It’s been 18 months since Joshua Wong finished serving his last conviction, but it will be at least 2022 before he’s a free man again.

The prominent activist was handed his latest sentence of 13.5 months in a small courtroom in Hong Kong’s working-class Sham Shui Po district Wednesday as efforts to quell dissent in the semiautonomous Chinese enclave escalate. This is the toughest sentence that 24-year-old Wong, who has been in and out of detention since he was a teen, has received.

He and two other members of the disbanded political party Demosistōhad pleaded guilty to various charges, including incitement, in relation to a rally outside police headquarters in June 2019.

Co-defendants Ivan Lam and Agnes Chow were handed sentences of seven and 10 months respectively. For Chow, the youngest of the trio at 23 years old, this will be her first time in prison. After hanging her head low throughout most of the hearing, she finally burst into tears upon hearing the sentence. For Wong it will be his fourth stint behind bars in three years.

Though the defense lawyers had argued for leniency for their young charges, Magistrate Wong Sze-lai shot them down. In her hour-long verdict, she emphasized the necessity of deterrence after large-scaleand often violent demonstrations paralyzed the financial hub over the second half of last year. She called imprisonment “the only appropriate” option.ADVERTISING

Analysts see the ruling as casting a pall over the broader pro-democracy movement. “These three are widely seen as icons pushing the limits of democracy in Hong Kong in defiance of Beijing,” says Willy Lam, a political scientist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “Their sentencing will strike fear into the hearts of pro-democracy supporters.”

Authorities have arrested more than 10,000 protesters since June last year in a crackdown that has netted everyone from pensioners to primary school students. But it’s done little to resolve the underlying tensions in a city where much of the population lionizes democratic ideals but is ultimately controlled by the Chinese Communist Party.

Outside the courthouse, pro-Beijing and pro-democracy supporters loudly heckled each other in front of camera crews, highlighting the deep polarization that continues to permeate the territory even as street protests have evaporated. After the verdict, two Beijing supporters sprayed each other with champagne to celebrate the imprisonment of “the rioters.” University students who came to support Wong, Lam and Chow openly cried.

Wong, the international face of Hong Kong’s protest movement, has long helped galvanize the city’s youth to take to the streets. As such, he’s no stranger to handcuffs, wigged barristers or gavels coming down against him. Lately, he’s also gotten a taste of solitary confinement in the prison hospital after an X-ray reportedly revealed a foreign object in his stomach. None of it has dampened his resolve to keep being a thorn in Beijing’s side.

He and his co-defendants were not allowed to give statements to the press before or after their sentencing. But as Wong was whisked away, he shouted, “We will hang in there.”

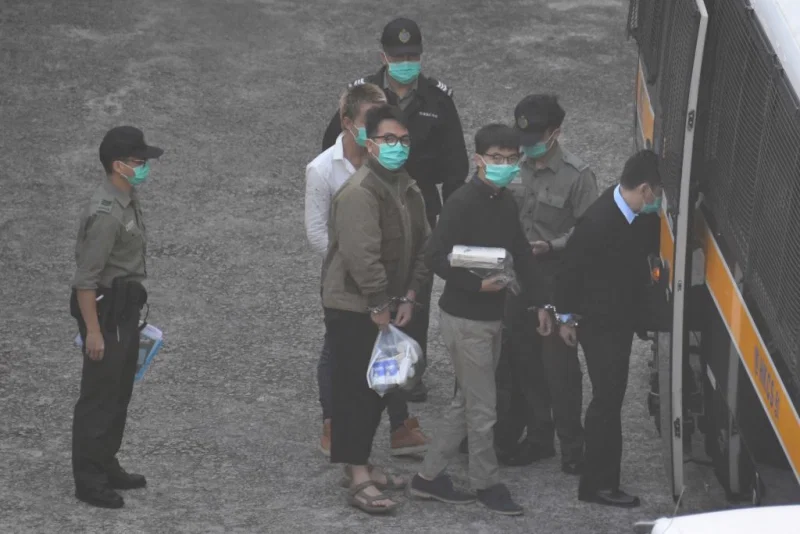

Agnes Chow (L), Ivan Lam (C), and Joshua Wong (R) arrive at the West Kowloon Law Courts building on Nov. 23, 2020 in Hong Kong. Miguel Candela Poblacion—Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Agnes Chow (L), Ivan Lam (C), and Joshua Wong (R) arrive at the West Kowloon Law Courts building on Nov. 23, 2020 in Hong Kong. Miguel Candela Poblacion—Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Hong Kong’s struggle for democracy

Like many young Hong Kong activists, Wong displays something of a martyr mentality — believing self-sacrifice to be the cost of fighting for democracy.

Speaking to TIME this past May, he described living with a constant fear that at any moment he could experience arrest, kidnapping or even extraordinary rendition. “No matter what, I am always targeted by Beijing,” he says.

For years, strange vans and shadowy men have trailed him. He and his girlfriend were once assaulted when leaving a movie theater. He has been pelted with eggs and fists and branded a “traitor” by the Chinese foreign ministry. Last year, he was snatched off the street and stuffed into a minivan by police.

“No one wants to be constantly at the point of being stigmatized, being attacked, being prosecuted or being jailed,” says Nathan Law, Wong’s colleague and a fellow democracy campaigner who has spent time in prison himself. “But the political situation in Hong Kong has evolved to the point where, as an activist, political persecution is inevitable,” he says.

