LOS ANGELES — The ancestors of a Black family forced out of business nearly 100 years ago by officials of a wealthy coastal city south of Los Angeles are on the verge of recouping what once belonged to them.

On Tuesday, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously to begin the process of transferring beachfront property to the descendants of Charles and Willa Bruce, whose once-thriving resort in affluent Manhattan Beach was taken under eminent domain in 1924. A statewide bill was also introduced earlier this month that will allow Los Angeles County to return the land to the Bruce family’s descendants.

Returning Bruce’s Beach to the family that first developed the land is part of California’s broader push toward reckoning with its checkered past, which also includes reforming the criminal justice system and creating a pathway for reparation payments to descendants of slaves.

“People are looking at different kinds of ways to not just to rectify the racial injustice that happened last year [when George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police], but the racial injustice that’s been going on in the United States for years,” historian Alison Rose Jefferson said. “We’re at a time where we have more people in power who are willing to think about this as an option.”

In addition to a statewide bill that would remove legal barriers to returning the beachfront property to the Bruce family, California lawmakers are also weighing multiple proposals aimed at recalibrating the criminal justice system. This includes creating a pathway to decertify police officers who commit serious misconduct or violate a person’s civil rights. The amended bill, which was first introduced in 2019 by state Sen. Steven Bradford, a Democrat from Gardena, is named after a 25-year-old Black man who was shot and killed by police in 2018.

Bradford is also behind other reform efforts, including the creation of a cannabis equity program that would funnel millions in grant money to communities disproportionately affected by the so-called war on drugs. Bradford was appointed in February to a task force that will study and develop reparation proposals for Black Californians descended from slaves. In a statement issued at the time of his appointment to the task force, he said this is not just about slavery, but about “paying back a debt to those who have been mistreated for so long.”

“Never has the trauma of four million enslaved people and their descendants and the impact it continues to have been meaningfully acknowledged or addressed by our nation,” he said. “The consequences of these actions are felt today in many forms, not the least of which are the major disparities in life outcomes such as economic opportunity and quality of health care.”

Last year, California officials weighed a bill that would have encouraged public spaces, including parks, libraries and museums, to add statements acknowledging the institutions were “founded upon exclusions and erasures of many Indigenous peoples.” The bill passed in the state Assembly but later died in the Senate.

