A new book documents the triumphs and challenges of more than 10,000 women who worked behind the scenes of wartime intelligence

It was a woman code breaker who, in 1945, became the first American to learn that World War II had officially ended.

The Army and Navy’s code breakers had avidly followed messages leading up to that fateful day. Nazi Germany had already surrendered to the Allies, and tantalizing hints from the Japanese suggested that this bloody chapter of history might soon come to an end. But when U.S. Army intelligence intercepted the Japanese transmission to the neutral Swiss agreeing to an unconditional surrender, the task fell to Virginia D. Aderholt to decipher and translate it.

Head of one of the Army’s language units, Aderholt was a master at the cipher the Japanese used to transmit the message—teams crowded around her as she worked. After the Swiss confirmed Japanese intent, the statement was hurried into the hands of President Harry S. Truman. And on the warm summer evening of August 14, 1945, he made a much-anticipated announcement: World War II was finally over.

Throngs of Americans took to the streets to celebrate, cheering, dancing, crying, tossing newspaper confetti into the air. Since that day, many of the men and women who helped hasten its arrival have been celebrated in books, movies and documentaries. But Aderholt is among a group that has largely gone unnoticed for their wartime achievements.

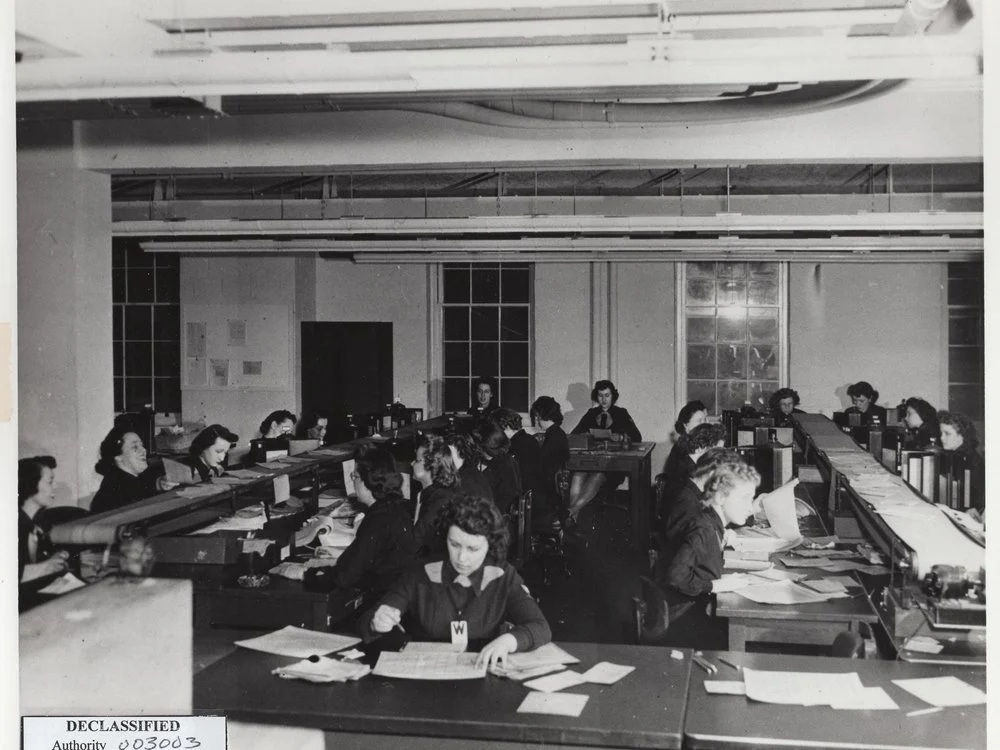

She is just one in upwards of 10,000 American women codebreakers who worked behind the scenes of WWII, keeping up with the conveyor belt of wartime communications and intercepts. These women continually broke the ever-changing and increasingly complex systems used by the Axis Powers to shroud their messages in secrecy, providing vital intelligence to the U.S. Army and Navy that allowed them to not only keep many American troops out of harm’s way but ensure the country emerged from war victorious.

