Lessons from the slave trade and the Holocaust by

Summary.

Some multigenerational companies or their predecessors have committed acts in the past that would be anathema today—they invested in or owned slaves, for example, or they were complicit in crimes against humanity. How should today’s executives respond to such historical transgressions? Drawing on her recent book about the effort by the French National Railways to make amends for its role in the Holocaust, the author argues that rather than become defensive, executives should accept that appropriately responding to crimes in the past is their fiduciary and moral duty. They can begin by commissioning independent historians, publicly apologizing in a meaningful manner, and offering compensation on the advice of victims’-rights groups. The alternative is often expensive lawsuits and bruising negotiations with victims or their descendants.

In 2002 the executives of CSX, a freight railway company whose origins lay in the early 1800s, received unexpected news: The company was being sued in a federal district court in New York as part of a class action lawsuit filed on behalf of all living descendants of enslaved people in the United States.

The lawsuit, which also included FleetBoston Financial (now part of Bank of America) and Aetna, sought unspecified damages, compensation for unpaid forced labor, and a portion of the profits resulting from that labor. The plaintiffs cited CSX’s use of enslaved people to construct its railways, FleetBoston’s connection to an earlier bank founded by a man who owned ships that transported enslaved people, and an Aetna predecessor’s practice of “[insuring] slave owners against the loss of their human chattel.”

The accusations were all accurate, and they raised an important legal and moral question: Should a long-established company be required to atone for the atrocities of a bygone era? John W. Snow, then the chairman and CEO of CSX (who later served as secretary of the treasury under George W. Bush), thought not. The company issued a statement arguing that although slavery was tragic, the case was “wholly without merit.” A spokesperson, Kathleen A. Burns, chastised the plaintiffs for trying to hold today’s employees and shareholders accountable for ills more than a century old. The court dismissed the case without addressing the merits of the claim, arguing that the plaintiffs could not prove their direct personal connection to those affected.

Legally, the judge’s decision was unsurprising. U.S. courts tend to rule against plaintiffs seeking reparations from corporations for historical crimes, and the International Criminal Court does not try cases involving corporations. But the legal and reputational risks to companies from their long-past activities are growing, as large portions of society push for what they see as an overdue reckoning. Schools are being renamed, mascots are being discarded, and statues of historical figures that only a few years ago barely drew a glance are being toppled. Businesses face scrutiny over the origins of wealth and how they may have exploited people to enable their current profitability. Social media makes it easy for activists to publicize criticism, organize boycotts, and take other actions.

Ultimately, law follows public opinion, and legislatures are unlikely to keep laws on the books that ignore this moral turn. In a comprehensive study of corporate accountability claims for mass atrocities around the world, Oxford University’s Leigh Payne and colleagues found that although legal impunity prevails, calls for atonement from growing portions of civil society are likely to change the landscape in the coming years.

When confronted with what seem like antiquated claims, many executives become defensive: After all, they had no personal involvement in the crimes committed.

As an assistant professor of negotiation and conflict management at the University of Baltimore, I study the role of businesses in mass atrocities and their attempts at making amends. I’ve seen firsthand how executives can be blindsided by revelations of their distant predecessors’ transgressions and how their most common reaction—defensiveness—almost always backfires. I recently published Last Train to Auschwitz: The French National Railways and the Journey to Accountability, about one of the most high-profile legal and public relations disputes in French history: the effort by survivors of the Holocaust to force the French National Railways (SNCF) to atone for its role in transporting tens of thousands of Jews and other minorities under horrific conditions toward death camps in Poland. Drawing on this and other cases, I’ve collected best practices for multigenerational companies taking a proactive approach to addressing the dark chapters of their history.

French Railways’ Checkered Past

In the late 1980s the SNCF was a darling of French industry. France’s first high-speed rail line had opened in 1981 and, along with the Japanese rail system after which it was modeled, was the envy of the world. Among the French public, the SNCF had long enjoyed its role as a bright spot in the country’s mid-20th-century history. During World War II a small number of brave railway workers had sabotaged the country’s trains on D-Day as part of the Resistance, earning the SNCF France’s highest medal of honor in 1951. But many people in France and elsewhere knew another part of the SNCF story: During the war, French drivers and railway operators had transported Jews in packed cattle cars with barely any light, food, or water to the German border, where they were transferred onward, often to Auschwitz.

