The scanty suit’s explosive start is intimately tied to the Cold War and the nuclear arms race

Jennifer Le ZotteMay 21, 2015

:focal(541x86:542x87)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/99/ee/99ee0cb4-117d-4528-a0e3-6a5e2285a164/be064855web.jpg)

The cover of this year’s Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue, featuring a honey-haired model tugging at the bottom of her snake-print string bikini, generated swift reaction. The steamy glimpse of her pelvis prompted howls of outrage—risque, racy, inappropriate, pornographic, declared the magazine’s detractors. “It’s shocking, and it’s meant to be,” wrote novelist Jennifer Weiner in the New York Times.

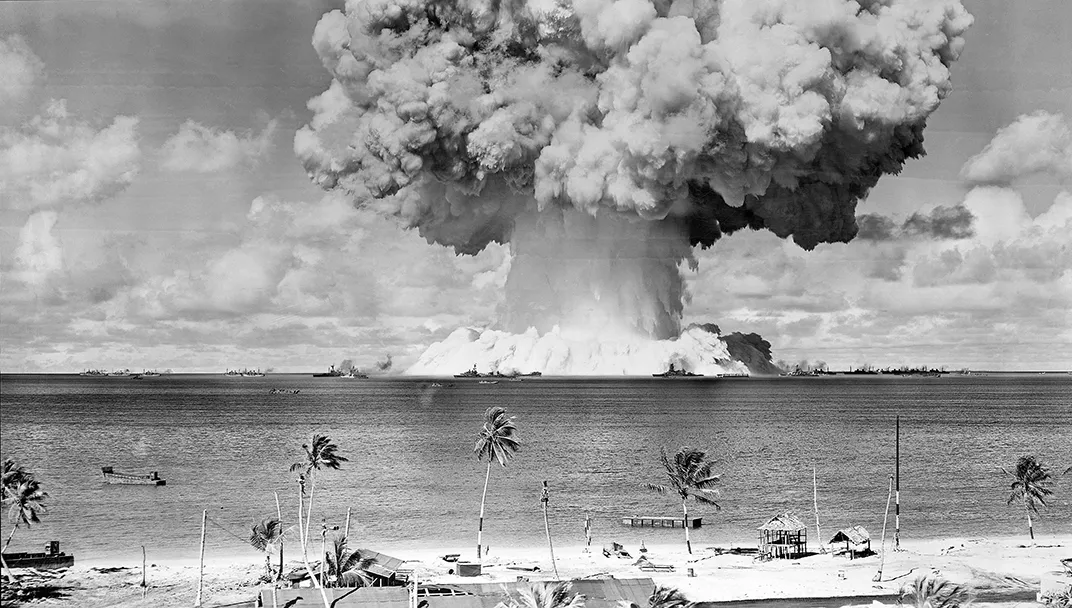

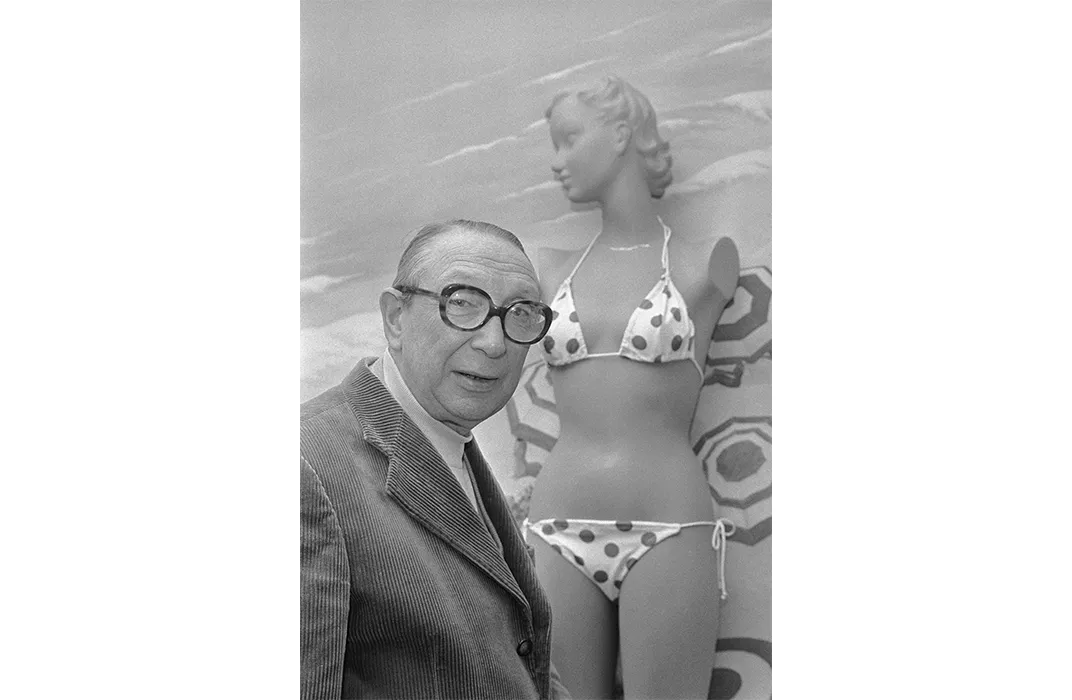

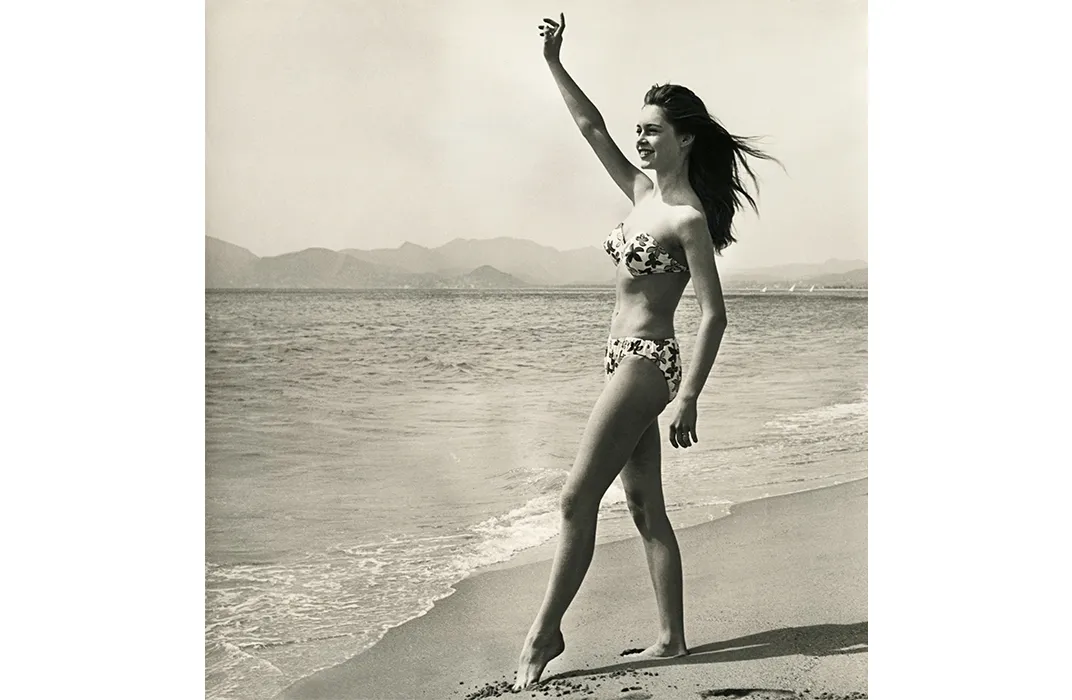

But when French automobile engineer-cum-swimsuit designer Louis Réardlaunched the first modern bikini in 1946, that seemingly skimpy suit was equally shocking. The Vatican formally decreed the design sinful, and several U.S. states banned its public use. Réard’s take on the two-piece—European sunbathers had worn more ample versions that covered all but a strip of torso since the 1930s—was so flesh-baring that swimsuit models were unwilling to wear it. Instead, he hired nude dancer Micheline Bernardini to debut his creation at a resort-side beauty pageant on July 5, 1946. There, Réard dubbed the “four triangles of nothing” a “Bikini,” named after the Pacific Island atoll that the United States targeted just four days earlier for the well-publicized “Operation Crossroads,” the nuclear experiments that left several coral islands uninhabitable and produced higher-than-predicted radiation levels.

How the Meaning of Thanksgiving Has Changed

Réard, who had taken over his mother’s lingerie business in 1940, was competing with fellow French designer Jacques Heim. Three weeks earlier, Heim had named a scaled-down (but still navel-shielding) two-piece ensemble the Atome, and hired a skywriter to declare it “the world’s smallest bathing suit.”

Réard’s innovation was to expose the bellybutton. Purportedly, Réard—who hired his own skywriter to advertise the new bikini as smaller than the world’s smallest bathing suit—claimed his version was sure to be as explosive as the U.S. military tests. A bathing suit qualified as a bikini, said Réard, only if it could be pulled through a wedding ring. He packaged the mere thirty squares inches of fabric inside a matchbox. Though Heim’s high-waisted version was embraced immediately and worn on international beaches, Réard’s bikini would be the one to endure.

