One sunny afternoon in July 1976, 26 children and their bus driver vanished on the ride home from school in Chowchilla, California, a close-knit farming town of 5,000 nestled in the San Joaquin Valley.

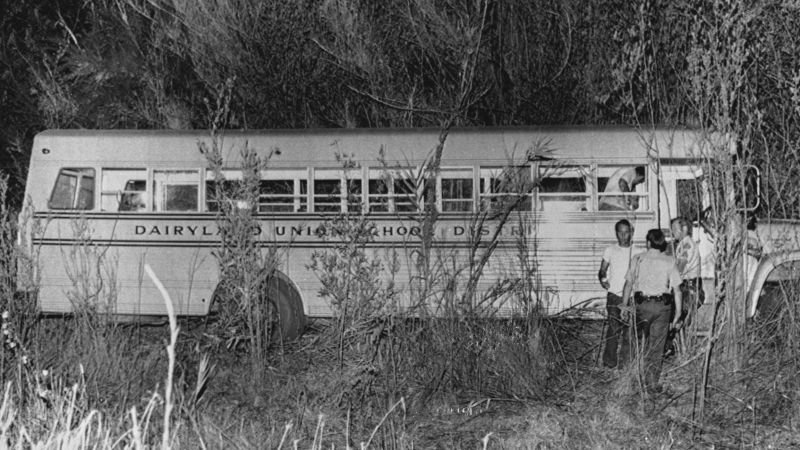

When police found the school bus abandoned in a ditch a few hours later, they realized that something was amiss.

At 3:54 p.m., three armed men — their faces masked with pantyhose — had cornered the bus on a lonely road and taken the children and their bus driver, Ed Ray, hostage. Held at gunpoint, they were split up, loaded into two vans and driven 11 hours to an abandoned rock quarry over a hundred miles away.

There, the kidnappers forced Ray and the children into a trailer buried deep underground. Leaving the hostages in the dark with a few mattresses, they piled dirt on top and sealed the kids inside a makeshift subterranean prison.

The kidnappers planned to ransom the Chowchilla kids, all between the ages of 5 and 14 years old, for $5 million.

But after 16 hours, Ray and two of the older boys pried the roof open and helped the other 24 crawl out. Police brought them to a prison, where medical experts gave the all-clear: The kids were a little shaken up, doctors thought, but aside from a few bruises and some minor urinary tract problems because they’d been holding in urine, they’d managed to survive without injury.

By then, the Chowchilla kidnapping was an international news sensation, with many headlines claiming that the children had “bounced back.”

Few thought to look at what the kidnapping had done to the children’s mental health. There was little consideration for how its effects might follow them into adulthood. After all, the field of child trauma psychiatry was still in its infancy.

Most experts believed that kids were endlessly resilient, that they’d just “get over” traumatic events. Diagnoses for post-traumatic stress disorder, even for war veterans, didn’t yet exist.

“There was the wish that children would recover, forget about the event and go on with their lives as though it never happened,” said Dr. Spencer Eth, chief of mental health with the Miami VA Healthcare System, who was not involved with the Chowchilla case.

But one doctor decided to take a closer look.

‘100% were having problems’

In the aftermath of the Chowchilla kidnapping, a Los Angeles organization took the kids to Disneyland in an effort to help them recover. The local school offered little in the way of therapy or counseling.

One mental health professional predicted that that only one of the 26 would be emotionally affected by the kidnappings.

But after Dr. Lenore Terr arrived in Chowchilla in November, she found that prediction was dead wrong. Parents were terrified because, five months after the incident, they could still hear their kids screaming in their sleep.

“No parent wanted to admit his kid was the one in 26,” Terr said in CNN Films’ documentary “Chowchilla,” which debuts at 9 p.m. ET/PT on Sunday. “By the time I got out there, 100% were having problems.”

Then a child psychiatrist training in San Francisco, Terr had long been fascinated by the burgeoning field of child trauma research: what happened, she said, to kids who were “scared to death but hadn’t died.”