In the early 1990s the French Holocaust survivor Kurt Schaechter secretly photocopied thousands of documents from SNCF archives proving that the train company had played a material role in the deportation of 76,000 Jews from France to death camps. Though evidence of the SNCF’s participation in this crime against humanity was irrefutable, its executives spent years defending the company. Soon after he was appointed its chairman, in 2008, Guillaume Pepy echoed many of his predecessors when he told a radio interviewer that the SNCF’s job during the war was “simply to make the trains run”—the implication being that the company shouldn’t be held accountable for what they carried. Executives also highlighted material losses during the German occupation—painting the company as a victim.

Holocaust survivors turned to the courts and the media. Schaechter had filed the first lawsuit in 2003, asking a symbolic one euro in damages. But others followed with claims for larger amounts. The legal battle eventually spilled over to the United States, where survivor groups filed reparations lawsuits and lobbied for laws that would create barriers to the SNCF’s operations there.

For the railways, resisting accountability proved almost as expensive as accepting it. A multinational legal battle lasted almost two decades, running up enormous fees. From 2012 to 2014, at the height of the conflict, the SNCF spent roughly $1 million a year on lobbying in the United States. That dropped to $90,000 in 2018, after the conflict subsided. Throughout, executives faced bruising encounters with the press, angry plaintiffs, and their supporters. At one point they felt that the reputational damage in the United States was so bad that the SNCF should pull its business from that country entirely. Eventually the company took a number of steps to atone for wartime crimes and mend relations with much of the French Jewish community and some of its diaspora. But in 2015 an exhausted Alain Leray, who served as CEO of SNCF America during part of the conflict, told me that in retrospect, it probably would have been easier to settle and pay the victims when the lawsuits began.

I have often asked myself what can be done to break the cycle of pain that accompanies such ordeals. It is a double tragedy when accusers and accused cause one another further damage following a historical atrocity. The answer begins with companies accepting responsibility and proactively trying to make amends. Through my work I have discovered several ways that executives can offer a less-damaging and more restorative experience for everyone involved—the survivors and their descendants and the executives, employees, customers, and shareholders of today.

Accept Responsibility

To appropriately respond to historical crimes, corporate leaders must accept that doing so is their fiduciary and moral duty. When confronted with what seem like antiquated claims, many become defensive: After all, they had no personal involvement in the crimes committed, and many companies profited from slavery, colonialism, and genocide. Why should only the few that remain from that bygone era carry the burden of atoning for those sins?

Courts have been sympathetic to that view. But lawsuits can be damaging even if the judge’s ruling is favorable. When she filed a class action lawsuit against the SNCF on behalf of 600 litigants in 2006, the New York lawyer Harriet Tamen knew that the company was protected by the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act. But she used the doomed lawsuit to attract media attention. It worked: The scrutiny helped activists persuade U.S. legislators to draft bills creating barriers to the SNCF’s bids for rail projects.