The information they provided allowed the Allied forces to sink enemy supply ships, gun down the plane of Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of Pearl Harbor, and even help orchestrate the invasion of Normandy. During the later years of war, the intelligence community was supplying more information on the location of enemy ships than American servicemen could keep up with.

“The recruitment of these American women—and the fact that women were behind some of the most significant individual code-breaking triumphs of the war—was one of the best-kept secrets of the conflict,” writes Liza Mundy in her new book Code Girls, which finally gives due to the courageous women who worked in the wartime intelligence community.

Some of these women went on to hold high-ranking positions—several even outranking their military husbands. Yet to this day, many of their families and friends never knew the instrumental role they played in protecting American lives.

Mundy happened upon the story while her husband was reading Robert Louis Benson and Michael Warner’s book on the Venona project, a U.S. code-breaking unit focused on Russian intelligence during WWII and the Cold War. One particular detail of Venona surprised Mundy: the project was mostly women.

Curiosity piqued, she began digging into the topic, heading to the National Cryptologic Museum and the National Archives. “I didn’t realize at that point that the Russian codebreaking women were just a tiny part of a much larger story,” she says. “I thought I would spend a week in the archives. Instead, I spent months.”

Mundy, a New York Times bestselling author and journalist with bylines in The Atlantic, The Washington Post and elsewhere, dug through thousands of boxes of records, scouring countless rosters, memos and other paper ephemera. She filed declassification reviews, which turned up even more materials. “It turned out that there was a wonderful record out there, it just had to be pieced together,” she says.

Mundy even tracked down and interviewed 20 of the codebreakers themselves, but for some it required a bit of cajoling. During the war, it was continually drilled into them that “loose lips sink ships,” she says. And to this day, the women took their vows of secrecy seriously—never expecting to receive public credit for their achievements. Though many of the men’s tales have leaked out over the years, “the women kept mum and sat tight,” she says.

“I would have to say to them, ‘Look, here are all these books that have been written about it,'” Mundy recalls. “The NSA says it’s okay to talk; the NSA would like you to talk,” she would tell them. Eventually they opened up, and stories flooded out.

Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, which propelled America’s entrance into the war, Army and Navy intelligence employed a couple hundred people. The intelligence field was in its infancy. The CIA didn’t yet exist and the forerunner of what would later become the NSA had just been established. With war on the horizon, federal agencies were already working to recruit potential codebreakers and intelligence officers, but men were also needed for the armed forces, prepping for war. So as the agencies located suitable candidates, the men would be “gobbled up by the active militaries,” Mundy says.

Many men also weren’t interested in the job. At the time there was little prestige in the work; the battlefield was where heroes were born. Those who worked behind the scenes could say little about their accomplishments. And the work was seen as secretarial in some ways, Mundy notes.

It wasn’t until after Pearl Harbor that the real push to grow the ranks of intelligence began. In the weeks leading up to this fateful day, there was a sense of impending danger, but exactly where and when that assault would take place remained a mystery. Just days before the attack, the Japanese changed up part of their coding system. The codebreakers scrambled to crack the new intercepts—but it was too late.

Why the U.S. was caught by surprise would be hashed and rehashed over the years—from conspiracy theories to congressional hearings. But the loss emphasized the growing need for enemy intelligence. And with an increasing number of men being shipped out overseas, the government turned to an abundant resource that, due to sexist stereotypes of the day, were assumed to excel at such “boring” tasks as code breaking: women.

The Army and Navy plucked up potential recruits from across the country, many of whom were or planned to become school teachers—one of the few viable careers for educated women at the time. Sworn to secrecy, these women left their loved ones under the pretense of doing secretarial work.

Unlike the men, women code breakers initially signed onto the Army and Navy as civilians. It wasn’t until 1942 that they could officially join with many lingering inequities in pay, rank and benefits. Despite these injustices, they began arriving in Washington D.C. by the busload, and the city’s population seemed to swell overnight. Exactly how many of these women contributed to wartime intelligence remains unknown but there were at least 10,000 women codebreakers that served—and “surely more,” Mundy adds.

America wasn’t the only country tapping into its women during WWII. Thousands of British women worked at Bletchley Park, the famous home of England’s codebreaking unit. They served a number of roles, including operators of the complex code-breaking computers known as the Bombe machines, which deciphered the German Enigma intercepts. While the American codebreakers did assist the Allies in Europe, the majority of their work focused on the Pacific theater.

