Explore the fascinating intersection of portraiture and labor

Dorothy MossSeptember 5, 2024

The American worker and the American art museum have a storied history. Viewing portrayals of workers through the lens of artist as worker reveals a relationship between the artist and subject often lacking in formal, commissioned portraits, where business and social dynamics may create a distance. In viewing portraits of workers as visualizations of shared experience and understanding, the questions that emerge are twofold: To what extent has the cultural status of workers and artists aligned over time? And how has the role of the art museum factored into broader perceptions of the cultural value of the American worker?

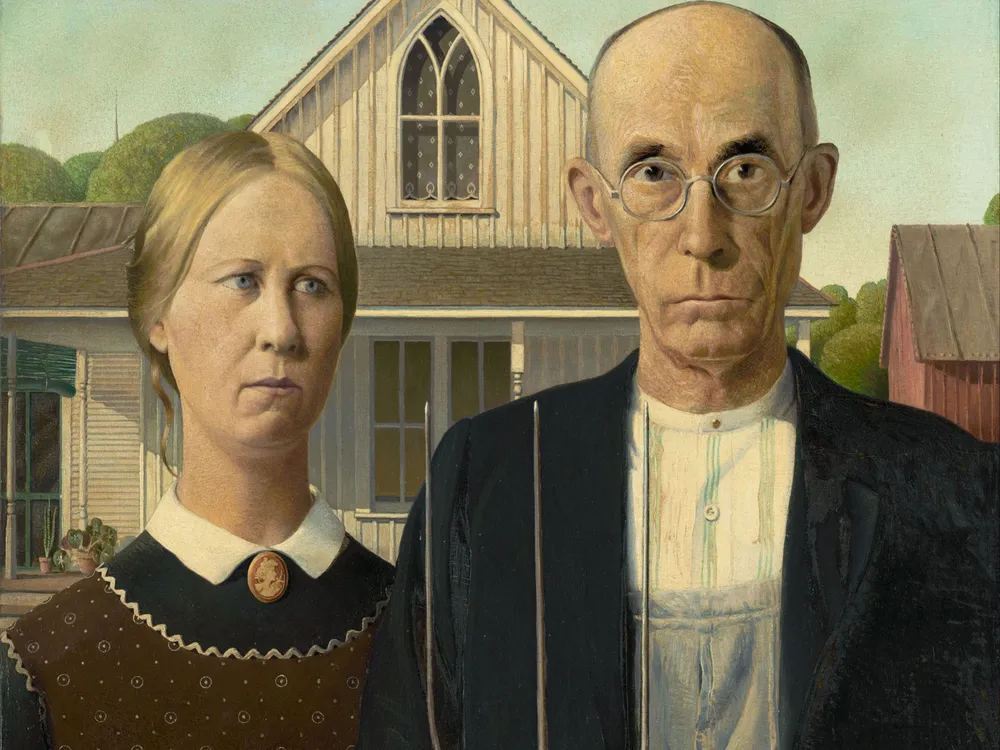

Exploring the relationships among the American art museum, the artist, and the worker reveals a depth of connections. An important thread that runs through artists’ examinations of work and identity in portraiture is the use of appropriation, or quoting earlier artists’ portrayals of laborers, to assert the artist’s own identity as a cultural worker. Gordon Parks, Hung Liu, and Ramiro Gomez have used this method to address the invisibility of those workers and artists whose labor goes unappreciated or unrecognized. In the process, their portrayals acknowledge a history of workers’ lack of agency and reclaim workers’ humanity. By quoting source material created by mainstream artists—mainly white males—and reinventing and reimagining iconic images while metaphorically inserting their own stories into those images, they have recognized the shift in the relationship between the artist and the worker over time, both in the context of the work’s institutional presentation and in terms of race, gender, and cultural affiliation.