When a colleague sent Terr an article about the Chowchilla kidnapping, she realized that it was a natural case study that she’d been waiting nearly a decade to find: a group of kids who all experienced the same traumatic event.

Although they were physically unharmed, all of them – from the youngest to the oldest – were changed forever.

“That kidnapping and that threat of death left an imprint that many of them never fully recovered from,” Eth said. “And we know that now, decades later, that is the usual course of events following catastrophic trauma.”

Terrors and nightmares

Over the next year, Terr would meet with a small group of parents and 23 child survivors who had remained in Chowchilla, interviewing each one for at least an hour. Often, she said, they’d run for two or three.

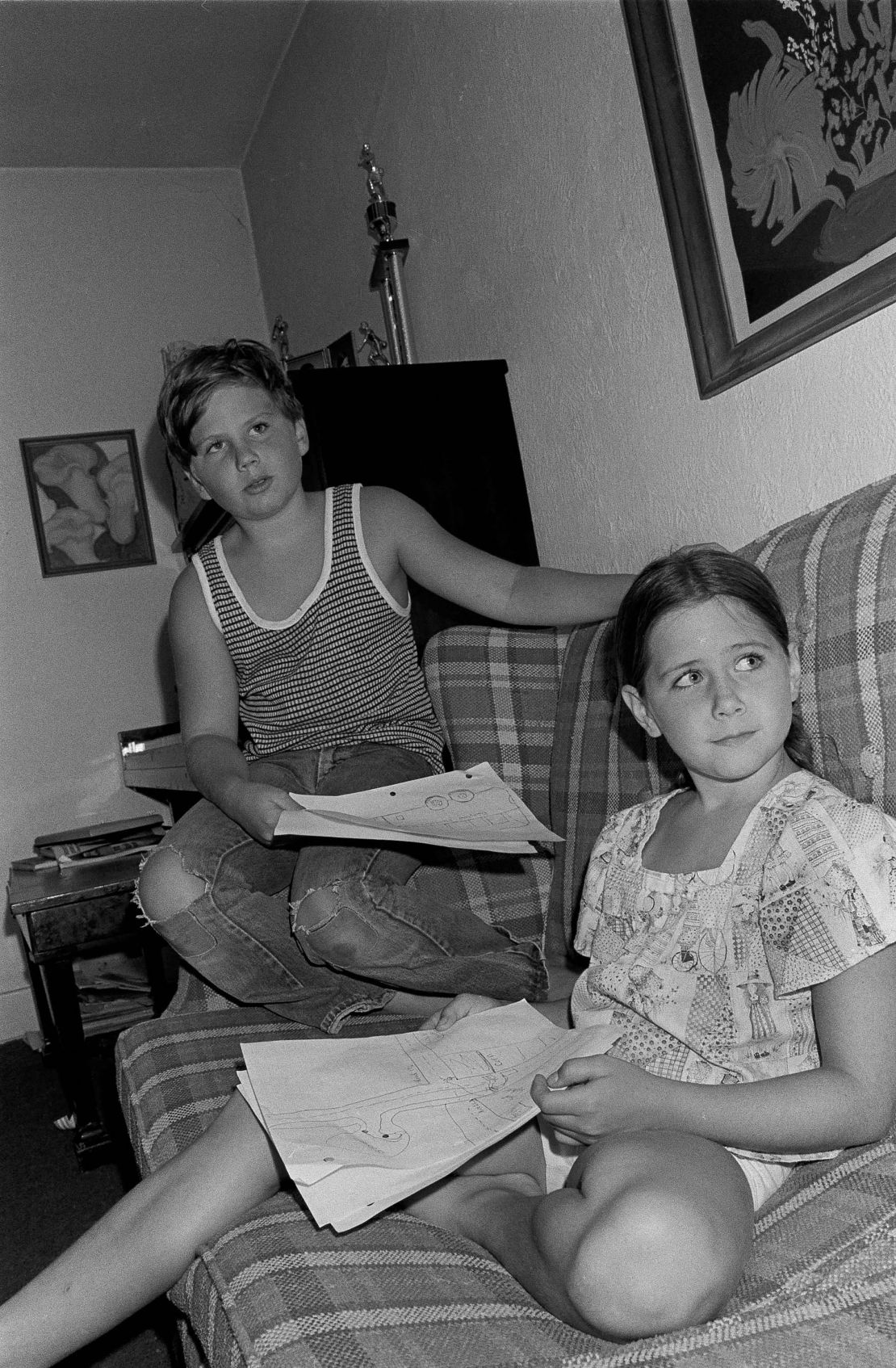

Every child she talked with carried mental scars from the kidnappings. They manifested differently: For some, their self-esteem plummeted, while others became paranoid and anxious at seeing strange vans.

In fact, 18 months after the kidnapping, one of the older boys shot a BB gun at the driver of an unknown car parked near his house, an unwitting Japanese tourist whose car had broken down.

Night terrors were common among the children, as well. At the time, the Chowchilla parents were told not to enter their kids’ rooms. Doing so, experts thought, would “reward” the behavior of having nightmares.

“When we got home, I thought everything would be OK,” Jennifer Brown Hyde, who was 9 years old during the kidnapping, said in an interview for the film. “I can remember having nightmares immediately. My mom tells me I started sleepwalking, and I would just come into their room in shock, and I would tell them ‘they’re killing me.’ ”

In several cases, Terr found, children had dreamed of their own deaths: of being lined up and shot or being killed by the kidnappers on the bus. For Terr, they were an indication that the kids’ “trauma-shattered” minds had come to expect death.

All the children Terr interviewed also struggled with fears related to kidnapping. Twenty of the 23 feared being kidnapped again. The vast majority feared everyday experiences: being alone, the dark, strangers and loud sounds. Eight had such acute anxiety that they screamed, ran or called for help when faced with one of these everyday things.

“Those demons were gonna keep us forever,” Larry Park, who was 9 years old during the kidnapping, told the filmmakers.

