In the fight for Black liberation, African-American photographer, filmmaker, author and composer Gordon Parks (1912-2006) transformed storytelling into activism. “Finally, after a long search to find weapons to fight off the oppression of my adolescence, I found two powerful ones, the camera and the pen,” Parks wrote in 1997’s Half Past Autumn: A Retrospective. He avowed, “Racism is still around, but I am not about to let it destroy me.”

This was a lesson in survival gleaned in his youth. Born on Fort Scott, Kans., Parks weathered a childhood marked by abject poverty during one of the most violent eras of homegrown terrorism: Between 1877 and 1950, more than 4,440 lynchings occurred in the United States. At 11, Parks nearly met the same fate when three white boys threw him into the Marmaton River knowing he could not swim.

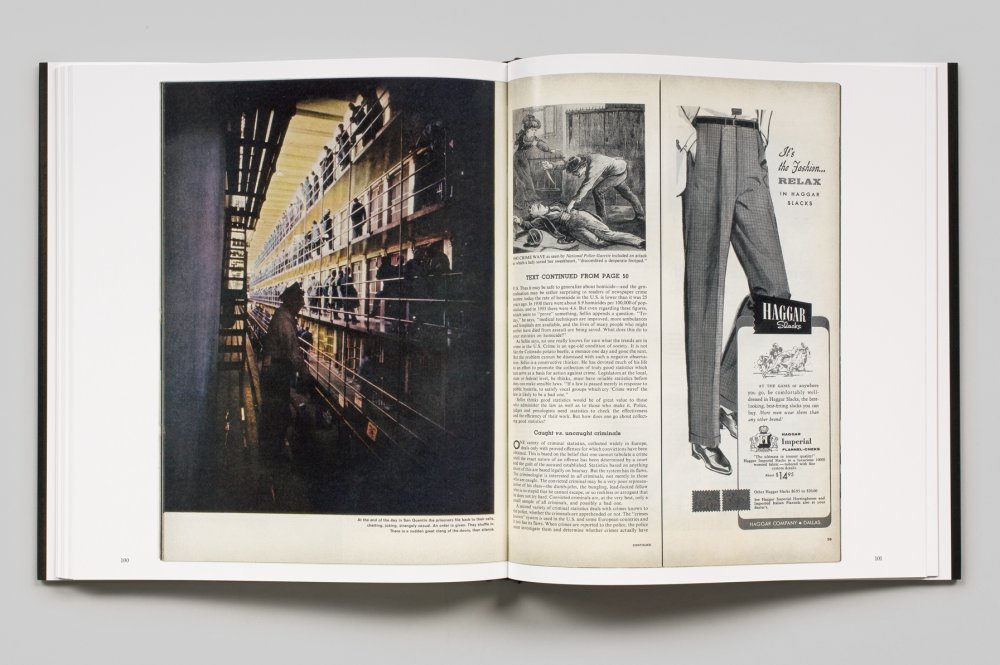

Parks rarely shared his harrowing history with those closest to him; instead he channeled his experiences into his art—including work that examined the role of the criminal-justice system in Black American life. Interior of Gordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime showing the original layouts as it appeared in LIFE magazine. © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation/Steidl