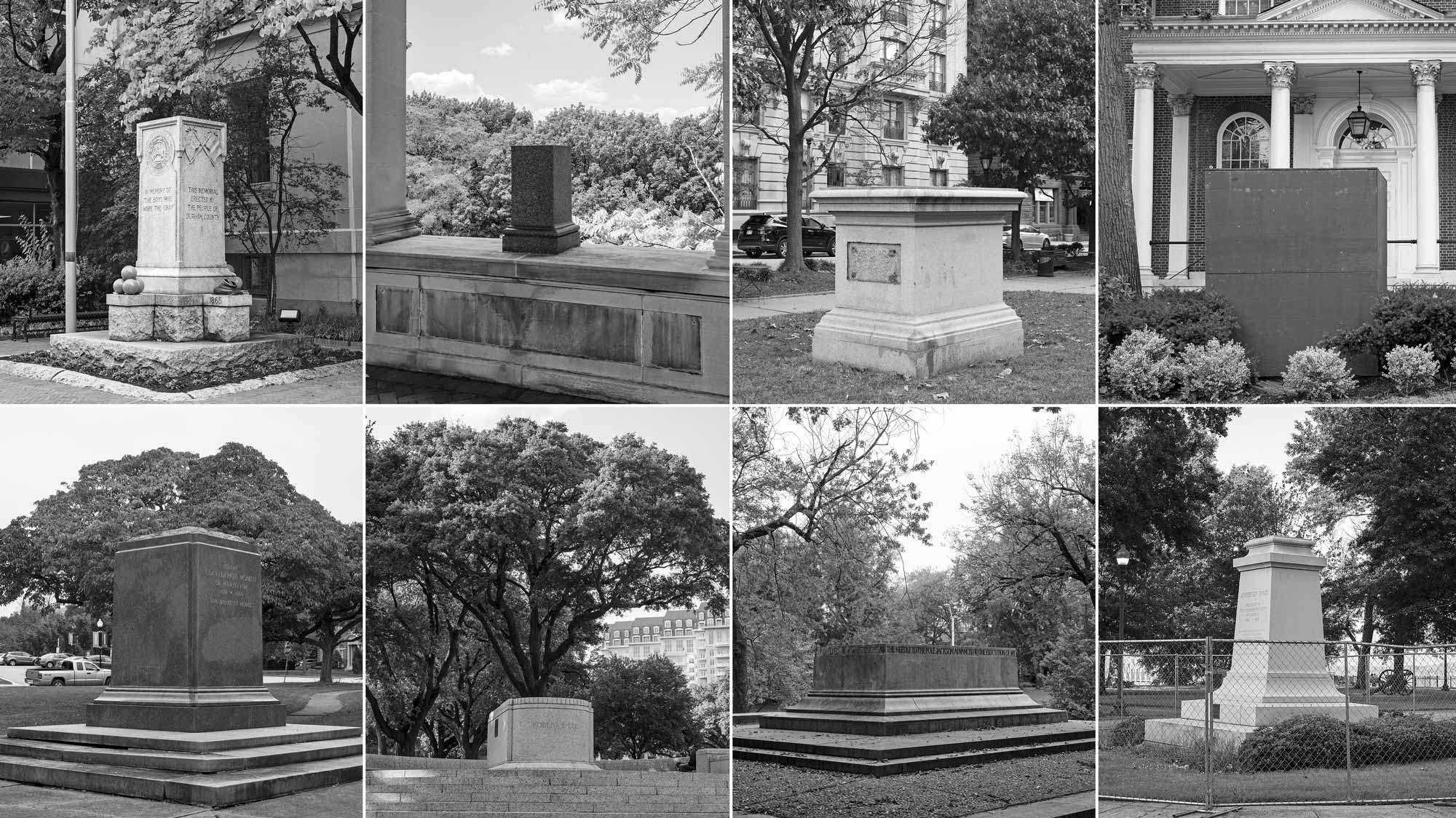

Matthew Shain’s project “Post-Monuments” contemplates the legacy and removal of Confederate monuments across the United States in the hope that the resulting vacancies will provide space for contemplation of our historical narrative.

Evasion almost always backfires for corporations. Refusing to address unatoned-for crimes looks like complicity. Denial of responsibility in the face of legitimate accusations may give executives the appearance of supporting the actions of their predecessors. Evasion also delegitimizes the emotional wounds of victims’ descendants, who in response often mobilize and rally public support against both the original crime and the contemporary dismissal. Finally, it can take a toll on employees, who are increasingly demanding that their employers live up to pledges of diversity and inclusion by acknowledging their role in historical oppression. In 2020, for instance, Lloyd’s of London, the 335-year-old insurance company, responded to long-standing pressure from Black employees to better understand and make amends for the company’s sale of insurance policies on enslaved people and the ships that transported them.

So how can executives calm rather than inflame tensions? They can take their cues from the field of transitional justice, which develops interventions following mass atrocities. After World War II, practices emerged from that field to support nations transitioning from tyrannical regimes to democratic ones. Those practices include efforts at transparency (through the proactive investigation of one’s past), compensation, apology, commemoration, dialogue, institutional reform, and victim services. They have already been employed across the world, from Rwanda, Argentina, and Sierra Leone to the United States, where transitional justice commissions have addressed abuses such as Japanese internment during World War II, the mistreatment of indigenous peoples, and the use of torture in the war on terror. Increasingly these commissions include corporate actors: Since the 1980s more than 20 truth commissions in 20 countries have involved companies’ representatives.

Investigate Your Past

Ideally, long-standing companies will engage in internal research to identify shameful historical episodes themselves—before survivors or descendants call for justice and set senior leaders on the defensive. SNCF executives undertook no such research and thus were unprepared when Schaechter’s documents became public. Once it was clear that the scandal wasn’t going away, the executives did what they should have done before Schaechter’s revelations: They hired a historian to sort through the company’s wartime archives and make the findings public. They also opened the archives to anyone interested in conducting research. They formed a commission for historians, archivists, company representatives, and some survivors to discuss a more accurate account of the SNCF’s past. The pivot to this understanding of its wartime history was at times poorly handled. For instance, the company invited only five survivors to the 50-person launch of the report. But it was a start.

Apologies land best with affected communities when they are issued without prompting. Corporate sincerity will always be questioned, but proactive statements fare better.