Just as women were hired to act as “computers” in astronomy to complete the rote, repetitive work, “the same was true with codebreaking,” says Mundy. And though it was repetitive, the job was far from easy. There were endless numbers of code and cipher systems—often layered to provide maximum confusion.

Codebreaking entails days of starting at strings of nonsensical combinations of letters, seeking patterns in the alphabetical chaos. “With codes, you have to be prepared to work for months—for years—and fail,” Mundy writes.

Over the years, the teams learned tricks to crack into the messages, like looking for the coded refrain “begin message here,” which sometimes marked the start of a scrambled message. The key was to discover these “points of entry,” which the code breakers could then tug at, unraveling the rest of the message like a sweater.

Many of the women excelled at the work, some showing greater persistence than the men on the teams. One particular triumph was that of junior cryptanalytic clerk Genevieve Grotjan, who was hired at age 27 by William Friedman—famed cryptanalyst who was married to the equally brilliant cryptanalyst pioneer Elizabeth Friedman.

Always a stellar student, Grotjan graduated summa cum laude from her hometown University of Buffalo in 1939. Upon graduation she hoped to go on to teach college math—but couldn’t find a university willing to hire a woman. Grotjan began working for the government calculating pensions but her scores from her math exams (required for pay raises) caught Friedman’s eye, Mundy writes.

Friedman’s team was working to break the Japanese diplomatic cryptography machine dubbed Purple. When Grotjan joined on, they had already been working on it for months, forming hypothesis after hypothesis to no avail. The British had already abandoned the seemingly impossible task.

The men on the team had years or even decades of experience with codebreaking, Mundy notes. But on the afternoon of September 20, 1940 it was Grotjan who had the flash of insight that led to the break of the Purple machine. “She’s a shining example of how important it was that Friedman was willing to hire women,” says Mundy. “Inspiration can come from many different quarters.”

The ability to read this diplomatic code allowed Allied forces to continually take the pulse of the war, giving them insight into conversations between governments collaborating with the Japanese throughout Europe.

But the work was not all smooth sailing. Shoved in crowded office buildings in the heat of the summer, the job was physically demanding. “Everybody was sweating, their dresses were plastered to their arms,” Mundy says. It was also emotionally draining. “They were very aware that if they made a mistake somebody might die.”

It wasn’t just intelligence on foreign ships and movements—the women were also decrypting coded communications from the American troops relaying the fate of particular vessels. “They had to live with this—with the true knowledge of what was going on in the war … and the specific knowledge of their brothers’ [fates],” says Mundy. Many cracked under the pressure—both women and men.

The women also had to constantly work against public fears of their independence. As the number of military women expanded, rumors spread that they were “prostitutes in uniform,” and were just there to “service the men,” Mundy says. Some of the women’s parents held similarly disdainful opinions about military women, not wanting their daughters to join.

Despite these indignities, the women had an influential hand in nearly every step along the path toward the Allies’ victory. In the final days of war, the intelligence community was supplying information on more Japanese supply ships than the military could sink.

It wasn’t a dramatic battle like Midway, but this prolonged severing of supply lines was actually what killed the most Japanese troops during the war. Some of the women regretted their role in the suffering they caused after the war’s end, Mundy writes. However, without the devoted coterie of American women school teachers reading and breaking codes day after day, the deadly battle may well have continued to drag on much longer.

Though the heroines of Code Girls were trailblazers in math, statistics and technology—fields that, to this day, are often unwelcoming to women—their careers were due, in part, to the assumption that the work was beneath the men. “It’s the exact same reductive stereotyping that you see in that Google memo,” says Mundy, of the note written by former Google engineer James Danmore, who argued that the underrepresentation of women in tech is the result of biology not discrimination. “You see this innate belief that men are the geniuses and women are the congenial people who do the boring work.”

Mundy hopes that her book can help chip away at this damaging narrative, demonstrating how vital diversity is for problem solving. Such diversity was common during the war: women and men tackled each puzzle together.

“The results are proof,” Mundy says.