A French World War Two hero who worked as a British agent behind enemy lines had been all but forgotten. But now his story can be told – thanks to a 98-year-old British veteran and a golden engagement ring.

At 15:30 on 9 September 1944, just inside the front gates of the notorious Buchenwald Nazi concentration camp, 16 prisoners of war stood waiting.

All were Allied agents who’d been captured behind enemy lines. Eight of them were Frenchmen working with the UK’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) – Churchill’s “secret army” – and the remainder were British, Canadian and Belgian. Before these men had been caught by the Germans, they had been parachuted into occupied territory to support the Resistance ahead of D-Day.

Earlier that day, their block chief at the camp had been handed a list of their names. Each one had been struck through in red by the Gestapo.

The men had been given the impression they’d been summoned to be interrogated. They wouldn’t necessarily have worried their lives were at risk – they’d been told they were to be exchanged for a group of German officers at some point in the future. But one of the prisoners was suspicious.

“Only little Marcel Leccia, who came from Ajaccio, said, ‘We’re going to be hanged,'” the block chief, a German political prisoner named Otto Storch who worked as a kapo or inmate-orderly, recalled after the war.

Leccia was 33, from a distinguished Corsican Resistance family, and his experiences of war had left him with good cause to be distrustful – he’d ended up in Buchenwald after he was betrayed by a supposed comrade who was secretly working for the Germans.

A British officer who had once trained Leccia in guerrilla combat described him as impulsive and quick-witted, “never lost for words, cheerful, entertaining and very sociable” – as he put it, a typical Frenchman. Another noted his “cynical and imperious” manner. But Leccia had a tender side, too.

During his training, he had fallen in love with a fellow SOE agent named Odette Wilen and the couple had become engaged. So in Buchenwald, before gathering at the gates with the other prisoners, Leccia handed something to Storch. “He gave me his engagement ring,” the block chief wrote in a report.

At the camp gates, according to Storch, the names of the 16 assembled prisoners were read out by an SS officer. Then the inmates were led away two by two, with their hands bound. “We were all very depressed, especially me, as I was well aware of what was to follow,” Storch wrote.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. Elsewhere in the camp, a British prisoner had heard the names of the 16 men being called out.

Until very recently, Marcel Leccia’s name appeared to be fading into obscurity, except among members of his family. He has no known grave. While his name appears on the memorial to the French Section of the SOE at Valençay, France, Britain’s official memorial to the missing at Brookwood Military Cemetery, Surrey, lists him under his training nom de guerre rather than his real name. A plaque close to the spot where he parachuted into France wrongly states that he and his men were arrested there by the Gestapo.

“His story hasn’t been written before, there have just been odd passing references,” says Paul McCue, a military historian who was instrumental in uncovering Leccia’s story. The Frenchman’s decision to entrust the kapo with his engagement ring was key to changing that.