In late-nineteenth-century America, when museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art were still new and administrators and board members were defining their missions, workers were not always welcomed in these “sacred” cultural spaces. An incident at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1897, involving a plumber who entered the museum, incited “flaming headlines and startling pictorial protests.” The New York Times reported that the plumber, who was on a break from a job on Fifth Avenue, was asked to leave the building on the grounds that he was wearing overalls, which were considered offensive in the context of the museum. The news of this episode spread across the country. One critic questioned whether the plumber had been asked to leave because he violated a clothing policy or because of his status as a laborer. According to the Milwaukee Journal, museum director Louis Palma di Cesnola claimed that in his seventeen years at the institution “not a single individual in overalls has been allowed to look at the pictures” and that “the rules forbid drunken or disorderly persons from being allowed in the museum, and that a man in working clothes is as bad as either.” In a biting call to action in the Butte (MT) Weekly Miner, an outraged writer commented: “The workman who desired to visit the museum is not charged with being dirty. There was not a word to the effect that he was not gentlemanly in his demeanor. The only crime which he committed was to wear overalls and to attempt to look upon the works of art, most of which were produced by men who wore homespun.” The writer continued, “The laboring men of the city of New York should make an example of General [di] Cesnola and his hair-brained subordinates. Any man so guilty of so gross a violation of the spirit of American institutions should be considered a political issue until his complete obliteration from official life is effected.”

This occurrence provides a picture of the uneasy relationship between the worker and the art museum at the end of the nineteenth century. It was an era in which mass reproduction raised new questions among the American public about the role of art in education and in the domestic and public spheres. It was also an important period in the development of American art, one that art historian and Smithsonian curator of prints Sylvester Rosa Koehler described in his 1886 publication American Art as “a period of awakening, of high hope, and of honest endeavor.”

Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, discussions about the role of the artist, the art museum, and the worker would concern museum officials and board members, who sought to achieve cultural and social improvement through education in museums. In the process of coming up with an effective strategy and in determining who would benefit from such an education, museum administrators contended with what historian Paul DiMaggio describes as the “tension between monopolization and hegemony; between exclusivity and legitimation.” In other words, they wanted to maintain cultural control while influencing broad audiences. As officials grew more comfortable with the use of museums as educational laboratories through the exhibition of “true” art, they began to place increasing emphasis on codes of behavior in the museum and on the importance of original artworks.

The cultural distinction of the artist as worker in American industrial and postindustrial society is seen in art created in response to the changes in attitudes toward authorship. As Julia Bryan-Wilson has pointed out, following Michael Baxandall’s seminal work Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy (1972), there has been a history of separation between craft and “true” labor in Western art since the Renaissance. At that time, the notion of the “author” of a work of art emerged, and objects that were created by hand were no longer attributed to anonymous workers but to the people who made them.

American artists have identified with workers and at times organized labor since the late nineteenth century. The many groups and organizations that have formed over the years aligning artists with workers attest to this commitment. As Bryan-Wilson has described, examples persist of individual artists or organized groups of artists, often drawing on Marx, who have insisted that their work was a form of labor—whether following the craftsmanship model of William Morris and the Art Workers Guild that grew from it in 1884 or the later example of the Mexican muralists of the 1920s, who founded the Revolutionary Union of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors. In reaction to the Great Depression, the numerous artists who were influenced by socialist ideology and the labor movement organized themselves as cultural workers, following the strategic tactics of the trade unions. By the summer of 1933, a small group of artists had formed the John Reed Club. During that summer, the artists associated with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) identified with the laborers they depicted and created images that were not only about labor but also were easily relatable to laborers in narrative and form. The founding of the Artists’ Union in the 1930s was key to artists’ perception of themselves as workers. As Andrew Hemingway suggests, “It was this collective enthusiasm and the identification with other workers that made union members such an active presence in demonstrations and on picket lines.”

Aside from membership in organizations, artists also took typically blue-collar jobs to support themselves. For example, Honoré Sharrer’s experience as a welder in shipyards in California and New Jersey during World War II deeply informed her art, which reflects her commitment to the working class, especially her Tribute to the American Working People (1943). While artists drew on lived experiences of working in their choice of process, form, and subject matter, they also used their materials and processes to critique work and working. As Helen Molesworth has argued, in the period following World War II, “the concern with artistic labor manifested itself in implicit and explicit ways as much of the advanced art of the period managed, staged, mimicked, ridiculed, and challenged the cultural and societal anxieties around the shifting terrain and definitions of work.” An example of this is Robert Morris’s Box with the Sound of Its Own Making, a minimal sculpture that is essentially a portrait of work—or a portrait of the artist working—consisting of a wooden box with a tape recording of the sounds of sawing and hammering. As Morris and other artists of his generation experienced the change from a manufacturing to a service economy in the 1960s and 1970s, artists and critics took on the role of “art workers” and understood the practice of making art in a variety of mediums, including performance, as a form of social critique and commentary about the relationship between art and work.