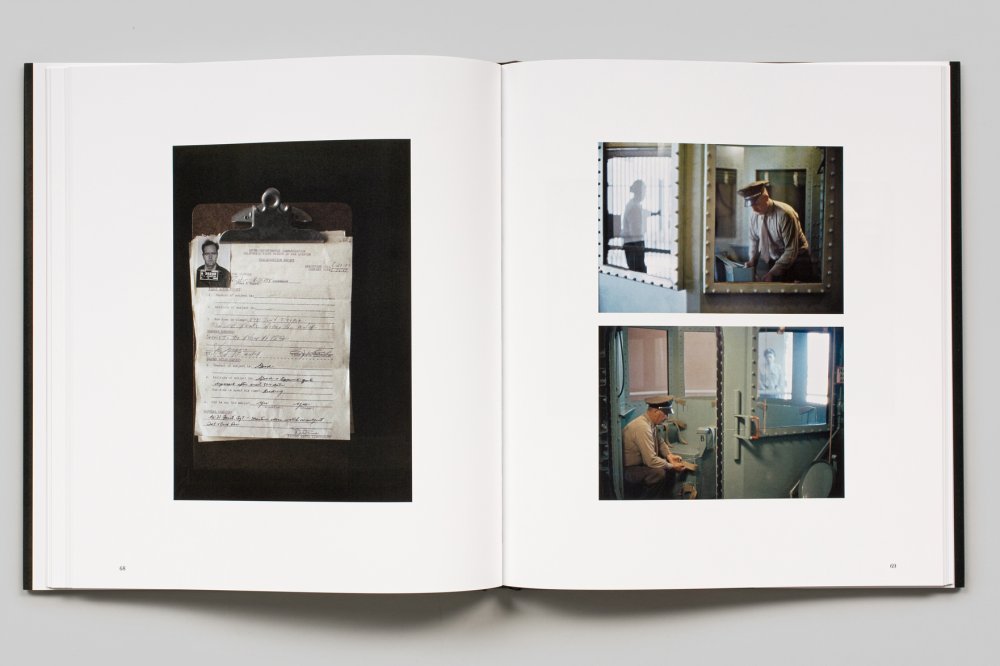

Interior of Gordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime showing the original layouts as it appeared in LIFE magazine. © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation/Steidl Interior view of Gordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime. © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation/Steidl

Interior view of Gordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime. © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation/Steidl

“Uncle Gordon wrote about his childhood in The Learning Tree, which became the movie that made him the first Black director in Hollywood,” says Robin Hickman-Winfield, Parks’ great-niece and founder of the Gordon Parks Legacy Educational Experience at Gordon Parks High School in St. Paul, Minn. “While he wasn’t on the picket lines, he shared it in his work so we would know our story. Black lives mattered to him.”

After his mother died, Parks, then 14, moved to St. Paul to live with his sister—but ended up on the streets where he learned to fend for himself. At 25, Parks discovered photography, getting his start at local Black-owned newspapers and the Farm Security Administration before becoming the first Black photographer to shoot for Vogue. In 1948, Parks pitched a story on Leonard “Red” Jackson, the teen leader of a Harlem gang, to LIFE magazine, creating a tender portrait of race, poverty and crime that won him a staff job.

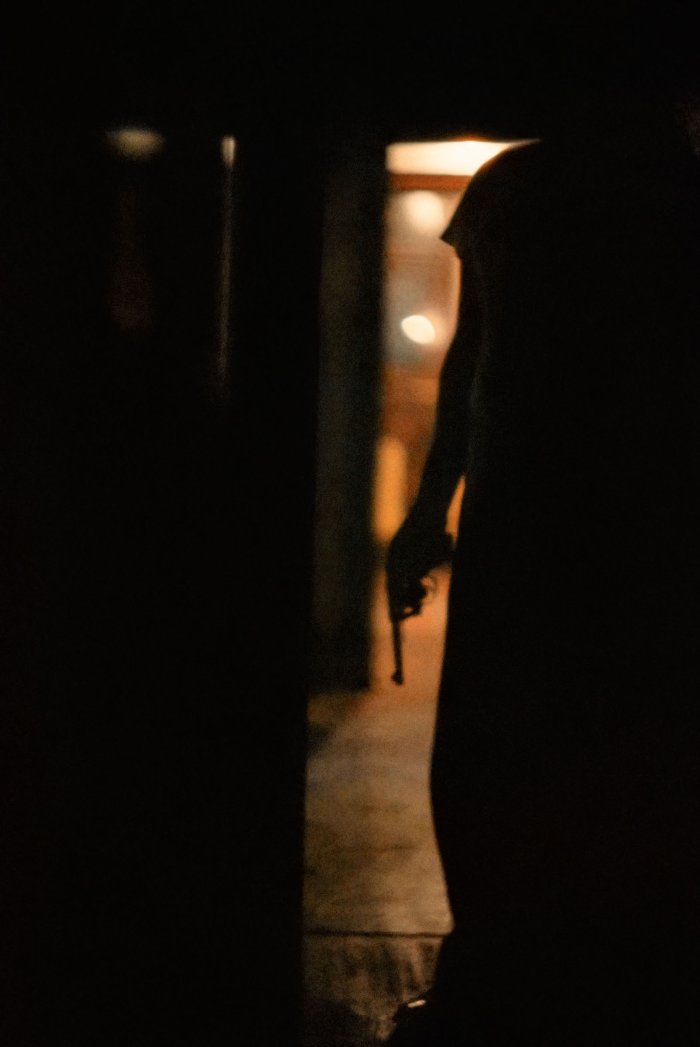

By the 1950s, as white America embraced rock ‘n’ roll and the “rebel without a cause” attitude of disaffected youth, the mainstream media seized upon many white readers’ fears of a coming wave of crime. LIFE magazine was on the case, announcing a major six-part series on crime in the U.S., which would explore the police, criminals, courts, punishments, prisons and parole, along with a psychological profile of crime itself. Untitled, Chicago, Illinois, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation Untitled, New York, New York, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Untitled, New York, New York, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

