by a sculpture every day on his way to work at the city’s Rothschild Park. “Until recently, I didn’t know it had been commissioned during the Third Reich and installed after the war.”

The park, named after the Rothschild family who had bought the property in 1837, was appropriated by the Nazis and its palace destroyed in a 1944 RAF bombing raid. Today, the park includes a statue called Der Ring der Statuen depicting seven nude allegorical figures by Georg Kolbe, commissioned in 1941 but only erected in 1954.

How odd that a park that only after the war reverted to the Jewish name the Nazis had erased could today display a sculpture by one of Hitler’s favourite artists. In 1939, Kolbe created a portrait bust of the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, which was given to Hitler as a birthday present. Kolbe, to be fair, was one of the few Third Reich artists to have work shown in both Munich’s Degenerate Art show and the Nazi-sanctioned Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung across town.

What should be the fate of these sculptures, tapestries and murals made by Nazis and fellow travellers? Should they be destroyed, retired from public view or just contextualised with helpful labels? The first option, I suggest to Gross and Brauneis, should not be ruled out. After all, there is a rich history of destruction of public art. In 2003, a weightlifter took a sledgehammer to the giant statue of Saddam Hussein in Baghdad. During the so-called Leninfall in 2014, some of the 5,500 statues of Lenin were pulled down in Ukraine. When last year the statue of slave trader Edward Colston was thrown into Bristol’s dock, historian David Olusoga wrote in the Guardian: “[T]his was not an attack on history. This is history. It is one of those rare historic moments whose arrival means things can never go back to how they were.”

Gross and Brauneis think the issue is less clear cut in the German case. “We must go case by case,” says Gross. “There can’t be a general rule.” Brauneis argues that in some cases explanatory notes are enough. “Sometimes rather than destroying the past we have to learn about it and then live with it even if that is uncomfortable.”

“Divinely Gifted”. National Socialism’s Favoured Artists in the Federal Republic is at the Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin until 5 December

… we have a small favour to ask. Since we started publishing 200 years ago, tens of millions have placed their trust in the Guardian’s high-impact journalism, turning to us in moments of crisis, uncertainty, solidarity and hope. More than 1.5 million readers in 180 countries have recently taken the step to support us financially – keeping us open to all and fiercely independent.

With no shareholders or billionaire owner, we can set our own agenda and provide trustworthy journalism that’s free from commercial and political influence, offering a counterweight to the spread of misinformation. When it’s never mattered more, we can investigate and challenge without fear or favour.

Unlike many others, Guardian journalism is available for everyone to read, regardless of what they can afford to pay. We do this because we believe in information equality. This way, everyone can keep track of global events, understand their impact on people and communities, and become inspired to take meaningful action.

We aim to offer readers a comprehensive, international perspective on critical events shaping our world – from the Black Lives Matter movement, to the new American administration, Brexit, and the world’s slow emergence from a global pandemic. We are committed to upholding our reputation for urgent, powerful reporting on the climate emergency, and made the decision to reject advertising from fossil fuel companies, divest from the oil and gas industries, and set a course to achieve net zero emissions by 2030.