Law is now in self-exile in the U.K. and is being sought by Hong Kong police under a new national security law for allegedly colluding with foreign forces, a charge for which he could face up to life in prison.

Hong Kong’s youth are not the only ones facing repercussions over last year’s uprising. Veteran activists like 82-year-old Martin Lee and 72-year-old Margaret Ng are among those arrested. But it is high school and university-aged students who predominantly thronged to the front lines.

“Their passion for political reform has been contagious…burning Hong Kong like some wildfire,” says Claudia Mo, a former pro-democracy lawmaker. But, she adds, they “overestimated” the leniency they would be shown.

“It was more than a gamble,” she says. “They thought by displaying their passion and determination they could bring about changes for the better.”

Hong Kong’s decades-long struggle for greater autonomy, however, is freighted with all kinds of caveats and nuances, not least because some in the territory relish closer ties with the world’s number two economy and see subversives like Wong not as freedom fighters but as wanton troublemakers shattering the city of 7.5 million’s reputation for efficient commerce.

“They have done what hurts Hong Kong, so I hope they get what they deserve,” Johnny Tam says outside the courthouse, wearing a t-shirt with the logo “Johnny Patriotic 101” and wielding a Chinese state media-branded megaphone.

The scrappy fight over the former British colony’s future has only been further complicated by U.S. involvement. To some, this contest embodies a broader clash of civilizations: East v. West, Washington v. Beijing, liberalism v. authoritarianism. Given this context, the Chinese government has framed its intervention as a necessary assertion of sovereignty over a rebellious enclave, while the West decries the affront to Hong Kong’s autonomy.

The international response has been swift and mostly ineffective. The Trump Administration, which has sanctioned 14 Hong Kong and Chinese government officials, has mustered the most bellicose rhetoric, but the U.K. is tip-toeing around the idea of taking Beijing to international court over breaching the terms of the handover deal that saw the former British colony retrocede to China in 1997. Canada, Germany and Australia are also taking in a new class of refugees as political dissidents flee what was once the world’s safest city.

Joshua Wong’s rise to prominence as an activist

Born in 1996, nine months before the colony’s handover back to China, Wong grew up as part of a cohort that jokingly refers to itself as the “chosen” generation. They came of age with the clock ticking after Hong Kong was given a 50-year adjustment period to life within China. As the trajectory progresses, fears have steadily mounted over perceived attempts by the Communist Party to erode the very liberties that distinguish Hong Kong — its free press, independent courts and protest culture — from the rest of the country. Whatever political reality materializes in 2047, when the delineation between liberal enclave and the mainland disappears, they will inherit it.

Wong, who was raised in a deeply Christian household, traveled regularly to the mainland on missions to spread the Gospel. But his proselytizing soon morphed into political soliloquies. Scholarism convenor Joshua Wong speaks to the media on Oct. 1, 2013. Nora Tam—South China Morning Post/Getty Images

Scholarism convenor Joshua Wong speaks to the media on Oct. 1, 2013. Nora Tam—South China Morning Post/Getty Images

At just 14 years old, Wong took on the city’s Beijing-backed proxies and scored a rare victory. He banded students together in a group called Scholarism to block a “national education” curriculum designed to bolster fealty by teaching, among other things, that Chinese Communist Party rule is superior to democracy. After an estimated 100,000 people rallied on the streets in 2012, the government backed down.

But it was 2014 that propelled Wong to international fame as the precocious poster child for the Umbrella Movement, which sought direct elections for the city’s leader, among other political concessions. Wong was handcuffed for the first time, and detained for 46 hours, after storming a public square near the government’s headquarters.

“I have known Joshua since he was quite young and he is relentless,” says Mo, the legislator. “They are trying to put an end to his relentlessness.”

The Umbrella Movement ultimately failed, but so did the attempt to quash the aspirations of young activists. Their generation was instead politically invigorated.

“We’re all just ordinary young people coming out to campaign to make a positive change, to hold the government accountable, to get our right to vote and to elect our leaders,” says Law, the exiled campaigner.

But in doing so they have lived anything but ordinary lives.

Wong has described his schoolboy self as a dokuo, the Japanese term for young men more interested in their video games than pursuing girls. But he also appeared on the cover of TIME as “The Face of Protests” and was the subject of a Netflix documentary, “Teenager vs Superpower.”

Celebrity status followed, though he has emphasized the leaderless nature of Hong Kong’s democracy movement and was not a figurehead in the most recent protests.

Local reporters have covered his every move with tabloid-like obsession, charting his (mediocre) college-entrance examination results, following him on dates and inundating his email inbox, leaving him with a constantly pinging phone and little time to indulge his gaming hobby. From his gawky, prepubescent days he has lived and breathed activism, knowing it would earn him Beijing’s wrath.

And yet he recently described prison as a relief from the pressure of continuous interviews.

Wong is facing additional protest-related charges over a demonstration in October last year and a commemorative memorial of the June 4 Tiananmen Square massacre. Chow was arrested earlier this year for suspicion of inciting secession under the national security law, but she has not been charged.

After he was remanded last week, Wong posted a statement via friends calling for attention to be paid not to his own plight but to a dozen Hongkongers who were arrested at sea in August as they were attempting to flee to Taiwan. They are now being held in the mainland on a spate of charges. “We’re not fearless, but you are the braver ones,” he said.

“I’m still learning to conquer the fear and I believe you are with me along this journey.”