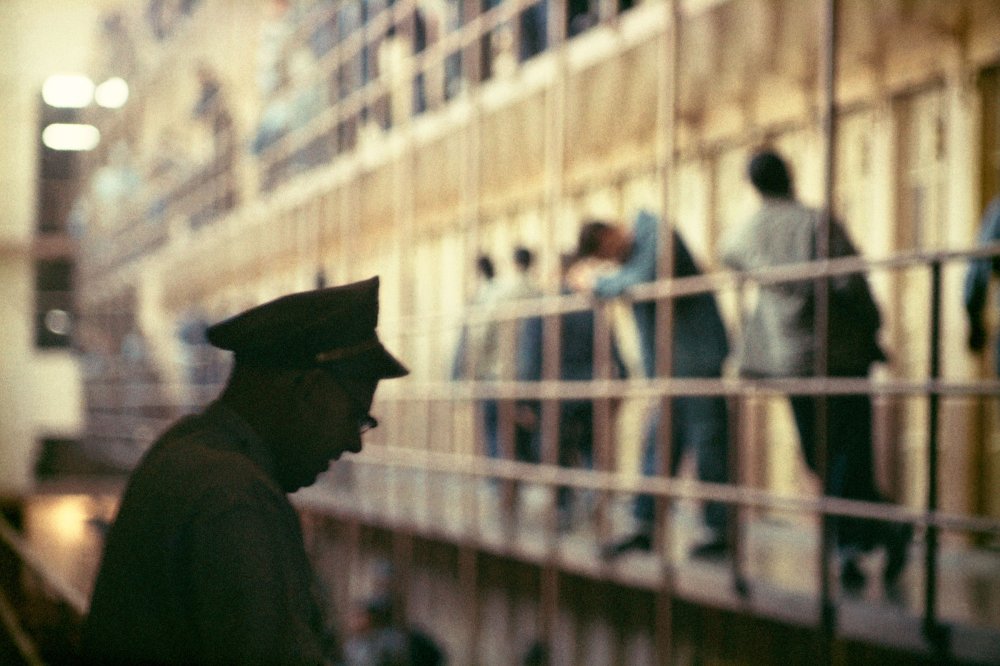

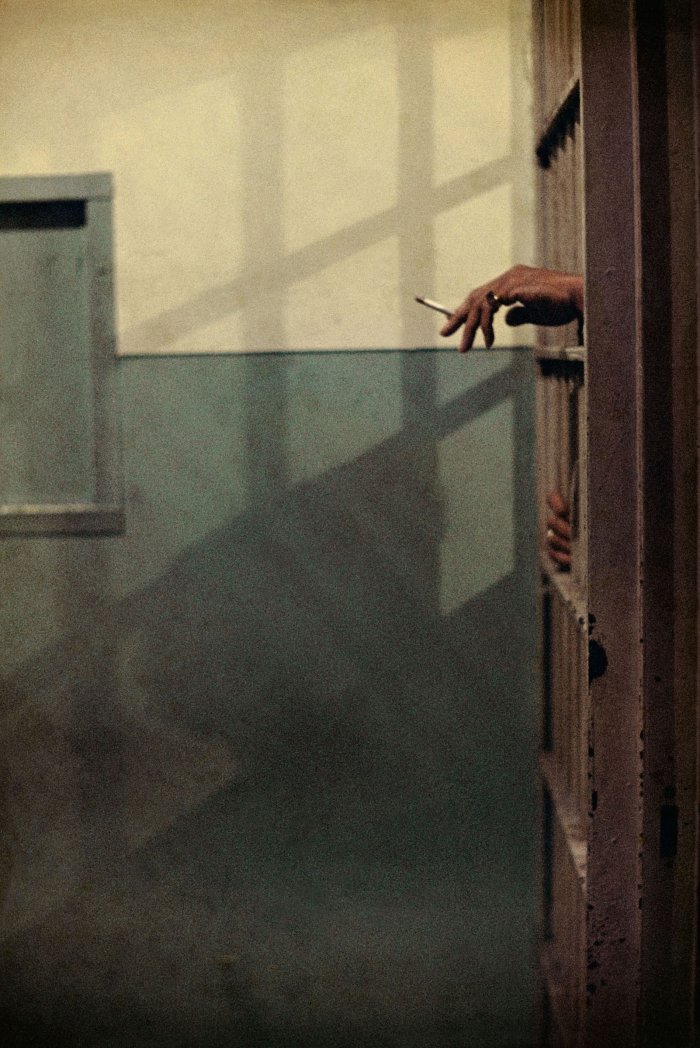

For the first installment, in the Sept. 9, 1957 issue of LIFE, Gordon Parks and reporter Henry Suydam collaborated on “The Atmosphere of Crime,” an eight-page photo essay documenting the police and prison systems in New York City, Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles. The new book, Gordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime, 1957 (STEIDL/The Gordon Parks Foundation in collaboration with MoMA), provides an in-depth study of this historic body of work.