Historical transparency should extend even to materials traditionally used for marketing and promotion, such as About Us pages on company websites. Consider the differing approaches to slavery-related transgressions taken by two Alexander Brown & Sons legacy companies. Alexander Brown, a linen auctioneer from Ireland, emigrated to the United States in 1800 and soon transitioned to cotton. He and his sons expanded the company into banking. Alex. Brown spun out of Alexander Brown & Sons, merged with Bankers Trust in 1997, and was acquired by Deutsche Bank in 1999 and then Raymond James in 2016. Today its home page displays a timeline beginning in 1800, when the company became the world’s first investment bank. The timeline glosses over the fact that this form of banking was created to provide funds supporting the cotton industry and its enslaved labor. The banking firm Brown Brothers Harriman (BBH), another legacy company, offers a more robust account. Its timeline begins by acknowledging that “there are also aspects of our history that we are not proud of and reflect on with deep regret, among them Brown Brothers & Co.’s active participation in the global cotton trade of the early 19th century that relied on the abhorrent practice of slavery.”

Apologize and Make Public Statements

Apologies land best with affected communities when they are issued without prompting. Corporate sincerity will always be questioned, but proactive statements fare better. Consider JAB Holding, which has controlling stakes in household names such as Krispy Kreme and Calvin Klein. The company is owned by the Reimanns, Germany’s second-richest family. In 2016 the economic historian Paul Erker started work to help the Reimanns better understand the family’s activities during the Nazi years. His discoveries were horrendous. The founders of JAB Holding had enthusiastically supported Hitler, and their company used forced labor during the war.

Shortly after learning of the findings, in 2019, Peter Harf, a managing partner of JAB Holding, told a German magazine, “We were speechless. We were ashamed….These crimes are disgusting.” Harf then promised, “As soon as [the historian’s] book is finished, we will publish it. Unadorned. The whole truth has to be on the table.” Without being prompted by lawsuits or pressured by advocacy groups, the family pledged 5 million euros in support of Holocaust survivors and 5 million euros to former forced laborers.

In 2020 the British pub chain and brewer Greene King emerged as another model for proactively acknowledging historical wrongs when it addressed the company founder Benjamin Greene’s enthusiastic support for the practice of slavery and his ownership of 231 human beings during the 1820s and 1830s. Greene King’s CEO, Nick Mackenzie, called this behavior “inexcusable” and told media outlets, “We don’t have all the answers, so that is why we are taking time to listen and learn from all the voices, including our team members and charity partners as we strengthen our diversity and inclusion work.”

What should an apology consist of? Martha Minow, a former dean of Harvard Law School, argues that good apologies “acknowledge the fact of harms, accept some degree of responsibility, avow sincere regret, and promise not to repeat the offense.” Ernesto Verdeja, an expert on apologies for mass crime, reminds those crafting responses to avoid making excuses for past actions.

Matthew Shain

The communications professor Claudia Janssen issues some additional advice based on her analysis of Aetna’s response to the slavery-related lawsuits: Companies should avoid using apologies to disassociate themselves from the prior regime or to bring closure. In 2002 an Aetna spokesperson said, “These issues in no way reflect Aetna today” and then went on to talk about the company’s current commitment to diversity and equity. The issue, however, is the past. What’s more, the company made several defensive statements along with the apology: It said it had “no way of knowing if the company profited” from the few recorded policies issued on enslaved people, and Aetna’s leaders refused to open its archives to independent historians to find out. The company’s stance did not build trust.

Finally, when responding to accusations, do not bring up acts of heroism or claims of victimization, as executives of the SNCF did repeatedly. When asked about the role their company played in the Holocaust, they often reminded their questioners of the heroism of SNCF railway workers on D-Day and the company’s material losses during the German occupation. Those statements, perhaps issued with the intention of both honoring heroes and satisfying the train union, were poorly received. Bringing up good deeds in the face of legitimate claims is a defensive move rather than a receptive one.

Respond Meaningfully

In 2011, nearly two decades after the first Holocaust-related lawsuit against the SNCF, Guillaume Pepy delivered yet another apology on its behalf to an audience of Holocaust survivors: “I want to express the SNCF’s deep sorrow and regret….In its name, I am humbled before the victims, the survivors, and the children of the deportees, and before the suffering, which lives on.” It was a moving statement, but not everyone was impressed. The plaintiffs’ attorney Harriet Tamen said, “Don’t bow down, write a check.” Lou Helwaser, whose mother had been deported, told me, “It sounded more like making excuses than taking real responsibility.”