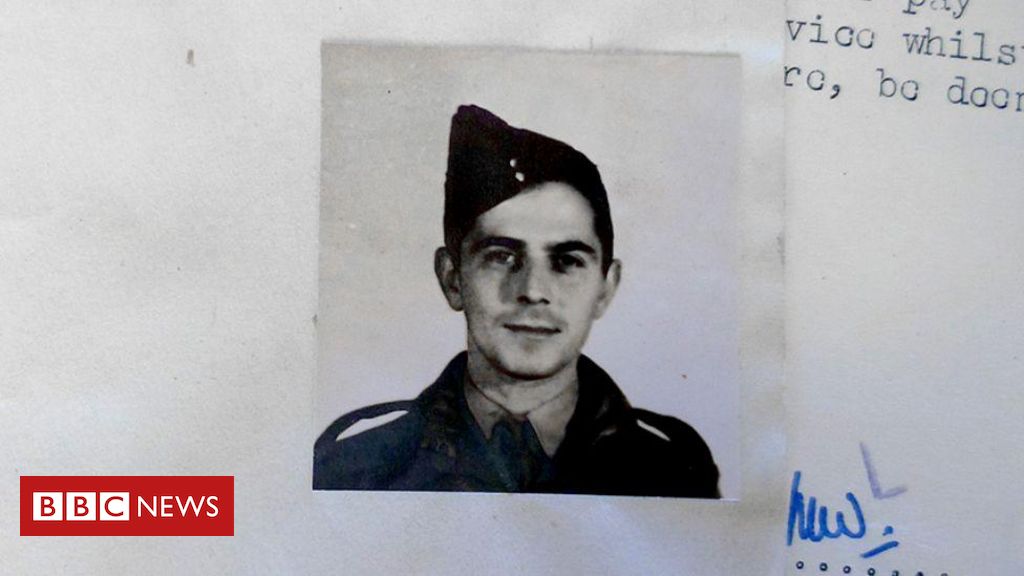

Marcel Mathieu René Leccia was born on 1 January 1911. His father was a colonel in the French army and Leccia was partly brought up in the French-occupied Rhineland, where he became fluent in German. After his national service he worked for a time as a Renault car salesman and married a woman named Alice Beitz – the couple had two children but later divorced. Then in August 1939, with World War Two looming, he was called up to the army as a 2nd lieutenant.

Leccia was awarded the Croix de Guerre medal for the bravery he showed fighting against the invading Germans, but by June 1940 he had been captured. He was taken to Stalag XI-A prisoner of war camp 90km (56 miles) south of Berlin and in 1942, having volunteered for a work party, managed to escape.

After crossing the Vosges mountains, he made it to the city of Limoges in central France, where his family had now made their home and which at that time was in the zone libre, under the control of the collaborationist Vichy regime but unoccupied by Axis forces.

Leccia made contact with an old school friend named Leon Guth. Although Guth was now a police chief working under Vichy, he was sympathetic to the Allied cause. Thanks to Guth’s influence, Leccia was given a job managing a centre for POWs in Limoges – and also acting as an intermediary between Guth and Virginia Hall, the legendary one-legged American-born spy who ran espionage networks in France for the SOE and the US Office of Strategic Services, a forerunner to the CIA.

Hall thought highly of Leccia, referring to him and his friend and comrade Elisée Allard as her “nephews”, and enlisted his help to free a number of captured British agents. However, in late 1942 the Axis powers moved to occupy the zone libre. Knowing the Germans would be looking for her, Hall fled to Spain; soon afterwards, Leccia decided to follow her. After crossing the Pyrenees with Allard he was arrested on a train to Barcelona for not having valid identity papers.

Leccia and Allard spent most of the following year in a series of Spanish prisons and concentration camps. But in September 1943, as General Franco began to rethink Spain’s de facto support for the Axis powers, the two men were released. With Hall’s help they crossed the border into Portugal and made contact in Lisbon with the British Consul, who arranged for them to be flown to Bristol on 10 October.

The two Frenchmen were taken to MI5’s London Reception Centre, a sprawling ex-asylum in Wandsworth, to the south of the city. During the war, escapees from occupied Europe were sent here for security clearance. The intelligence service was on the lookout for enemy spies attempting to make it into the UK – and also used the centre for talent-spotting potential agents to serve Britain.

Leccia passed on a number of complaints from Hall about the supplies that SOE agents in France were sent from the UK. Among the gripes were that clothes given to agents were often too new and cut in styles that looked unusual in France and banknotes were consecutively numbered. He also complained that some agents, completely out of keeping with French custom, smoked pipes in public.

Leccia impressed his MI5 interrogator, who described him as “intelligent and a man of initiative”.

He was soon recruited into the SOE – the secretive agency set up by the British to organise, arm and train resistance movements in occupied countries. To protect his family, he was given the training name “Georges Louis” along with the service number 309883.

He was sent to training schools around mainland Britain and earned his parachute “wings”, learned about industrial sabotage and was taught how to operate telecommunication equipment. His assessment concluded: “This man is a born leader. He is sure of himself… he should prove capable of doing very useful work.”

In Beaulieu, Hampshire, Leccia studied alongside a 24-year-old woman named Odette Wilen. Born in London to a French mother and a Czech father, her Finnish husband, an RAF pilot instructor, had been killed in an accident the previous year.