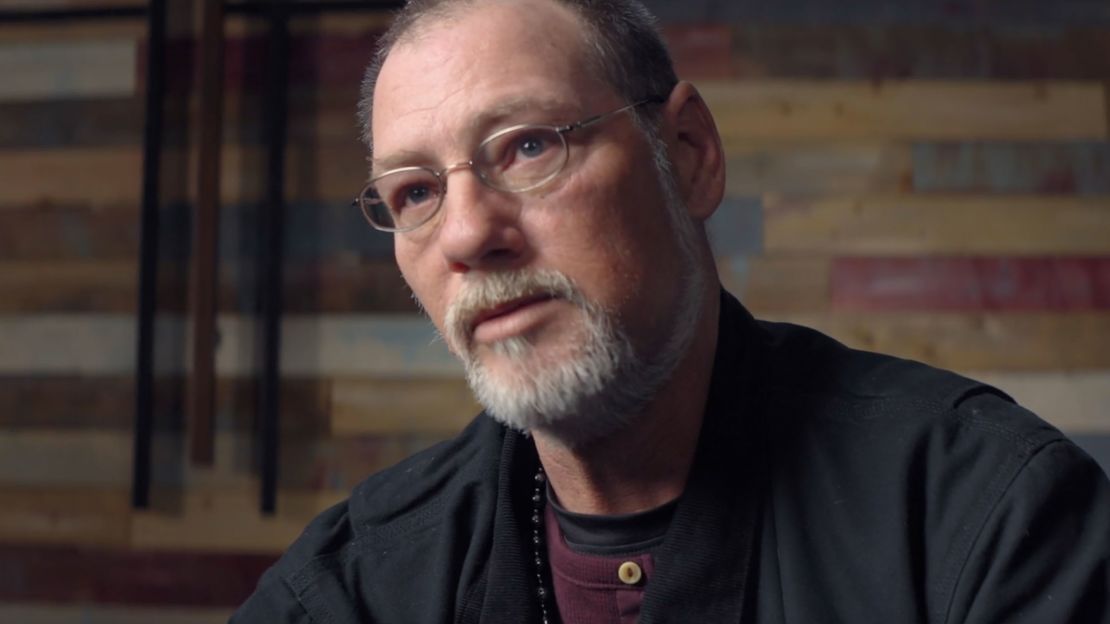

For some, the psychological toll of the kidnappings became consuming. Mike Marshall was 14 years old when he helped lead the kids’ escape from the underground trailer. When staying in Chowchilla became too much to bear, his family left to try to forget the past.

Around the first anniversary of the kidnapping, Terr reported, Marshall took the cushions off the couch and punched them for two hours every day for two weeks.

“I put myself back in there,” Marshall said in an interview for the documentary “Thinking how I was going to die.”

‘Some of it gets worse’

Years later, the Chowchilla kidnapping still lingered in the minds of survivors.

At a four-year follow-up, Terr observed that every child still exhibited post-traumatic effects, such as a deep sense of embarrassment or continued nightmares. Each one suffered from a fear of common, mundane objects, though several had begun to overcome them.

“When we get to be adults, childhood trauma doesn’t go away,” Terr told the filmmakers. “In fact, some of it gets worse.”

Terr went on to follow the Chowchilla children for five years, publishing landmark research that was among the first to focus on the experience of children who experience trauma.

Her research with the Chowchilla victims became seminal in the field of childhood psychiatry, showing that children were not immune to trauma, as previously thought. Much like with adults, Terr described how the consequences of kids’ trauma could linger, with implications reaching far into adulthood.

At 19, Marshall was getting blackout drunk every night, and he was using drugs as a coping mechanism to forget about the kidnapping. To date, he says, he’s been to rehab at least seven times.

“I just didn’t want to remember any more about the kidnapping,” he said in the film. “I just wanted it to go away.”

For Park, the kidnappings consumed his thoughts long after he’d become an adult. The gunmen were arrested after several days and sentenced to prison, but for years, he would constantly replay the kidnapping in his mind, fantasizing about ways to punish them.

“There was anger building in me that infested every aspect of my life,” Park said in an interview for the documentary.

And to this day, it’s still challenging for Hyde to enter the underground storm shelter near her home in the Midwest. The ladder leading underground reminds her too much of the trailer in which she was held captive nearly half a century ago.

‘Heroes’ in the field

Today, mental health experts recognize that Terr’s work in Chowchilla paved the way for the modern understanding that childhood trauma can have lasting consequences.

“We’ve learned a lot since Chowchilla, and Dr. Terr was an absolute pioneer,” said Dr. Elissa Benedek, a child psychiatrist and the former president of the American Psychiatric Association. “I think everyone recognizes that children are traumatized by these events and that trauma can persist.”

Over time, Benedek added, mental health experts learned that trauma can be cumulative, with multiple traumatic events adding up to place children at a higher risk of long-term consequences.

And unlike in 1976, post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, exists as a clinical diagnosis for children who’ve experienced catastrophic events. Health-care providers now use evidence-based treatments that can help children struggling with trauma, Eth said.

“From a scientific standpoint, it was a landmark event,” Eth said. “The Chowchilla work of Lenore Terr and then subsequent work by others has established child PTSD as legitimate and as a condition that calls for evaluation and treatment.”

That improved understanding of trauma, Terr says, has also changed how we respond to crisis situations. After the school shootings in Columbine and Sandy Hook, for instance, mental health counselors were on the front lines to help survivors.

“They paved the way for us to understand more contemporary things,” Terr said of the Chowchilla survivors in the film. “What happens when you force away children from parents at a border? What happens to children at some of these horrible school shootings?

“The Chowchilla children are heroes,” she added. “And they continue to teach us what childhood trauma is … 50 years after the fact.”