Words without action are meaningless. Most executives are familiar with this basic tenet of service recovery, and it holds even for a major corporate atonement. Many are unsure how to respond to historical harm; they know it can’t be handled using the playbook of a routine service failure. So then how? The scale of damage caused by historical crimes can seem overwhelming. Research has shown that the legacies of the Holocaust, slavery, genocide, and colonialism affect the descendants in myriad ways through transgenerational trauma. Some estimates for appropriate slavery reparations in the United States total about $14 trillion. Should companies pay some reparations? If so, how much?

The answer is that at some point corporations facing up to historical crimes will need to write a check. How much and whom to pay should be decided not by the company alone, behind closed doors, but with the input of affected communities—ideally before litigation. The SNCF waited too long, but it was still able to turn opponents into allies through ongoing engagement. Serge Klarsfeld, a leading French activist, chastised the SNCF early on for its participation in the Holocaust, but eventually he guided many of its atonement-related activities. He urged the company’s leadership to install plaques at important sites and encouraged the SNCF to contribute to other Holocaust-related programs. Today it cosponsors many commemoration activities in France, including the annual Reading of the Names. Klarsfeld also directed the company to contribute to his orphans fund, which provided material support and recognition to some survivors. The French Jewish leadership largely accepted the SNCF’s acts of contrition. Klarsfeld even began serving as a lawyer for the company when it faced lawsuits in the United States.

For crimes without living survivors, companies can locate and support descendant communities. Georgetown University modeled one way to do that. Facing insolvency in 1838, Georgetown had sold 272 enslaved people to pay off its debts. In 2016 the university considered what support it could offer their descendants, the majority of whom were found to be living in a single town in Louisiana. It funded research to locate them and then offered them preferential admission and scholarships to study at the university. It also launched the Georgetown Slavery Archive, which provides a wealth of material on the institution’s slavery-related activities and information about those who were enslaved.Sign up for Leadership Must-reads from our most recent articles on leadership and managing people, delivered once a month. Sign Up

Georgetown students, through sit-ins and other forms of mobilization, advocated for even more action. In 2019 they voted to add $27 each to their student fees to support the Louisiana community. The institution now works with the community to identify useful investments. The students’ active participation demonstrates to companies that involving employees and shareholders builds internal support for contributions as it helps shape an organization’s ethos. Of course, not everyone will support engagement. More than a few vocal French Railways union members vehemently opposed any statement or activity that tarnished the SNCF’s image as a wartime hero. Executives must, as always, accept that their decisions will not please everyone.

Companies can also band together to coordinate their responses when evidence is found of industrywide participation in historical crimes. We saw the beginnings of such cooperation in 2000, when 6,500 Nazi-complicit German companies contributed to a foundation for survivors called Remembrance, Responsibility and Future. Unfortunately, rather than reflecting a true commitment to reparations, the foundation sought to put an end to what then German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder called a “campaign” against his country and German industry by the United States and Western Europe. Few of the companies that contributed to the foundation did more than contribute monetarily to the fund. Only a handful engaged in historical research; fewer still made public statements. That turned past participation in genocide and torture into just another cost of doing business. Still, the idea of joining forces has merit—especially if scale allows for more-meaningful contributions and responses to victim groups.

Finally, companies should avoid giving the impression that their contributions are a vanity project. While it’s fine for them to come up with their own ideas for commemoration, supporting existing projects and low-profile attendance at commemorative events demonstrates respect for what victims and their descendants suffered and also acknowledges that they best understand what they need to recover. The key for executives is to participate in a broader conversation without trying to control the narrative or put the issue to bed.

. . .

Shakespeare wrote, “The evil that men do lives after them.” I see this clearly when talking with those who survived such atrocities. Take Daniel, who was deported on the last train from Paris to Auschwitz. He hangs his only picture of his murdered parents at the foot of his bed. He and his brother both survived the camp, but the experience was so horrifying that he recently said to me, “I still wonder if it would have been better to die at Auschwitz.”

Historical atrocities like slavery and the Holocaust can never be fully repaired. But companies complicit in such events should not avoid their own reckoning. By their nature, executives feel most comfortable when focusing on the future. But the past has a habit of catching up with anyone who ignores or tries to outpace it. Corporate leaders may feel it’s not fair that they should have to devote their attention to making amends for their predecessors’ sins. But particularly in an era when society is scrutinizing and reassessing the history of both individuals and organizations, leaders must be ready to engage with—and atone for—their company’s past actions.

Corporations must first accept that it is their duty to respond to historical crimes. They should be totally transparent, apologize, and take cues from the field of transitional justice by working with victim communities and their descendants to make amends.A version of this article appeared in the January–February 2022 issue of Harvard Business Review.