She became the national youth poet laureate at age 16; six years later, she read her poem at Joe Biden’s and Kamala Harris’ historic swearing-in.

Like most of us, Amanda Gorman has been cooped up at home because of the pandemic. In her case, that’s meant staying in her West Los Angeles apartment binge-watching “The Great British Baking Show.” Unlike most of us, she got some very exciting news recently via Zoom: She’d been handpicked to read a poem at President Joe Biden’s inauguration.

The first lady, Jill Biden, is a fan of her work and convinced the inaugural committee that Gorman would be a perfect fit.

Gorman, all of 22, became the youth poet laureate of Los Angeles at age 16 in 2014 and the first national youth poet laureate three years later. On Wednesday, she became the youngest poet to write and recite a piece at a presidential inauguration, following in the considerably more experienced footsteps of Maya Angelou and Robert Frost.

Her precocious path was paved with both opportunities and challenges, an early passion for language and the diverse influences of her native city. Gorman grew up near Westchester but spent the bulk of her time around the New Roads School, a socioeconomically diverse private school in Santa Monica. Her mother, Joan Wicks, teaches middle school in Watts. Shuttling among the neighborhoods gave Gorman a window onto the deep inequities that divide ZIP Codes.

“Having a mom who is a teacher had a huge impact on me,” said Gorman, who witnessed her ability to empower young people through language. Long before she began reading her own poetry aloud in grand spaces for grand occasions — from the Fourth of July to the inauguration of a new president of Harvard University — Gorman was falling in love, simultaneously, with the written and spoken word.

Her relationship with poetry dates at least to the third grade, when her teacher read Ray Bradbury’s “Dandelion Wine”to the class. She can’t recall what metaphor caught her attention, but she remembers that it reverberated inside her.

Gorman still keeps a children’s version of “Jane Eyre” that she bought at a dollar store, the artifact of a habit that racked up late fees at several L.A. libraries. Once a book becomes a part of her, she has a hard time giving it back.

“My friends will be, like, ‘You’d love this book. Let me lend it to you,’” she said. “And I’m, like, ‘Listen to me: Don’t.’”

Her first foray into public speaking came even earlier: a second-grade monologue in the voice of Chief Osceola of Florida’s Seminole tribe.

“I’m sure anyone who saw it was kind of aghast at this 15-pound Black girl who was pretending to die on stage as a Native American chief,” she said. “But I think it was important in my development because I really wanted to do justice to the story and bring it to life. It was the first time that I really leaned into the performance of text.”

Gorman is a lot better at it now, but still working on her confidence as a public speaker. In fact, like her predecessor Angelou and the president-elect, she grapples with a speech impediment.

All writers, she said, experience anxiety about the quality of their work. “But for me, there was this other echelon of pressure, which is: Can I say that which needs to be said?” Gorman has labored to perfect sounds most people take for granted. The R has been a particular challenge. The girl who would grow up to perform in front of Lin-Manuel Miranda, Al Gore, Hillary Clinton and Malala Yousafzai struggled for years not to say “poetwy.”

“But I don’t look at my disability as a weakness,” said Gorman. “It’s made me the performer that I am and the storyteller that I strive to be. When you have to teach yourself how to say sounds, when you have to be highly concerned about pronunciation, it gives you a certain awareness of sonics, of the auditory experience.”

Whereas Angelou had strangers at the supermarket inquiring about her progress in the run-up to her reading at Bill Clinton’s inauguration, Gorman has written her poem in pandemic-induced solitude. But the enormity of the task was not lost on her. While writing “The Hill We Climb” — which should take about six minutes to read at the ceremony in Washington, D.C. — the poet listened to music that helped put her “in a historic and epic mind-set,” including soundtracks from “The Crown,” “Lincoln,” “Darkest Hour” and “Hamilton.”

Gorman also wrote her poem while watching pro-Trump extremists storm the U.S. Capitol, a scene she found “jarring and violating” but not surprising. “I think we’d seen the signs and symptoms for a while,” she said.

The attack on Congress made its way into her work — not as a rupture but as a harsh fact of our history. “I wasn’t trying to write something in which those events were painted as an irregularity or different from an America that I know,” said Gorman. “America is messy. It’s still in its early development of all that we can become. And I have to recognize that in the poem. I can’t ignore that or erase it. And so I crafted an inaugural poem that recognizes these scars and these wounds. Hopefully, it will move us toward healing them.”

Gorman, who majored in sociology at Harvard, has spoken up in public forums about a broad range of issues, including racism and police brutality; abortion bans in the U.S.; and the incarceration of migrant children. She is also the first person to announce her intention to run for president in 2036, the first election cycle in which she’ll be old enough to do so. Seeing Vice President-elect Kamala Harris poised to take office has reinvigorated her plans.