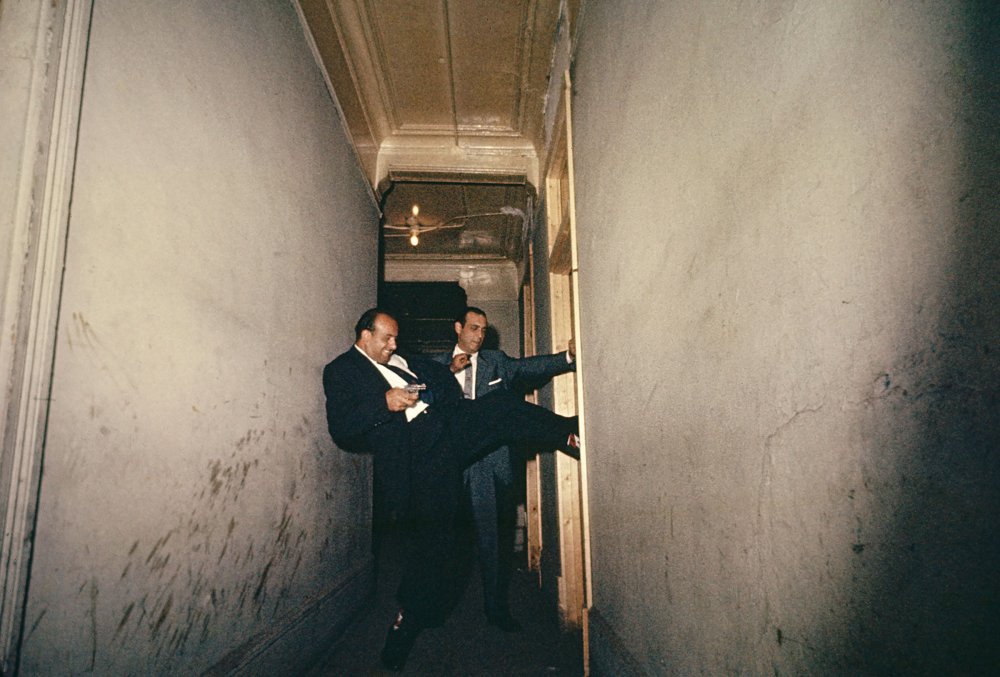

Robert Wallace, a senior staff writer who had previously written about Parks’ 1956 story on segregation in the South, wrote the text that accompanied the “Atmosphere of Crime” story, setting an foreboding tone in the opening sentences: “The nation in the fall of 1957 appears to be threatened by a catastrophic wave of crime. From almost every major city in the past year have come frightening reports showing not merely an increase in the number of crimes but a dreadful shift, it seems, in their nature.” Raiding Detectives, Chicago, Illinois, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Raiding Detectives, Chicago, Illinois, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation Untitled, Chicago, Illinois, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation Crime Suspect with Gun, Chicago, Illinois, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