“She was young, she was recently widowed, still full of life, but desperately wanted to contribute in a positive way to the war effort,” says Miguel Strugo, her son. A skilled linguist, she was training to be a wireless operator. She and Leccia fell in love.

Then it was time for Leccia to return to France. He took on his old identity again, but now he also had the code name “Labourer” – the name by which SOE headquarters would know him and the small team he would lead – as well as the field name “Baudouin”, which the local Resistance would use.

Their mission included orders to destroy railway lines on the outskirts of Tours, in the Loire valley, and blow up a chateau nearby that was being used as a base by the German military. On the night of 5-6 April 1944, Leccia and his Labourer network were dropped by parachute near the town of Châteaumeillant, 170km (105 miles) south-east of Tours, and were met by a reception committee of the local Armée Sécrète.

The Labourer team – Leccia, Elisée Allard and a radio operator named Pierre Geelen – were initially housed in a village near their landing site, but they would need to find accommodation closer to their targets.

As Leccia was trying to arrange this, with the help of someone referred to in SOE documents as “Pebert” or “Lance” – thought to be a young medical student called Rene Lavaud – Odette Wilen was parachuted in. It had been intended that she would serve as a radio operator for another network, but her training had been too rushed – “so they decided not to run the risk and that she should be a courier instead”, says Strugo. She joined Labourer in this capacity.

Lavaud suggested that the group should travel with him to Paris, and Leccia agreed to this, but he told Wilen to stay where she was until the new base was set up. It was a decision that would save her life, as Lavaud was secretly working for the Germans.

Records state that he drove the Labourer team straight to the Cherche-Midi, a former French military prison in Paris, where the Germans had cells waiting for them. (According to later reports, Lavaud appears to have fallen out of favour with his German handlers and was shot by the Gestapo.)

Leccia spent 52 days in 84 Avenue Foch, headquarters of the SS counter-intelligence service, where interrogations could be brutal. Then, on 8 August 1944 he and the rest of Labourer were put on a train to Germany as part of a group of 37 agents. Also on board were two legendary SOE officers – Wing Cdr FFE Yeo-Thomas, nicknamed “The White Rabbit” by the Gestapo, and Sqn Ldr Maurice Southgate. On 17 August they arrived just outside Weimar at Buchenwald – the first and largest Nazi concentration camp within Germany’s pre-WW2 borders.

More than 56,000 died there – Jews, prisoners of war, political prisoners, Poles, Roma, Freemasons and others considered undesirable by the regime, including criminals, sexual “deviants” and people with mental and physical disabilities. Leccia and the other SOE men were housed in Block 17, which was reserved for special prisoners and separated from the rest of the inmates’ accommodation by barbed wire.

It was three weeks and two days after his arrival that Leccia was summoned to the camp gates to be murdered.

“I think he was quite a feisty little guy – I wouldn’t have necessarily said he was a gloom and doom merchant,” says McCue. “But he was one of the few, if not the only one, who said, ‘This is the end of it.'”

Camp records say they were executed three days later, on 12 September – hanged, with wire around their necks, from hooks in the walls of the mortuary. It’s likely that their bodies were disposed of in one of the camp’s crematoriums. A second group of 14 Allied personnel, including another four SOE agents drawn from the original group of 37 prisoners, were shot the following month.

After Leccia’s death, Col Maurice Buckmaster, the head of the SOE’s French section, wrote – some might suggest uncharitably – in the Frenchman’s file: “Proved by his early career that he was an ace at this sort of work. Did he become too cocksure? And perhaps a trifle careless? Engaged to Odette Wilen. A tragedy for her.”

Two years after the death of her first husband, Wilen had now lost a fiancé, too.

As Leccia and the other SOE men were led away to their fates, an English airman watched them from a distance – the same prisoner who had taken notice when their names had been read out over the loudspeakers.

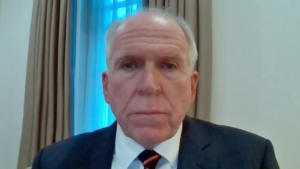

Stanley Booker, who was born in Gillingham, Kent, had been the 22-year-old navigator in an RAF Halifax bomber that was shot down over France just before D-Day. He’d been sheltered by the Resistance, but a plan to bring him home was foiled when someone betrayed him to the Gestapo.