Women artists particularly focused on performance art as a strategy to comment on the gendered division of labor from a feminist point of view and to ask audiences to consider the cultural value of domestic work. Among those who have been pioneers in addressing work from the feminist perspective through performance is Martha Rosler, who throughout the 1970s took as her subject matter traditional forms of women’s labor and domesticity. For example, her Super 8 film Backyard Economy I and II (1974) shows her performing the domestic labor of watering plants, mowing the lawn, and hanging laundry to dry on a clothesline. She enacts these monotonous duties in the safe, comfortable context of her own sunny backyard, which projects a seemingly ideal environment. Through the peaceful beauty of the setting, she turns these chores into works of art. As Molesworth asserts, “Like many feminist artists of her generation, Rosler insists that these everyday jobs perform double duty inasmuch as they stand as both housework and artwork.” Cindy Sherman is another woman artist who has explored her persona and identity as an artist. In Scale Relationship Series—The Giant, made during what Eva Respini has described as Sherman’s “early days of experimenting with the plasticity of identity,” Sherman presents herself as the folklore hero Paul Bunyan, the lumberjack with superhuman strength. While the project was meant to explore scale and satirize “the myth of the proud American ‘big Man,’” there is a sense of identification through transformation of the self into an alter ego.

Male artists during the 1960s and 1970s also employed the strategy of performance to address their identity in terms of work. For example, Frank Stella—who, like many artists, at times adopted an executive model and employed assistants— presented himself as a working-class person both in his outward appearance and in the tools and materials he chose to use, such as house paints. He famously said, “It sounds a little dramatic, being an ‘art worker.’ I just wanted to do it and get it over with so I could go home and watch TV.” This comment points to the notion of the artist as existing to create a commodity, as described by Marx: “The worker works in order to live. He does not even reckon labor as part of his life; it is rather a sacrifice of his life. It is a commodity which he has made over to another. . . . What he produces for himself is not the silk that he weaves, not the gold that he draws from the mine, not the palace that he builds. What he produces for himself is wages.”

Throughout the 1960s, many of the most prominent artists in New York presented themselves as workers in their appearance as well as in their personal lives, doing “odd jobs” that sometimes inspired their conceptual artwork. Dan Flavin worked as a mailroom clerk at the Guggenheim Museum and as an elevator operator and a guard at the Museum of Modern Art. His 1960 portrait Gus Schultze’s Screwdriver (to Dick Bellamy) was inspired by his friendship with a fellow MoMA staff member and dedicated to an art dealer. It features Schultze’s actual screwdriver attached to the surface of the painting. As a conceptual portrait, it pays homage to those who exist behind the scenes of a museum, the wall painters, maintenance workers, and dealers. In a letter housed in the Archives of American Art, Flavin writes of another experience as a museum guard, this time at the American Museum of Natural History: “Day by day, I filled my notebook with diagrams for that fall. My first black icon with electric light emerged that December.” Reflecting on that experience, Flavin writes, “I crammed my uniform pockets with notes for an electric Light art. ‘Flavin, we don’t pay you to be an artist,’ warned the custodian in charge. I agreed and quit him.”On the one hand, this anecdote demonstrates that Flavin’s custodial job inspired an important body of work in his career and in the history of art, and it testifies to the synergy between his identities as artist and worker and the ways the two are interrelated and ultimately integral. On the other hand, Flavin’s recollection points to the separation between art and work and the struggle that artists supporting themselves through day jobs contend with in reconciling their identities as artists and workers.

It is that sense of straddling identities that characterizes the identification of artist and worker in the quotations or appropriations of Gordon Parks, Hung Liu, and Ramiro Gomez, artists who have worked as laborers and discussed their art in terms of their autobiographical connections with the working subjects of their portraits. In On Longing, cultural theorist Susan Stewart describes the significance of the act of “quotation” as a form of “interpretation” of the “original.” She explains that while granting the initial source a sense of “authenticity,” quotation also creates opportunities for new interpretations of the original material. By studying themes of work in historic or iconic images by other artists and creating new images that reference the past, Parks, Liu, and Gomez extend earlier discussions about the role of the artist, the status of work, and the museum’s role in shaping perceptions about work and workers.

Read more in The Sweat of Their Face, which is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from The Sweat of Their Face: Portraying American Workers by David C. Ward and Dorothy Moss © 2017 Smithsonian Institution