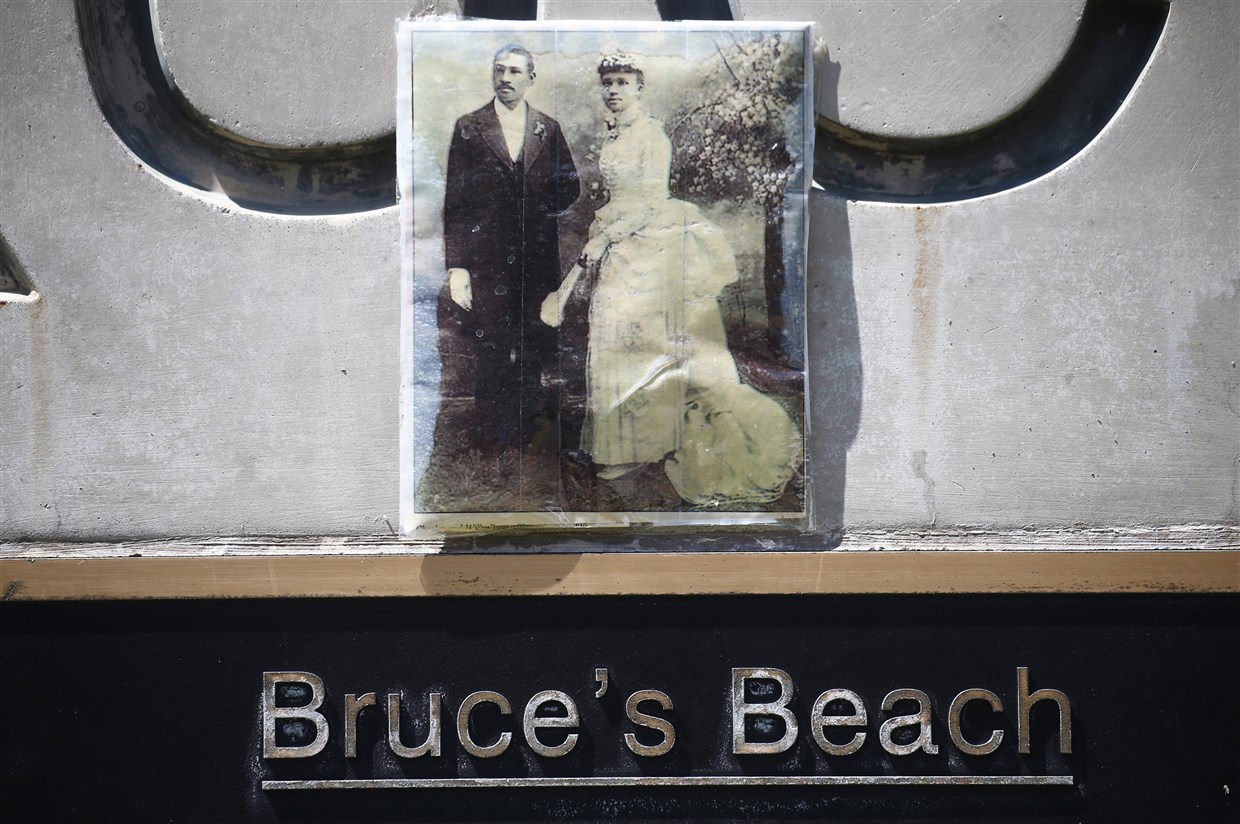

In Southern California, Bruce’s Beach, now commemorated by a plaque in the middle of a lush green park near the original beachfront property, has long stood as a reminder of Manhattan Beach’s dubious history. Wedged between residential streets, the park offers impressive views of the Pacific Ocean and one of the few green spaces in an otherwise heavily developed beach haven for wealthy residents, less than 1 percent of whom are Black, according to census data.

The parcel of land once owned by the Bruces was transferred to the state and then to Los Angeles County in 1995. It currently houses the Lifeguard Training Center.