Booker was one of 168 Allied airmen in Buchenwald. As a result of the bombing campaign waged against Germany, their captors were strongly hostile towards them, referring to them as the Terrorfliegeren or “terror-fliers”. Their presence in the forced labour camp was contrary to the Geneva Convention – in order to get around the requirements of international law to treat them humanely, they were not officially categorised by the Nazis as prisoners of war, and their documents were stamped “not to be transferred to another camp”.

Booker, like his comrades, assumed all this meant he would never make it out alive. “It was our death warrant,” says Booker, now 98.

He was brutally interrogated in Paris and shortly before the city was liberated he too was put on a train to Buchenwald, arriving five days after Leccia and the other 36 SOE men – though both groups of prisoners were only vaguely aware of the other’s presence.

On 9 September, as the 16 names were read out over the loudspeaker, Booker listened carefully. Most were French, but some sounded British – “there was a Mac-something,” he recalls. That was most likely a Canadian captain, John “Ken” Macalister.

Booker says that along with two or three others, he dashed to the gates to see what was going on. “There was the awful spectacle of them all gathered outside,” he recalls. He watched as they were led across the courtyard into a building. “They walked in, marching through the doorway. And we didn’t see them again.”

Booker was luckier than Leccia. Buchenwald’s communist underground managed to smuggle out word of the presence of Allied airmen in the camp and the German air force, the Luftwaffe, was made aware of this. The Luftwaffe – which had an interest in ensuring that captured airmen were treated in accordance with the Geneva Convention – petitioned for them to be moved.

Soon they were transferred, as official prisoners of war, to Stalag Luft III in Poland- the setting for the 1963 film, The Great Escape. Booker was then sent to another PoW camp near Berlin, where he was held captive by the Red Army before being freed.

After the war, Booker remained with the RAF, moving into intelligence work. He relocated with his family to Germany and was involved in the Berlin Airlift, the multinational effort to supply the city by air during a year-long Soviet blockade. But he remained haunted by his wartime experiences.

After he retired with the rank of squadron leader, Booker was awarded the MBE for his services to British intelligence. In retirement he devoted himself to campaigning for the British servicemen from the RAF and SOE who were sent to Buchenwald without the official status of prisoners of war and whose suffering had been overlooked.

For instance, Booker had not received an RAF salary during his time at the camp, and though the sum was negligible, he lobbied for it to be symbolically issued as back pay. In 2010, thanks to his efforts, two memorial plaques were finally unveiled at the site to its British, French and Belgian intelligence service inmates. And earlier this year, already 98, he was awarded the Légion D’honneur – France’s highest military or civil honour.

Booker never forgot about the SOE agents whose names he had heard called out on 9 September 1944 before their execution.

“My father was so touched by their story,” says Pat Vinycomb, his daughter. “That was a huge driver for justice for these unknown men, who were often operating under a number of aliases and were murdered.”

During the 2020 coronavirus lockdown, Vinycomb was going through boxes of her father’s papers and writing a book interweaving her father’s experiences in Buchenwald with the stories of other RAF and SOE personnel at the camp. During her research, she’d managed to unearth documents kept by the Gestapo. “The Germans were very good at keeping records,” she says.

She’d also happened upon the report written after the war by Otto Storch, the block chief, about the execution of the SOE men, including Leccia, and turned for help with translation to Paul McCue, a trustee of the Secret WW2 Learning Network, an educational charity that aims to raise the profile of Allied special operations during the war.

“When Paul got the papers translated, he suddenly realised the significance of the engagement ring,” says Vinycomb.

McCue contacted the Buchenwald Memorial – a museum that now stands at the site of the camp. “They confirmed: yes, they still had the ring, and sent me a photo of it,” he says.