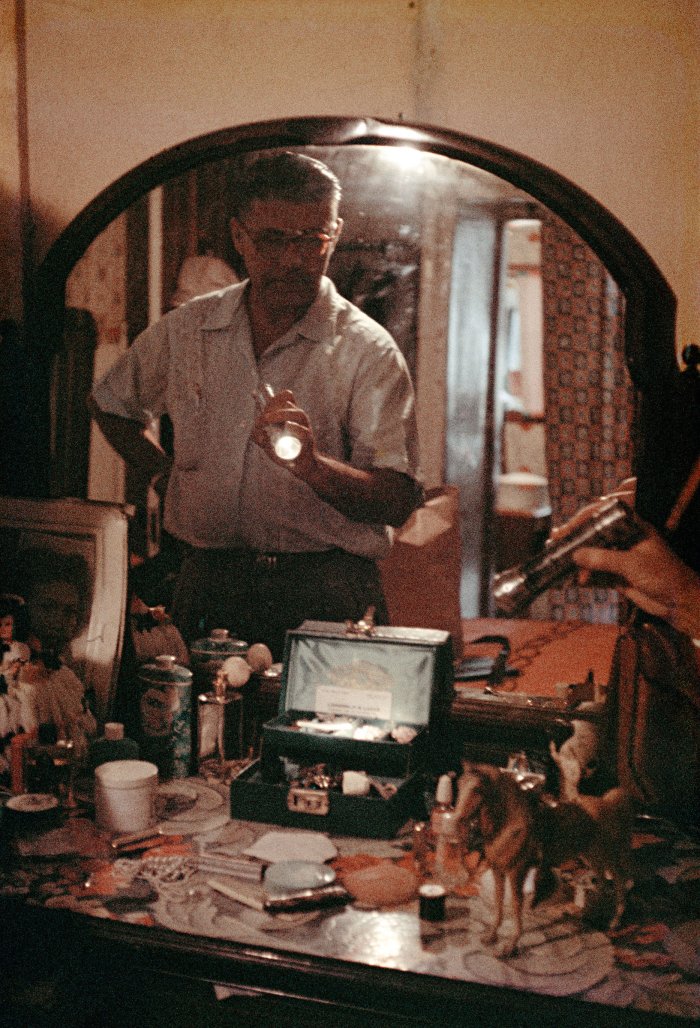

Crime Suspect with Gun, Chicago, Illinois, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation Drug search, Chicago, Illinois, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Drug search, Chicago, Illinois, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Adopting the framework of politicians, law-enforcement officials and criminologists, Wallace’s perspective was bleak, steeped in a vocabulary of menace and threat, citing reports that claimed “Negroes” and “juvenile delinquents” were responsible for the majority of crimes committed—but never investigating the system itself. While Wallace argued that the higher percentage of Black crime was a result of racism, he failed to explore the role of criminal justice in these systems of power.

Parks’ photographs told a different story, one that examined the underlying suffering, despair and fear of marginalized groups further exacerbated by police and prisons.

Parks trained his lens on law enforcement, documenting officers on patrol, interrogating suspects, kicking down doors, knocking people down and searching for needle marks on addicts’ arms. Though the suspects Parks photographed came from different racial backgrounds, one constant remains: the law enforcement agents were predominantly white. Untitled, San Quentin, California, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Untitled, San Quentin, California, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation Fingerprinting Addicts for Forging Prescriptions, Chicago, Illinois, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Fingerprinting Addicts for Forging Prescriptions, Chicago, Illinois, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Forgoing the dazzling aesthetics of film noir, which he had often turned to for other stories, Parks shot this series in color, in somber muted tones that prefigure the gritty mood of 1970s films like his blockbuster Shaft. In place of sharp crisp edges and sharply defined black and white, everything in Parks’ photos is met with blur and haze, suggesting an air of ambiguity and doubt. In 1990’s Voices in the Mirror: An Autobiography, Parks wrote, “With the publication of that essay came invitations to speak before groups concerned with the problems of crime and ways to fight them. Against a mature judgment I accepted a few. But I had no reassuring answers; I too was begging the questions, eating the same despair.”

Parks found other ways to reckon with the issues he confronted in his work. In the 1970s, he accompanied his nephew, Robert “Bobby” Hickman, to Minnesota’s Stillwater Correctional Facility to visit inmates. “Uncle Gordon served as a vision of possibilities and hope. He wanted those brothers to see him as a vision of possibility, telling them, ‘You brothers can write, write about your experience,’” says Parks’ great-niece Hickman-Winfield, who launched the CHOICE of Weapons Fellowship at the Redwing Juvenile State Correctional Facility in 2004. “I remember seeing Uncle Gordon standing in his kitchen, crying as he read a letter from a young Black man who was not wasting his time while doing time,” she says of one their final visits before his death in 2006.

Hickman-Winfield fights back tears as she speaks, just hours after Gordon Parks High School hosted its graduation ceremony in the parking lot due to COVID-19 on June 5. Although they weren’t able to have their prom, students were able to celebrate earlier this year at the opening of Choice of Weapons: Honor and Dignity, The Visions of Gordon Parks and Jamel Shabazz, curated by Hickman-Winfield at the Minnesota Museum of American Art. “We’re in a Black moment right now,” she says. “I can hear Uncle Gordon say ‘Let’s do it, baby!’” Untitled, Illinois, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Untitled, Illinois, 1957 © Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Correction, July 29

The original version of this story misstated the name of the museum where A Choice of Weapons: Honor and Dignity was held. It was the Minnesota Museum of American Art, not the Minneapolis Museum of American Art.