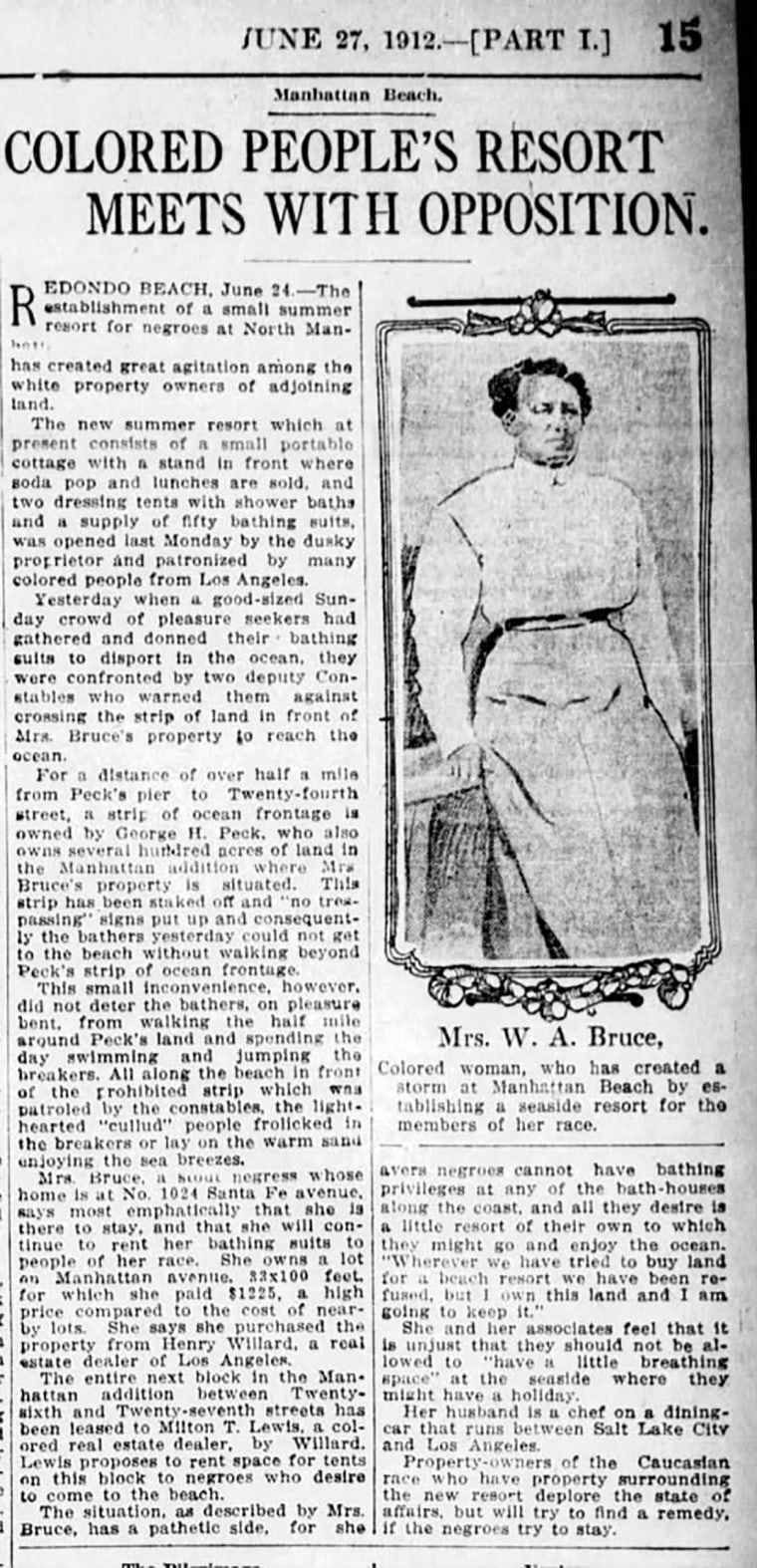

Charles and Willa Bruce first purchased their land in 1912 just as Manhattan Beach was becoming a popular destination for people from all over Southern California. Trolleys and trains carried passengers from as far as Pasadena, some 30 miles away near the San Gabriel Mountains. Their vision had been to build a coastal oasis where Black families could swim and mingle without being targeted or harassed.

“They were pioneers,” Jefferson said. “It was successful from day one and the African Americans there were harassed from day one.”

The resort included everything typical of a beach getaway – a changing room, dining room, residences and even a dancing hall. Willa Bruce ran the popular cafe and entertainment offerings while her husband worked as a chef on a train dining car. They purchased the land for $1,225.

Despite being located on a remote part of the coast, the Bruces were targeted by the Ku Klux Klan and other racist locals. City ordinances were passed to make it more difficult for outsiders to visit the beach, including making it illegal to change clothes in a car or park for more than one hour, Jefferson said. The KKK slashed tires and even left a burning mattress outside a property belonging to the Bruce family. Similar harassment was experienced in other parts of the county, including a Santa Monica beach pejoratively dubbed Inkwell, according to Jefferson.

In 1924, Manhattan Beach city officials seized the Bruces’ land under eminent domain, which was also invoked to take property from Japanese people across the state and Latino families who lived in the area near what is now home to Dodger Stadium.

The Bruce tried to fight the city and ultimately lost, winning just $14,500 for their beachfront land.

“I learned to swim just a couple of blocks from Bruce’s Beach,” said Los Angeles County Supervisor Janice Hahn. “I’m embarrassed that I didn’t know the story and how much pain it caused the Bruce family and how much pain it has caused other African Americans who did know the story and felt like there wasn’t going to be any righting of this wrong.”

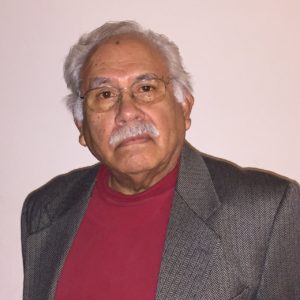

After their land was taken, the Bruce family moved to the city of Los Angeles and eventually out of the state. Their descendants are now scattered throughout the country, some living at or below the poverty line despite once owning land that is now thought to be worth several millions of dollars, said Chief Duane Yellow Feather Shepard, family spokesman and a distant relative of Charles and Willa Bruce.

Shepard, chief of the Pocasset Wampanoag Tribe of the Pokanoket Nation, is now working with other family members to track down descendants of relatives enslaved on various plantations throughout the country. Through these efforts, the family has reunited long lost connections but also been forced to face the lasting trauma of slavery in the United States.

“It’s traumatic to families to not know their history,” he said. “Returning Bruce’s Beach would certainly repair the damage done to Charles and Willa’s family who lost out on generational wealth, but it can never repair the trauma inflicted by the KKK.”

Manhattan Beach city officials said they will not offer a formal apology to the family despite repeated pleas from Hahn, county leaders and many residents. Instead, City Council members adopted a resolution earlier this month acknowledging and condemning the city’s past action and agreeing to install new historical markers at the site.

The city’s refusal to apologize underscores the tension between reckoning with injustice and finding a path forward, according to Vilma Ortiz, sociology professor at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“Apologies are a really important first step. They show acknowledgment that things happened that were wrong and it suggests people are going to change,” she said. “Apologies are good but they’re not enough.”