“There’s no denying that a victory for her is a victory for all of us who would like to see ourselves represented as women of color in office,” she said. “It makes it more imaginable. Once little girls can see it, little girls can be it. Because they can be anything that they want, but that representation to make the dream exist in the first place is huge — even for me.”

When she’s not watching cooking shows, Gorman copes with isolation by reading books to prepare her for that future. She picked up former President Obama’s “A Promised Land” the day it came out. She’s also reading Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s “Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History,” which interrogates long-standing historical narratives from the Haitian Revolution to the Alamo.

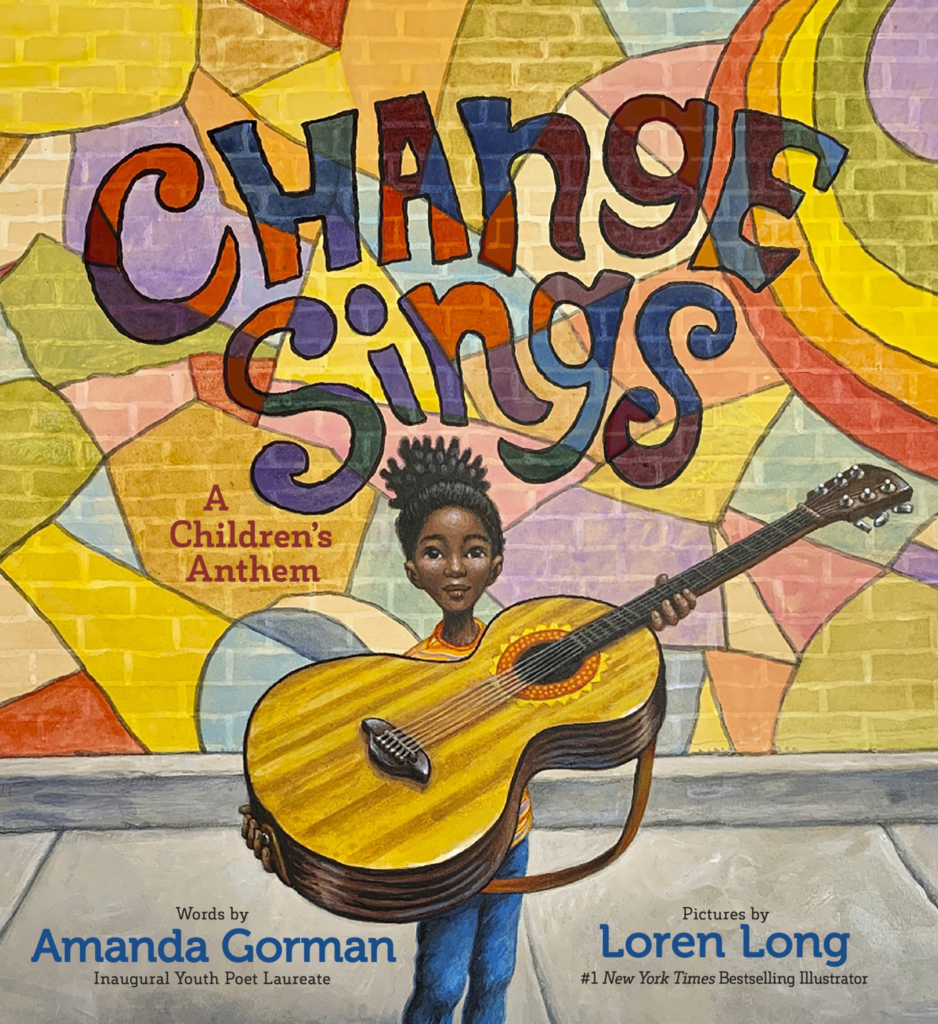

In September, Gorman will release “Change Sings,” the first of two children’s books. The poet says she was driven by the desire to publish a book “in which kids could see themselves represented as change-makers in history, rather than just observers.” It will be illustrated by Loren Long, who created the art in Obama’s “Of Thee I Sing: A Letter to My Daughters.”

On occasion, Gorman ventures beyond her apartment to a hill overlooking Los Angeles. Looking out at the landscape, she’s marveled that “growing up, I was surrounded by so many colors and so many tongues and so many ways of thinking. And it’s very rare that you can have so many of those things in one place.”

“I miss and love everything,” she added. “Everywhere I’ve been and everywhere I have not. Once things are safe, I’m going to spend as much time as I can reabsorbing the city.”

Despite her many accomplishments, Gorman has yet to obtain a driver’s license. But she’s not too worried about it. Her twin sister, she said, will likely “drag me to Disneyland once it’s safe, so maybe she can just drive me around.”