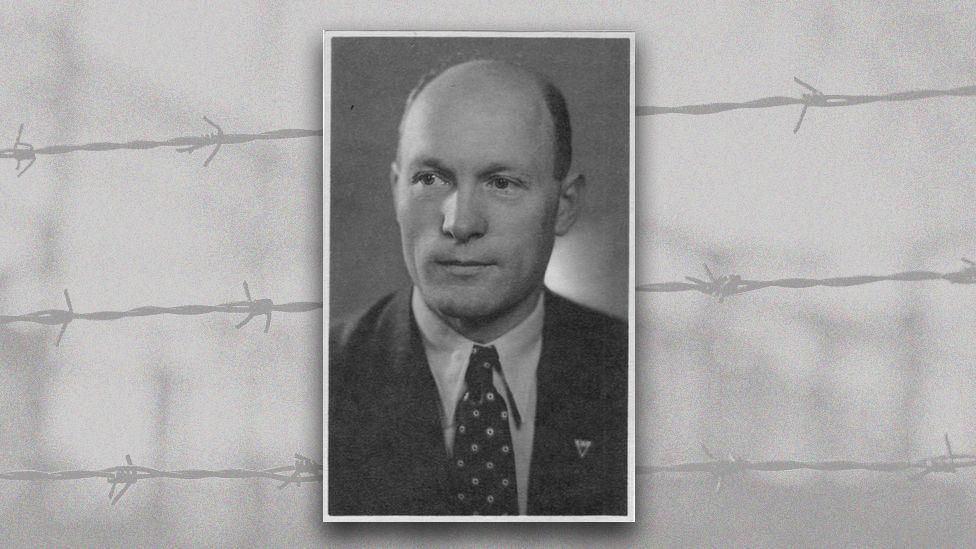

According to Holm Kirsten of the Buchenwald Memorial, Storch had held on to the ring after the war. Before his death in 1970, he gave it to another former inmate, who in turn donated it to the Memorial at some point in the 1980s and from 1995 it was put on display in the museum.

McCue wondered if Leccia’s descendants were even aware of the ring. But he still knew relatively little about the Frenchman – there wasn’t much online, except in passing references in obituaries to Wilen, who died in Buenos Aires in 2015 at the age of 96.

After Leccia’s capture she had escaped across the Pyrenees, where she met a Spanish Republican named Santiago Strugo Garay, who led the Spanish escape network. After the war he tracked her down in London and married her. Then the couple moved to Argentina.

According to Miguel Strugo, her son, she had separately got in touch with the Buchenwald archivists shortly before her death. “One day she told me about the ring, and that it was in the Buchenwald museum – I was incredulous. I couldn’t believe it,” says Strugo. “I thought that when the prisoners were being executed, they’d have all their goods robbed.”

McCue looked up Leccia’s SOE personnel file at the National Archives in Kew, which contained a wealth of biographical information about his wartime exploits.

It became apparent that the SOE memorial at Brookwood Military Cemetery, Surrey, listed Leccia not under his real name but as “Georges Louis”, his training name. After McCue contacted the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, they agreed to update their website to give Leccia’s correct name, and a spokesman says specialist stonemasons will update the memorial “soon”.

McCue then put out feelers through French historians and worked his way through telephone directories looking for relatives of Leccia.

Eventually he found a man named François Leccia, whose grandfather and namesake – a Resistance fighter – had assisted Marcel Leccia in the days after he parachuted back into the country in April 1944.

While Marcel’s story may not have been widely known, it had been kept alive within the family – not least because his sister Mimi only died in 2018 at the age of 106.

“I have always heard about cousin Marcel of the British secret service, hanged in Buchenwald,” says François, who lives in Gabon, West Africa, where he runs a shipping company. He told McCue some of his relatives had been campaigning for a street in Corsica to be named after Marcel. François said he was also in touch with Jean-Marc, Marcel Leccia’s grandson.

McCue asked François Leccia if he felt the ring should be returned to the family. But François and Jean-Marc were in agreement – it should stay where it is.

“I think it is right that the ring must remain at the Buchenwald museum in order to keep the memory alive, rather than let it slip into oblivion at the bottom of a drawer,” says François.

And so it has already proved. The ring prompted Booker, McCue and Vinycomb to revive the memory of an extraordinary life cut short.