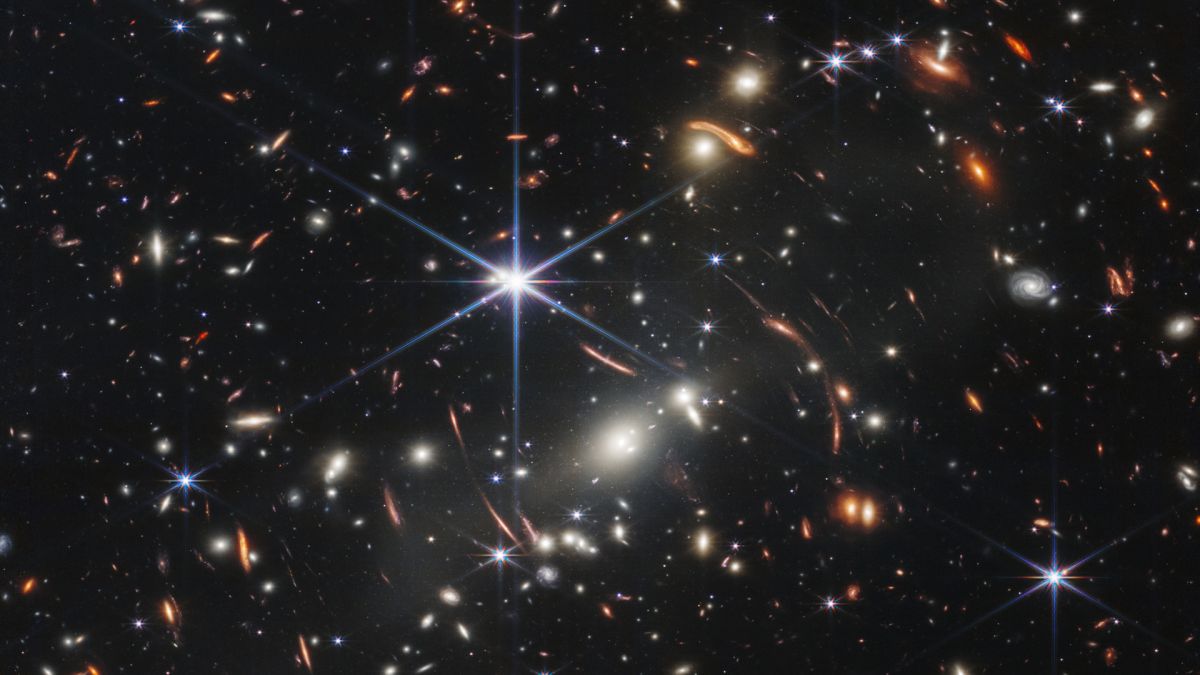

From tracking the seasons to “following the gourd” to freedom, knowledge of the stars was imperative for enslaved Africans. Their descendants are reclaiming those ties.

Historically, Black Americans had very good reasons to be afraid of the dark. In a segregated South under Jim Crow laws, “sundown towns” imposed curfews on Black people, threatening—and delivering—violence if they remained outside after sunset.

But Black people have also found consolation in the night sky. “One of the most heartbreaking things about slavery in the U.S. was people being forced apart,” says astronomer Moiya McTier. “I imagine there might have been some small comfort in knowing that wherever they were, they were seeing the same stars.”

McTier is a rarity in astronomy circles—a Black woman in a field estimated to be 90 percent white. In fact, a 2020 Forbes article reported that only about 2 percent of astronomers are Black.

Astronomers including McTier are hoping that will change as stargazing becomes more popular due to the pandemic and destinations promote ways for people of all ages to learn about the heavens.

HISTORIC CONNECTIONS

For ancestors of America’s enslaved people, the night sky was especially meaningful. An understanding of the stars and planets was one of the few things that West Africans stolen from the continent were able to bring across the Atlantic.

The constellations held important cultural stories and lessons that were passed down through the generations. That oral storytelling tradition became an important tool for Harriet Tubman, Josiah Henson, and others, who used “signal songs,” such as “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” to convey detailed instructions for taking the Underground Railroad to freedom. The “drinking gourd” was a code name for the Big Dipper constellation, which was used to locate Polaris (the North Star).

(Secrets of Harriet Tubman’s life are being revealed 100 years later.)

The ability to read the skies was imperative to the survival of enslaved and free Africans who farmed so much of America, helping them track time, weather, and seasons. “They had to know a lot of observational astronomy to know when to plant the crops because it’s not like they were being taught these things that they were being forced to do,” says McTier, who studied astronomy and folklore at Harvard University.

That knowledge didn’t start with slavery or end with Jim Crow. The constellations we recognize today may have been largely attributed to the Greeks, but the Greeks themselves borrowed from Egyptian and Babylonian mythology, says McTier.

(A new tool hopes to uncover the lost ancestry of African Americans.)

A BRIGHT FUTURE

Despite this history, there have been few prominent Black astronomers. Many people today may know Neil DeGrasse Tyson, but few have heard of Benjamin Banneker. He was a free Black man born in the 1700s who taught himself astronomy and wrote one of the first accurate almanacs in modern history. He also predicted a solar eclipse and did some of the survey work that led to the planning of Washington, D.C.

Encouraging more African American youth and amateur stargazers to follow in Banneker’s and Tyson’s footsteps has become a focus for Ashley Walker, an atmospheric sciences graduate student at Howard University. During Black History Month in 2020, she started the hashtag #blackinastro as a way for like-minded folks to find each other. That effort has since grown to become Black in Astro, a networking organization—with nearly 6,000 followers on Twitter to date—that aims to inspire and assist Black students in astronomy.

(The unappreciated legacy of African American scientists and inventors.)

“Black astronomers, planetary scientists, astronauts in space, industry leaders, entrepreneurs, space lawyers, and on and on—we are here, and we are amazing.” says Walker.

Growing interest in astronomy as a hobby could help increase diversity in the field as well. It’s easier than ever for anyone to learn the difference between Ursa Major and Ursa Minor. Apps such as Skyview and Sky Safari and websites like U.K.-based Go Stargazing are portable pocket guides to the stars.

With 195 Dark Sky Preserves (DSP) around the world, travelers have their pick of clear views for glimpsing meteor showers and Saturn’s rings. Budding star watchers don’t have to rough it, either. In Phoenix, Arizona, Adero Hotel touts its location within a DSP, where you can stargaze from the balcony of your room. At the Four Seasons Scottsdale, a resident NASA astronomer offers weekly lectures (contact the hotel for the schedule). Volunteer science projects such as Zooniverse encourage sharing observations with scientists, which can impact new learning.

(Here are the best Dark Sky Preserves to stargaze in the United States.)

The hope is that these activities will stir curiosity and early interest in the field, especially for young African Americans who, compared to other groups, are disproportionately dropping out of STEM streams, which are key to pursuing an astronomy career.

“We need to stop the leak” of students dropping out, says McTier. “One way to do that is to make it very clear that Black people, African Americans, and ancient Africans before the slave trade contributed so much to astronomy.”

Heather Greenwood Davis is a freelance writer, on-air travel expert, and frequent contributor to National Geographic. Find her on Instagram and Twitter.