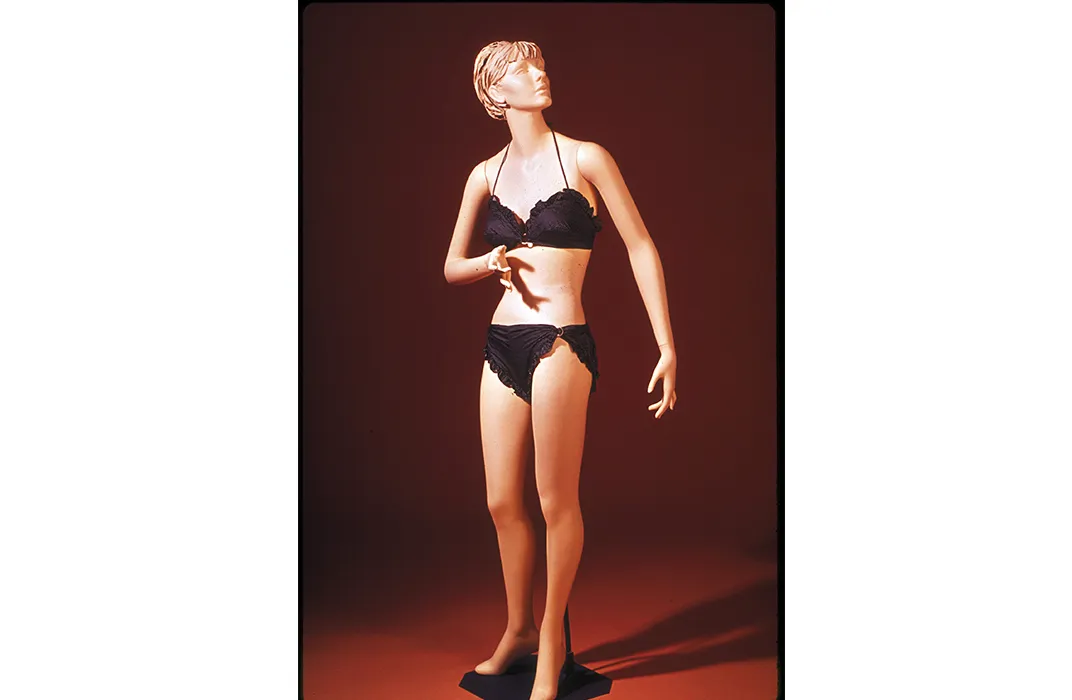

Beyond Europe, reception for Réard’s teenie, weenie bikini was as lukewarm as the San Tropez shores that inspired the all but bare-bottomed design. U.S. acceptance of the suit would require not only bikini-clad appearances on the silver screen by Brigitte Bardot, but also by Disney’s wholesome mouseketeer Annette Funicello. A later version of the bellybutton-baring bikini is held in the collections of Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. It was designed by Mabs of Hollywood and dates to the 1960s and is quite modest compared to Réard’s initial conception.

World War II rations on fabric set the stage for the bikini’s success. A U.S. Federal law enacted in 1943 required that the same synthetics used for bathing-suit production be reserved for the production of parachutes and other frontline necessities. So the thriftier two-piece suit was deemed patriotic–but of course, the design modestly hid the bellybutton, not unlike the halter-topped “retro” swimsuits famously favored today by pop superstar Taylor Swift. In the meantime, Mabs of Hollywood, the designer of the shiny black Smithsonian suit, gained its reputation making those modest two pieces during World War II, when American fashion mavens were limited to stateside designers.

The competition between swimsuit designers in 1946 laced with language related to the new weapons of mass destruction was not just a curious fluke. Historians of the Cold War Era such as the authors of Atomic Culture: How We Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb have noted that advertisers capitalized both on the public’s lurid fascination, as well as its fear, of nuclear annihilation.

One of the hot stories of the summer in 1946 was the naming of the first Operation Crossroads bomb after actress Rita Hayworth. All summer, international news reports buzzed with details of the Pacific Island nuclear tests designed to study the effects of atomic weapons on warships, and the homage to the leggy star was no exception.

Actor Orson Welles, who happened to be married to Hayworth at the time, broadcast a radio show on the eve of the first bomb’s release near the Bikini Atoll. He added a “footnote on Bikini. I don’t even know what this means or even if it has meaning, but I can’t resist mention of the fact that this much can be revealed concerning the appearance of tonight’s atom bomb: it will be decorated with a photograph of sizeable likeness of the young lady named Rita Hayworth.” An image of the star was stenciled onto the bomb below Gilda, her character’s name in the current film of the same name, whose trailer used the tagline: “Beautiful, Deadly. . .Using all a woman’s weapons.”

In that same radio show, Welles mentioned a new garishly red “Atom Lipstick” as an example of “the cosmetic being fashioned according to the popular conceptions of the original war-engine.” That very week, Réard would offer the bikini as yet another, more enduring example of the same.

Equating military conquest and romantic pursuits is nothing new—we’ve all heard that “all’s fair in love and war.” But this trope got considerably sexed up during the war between the Axis and the Allies. Pin-up girls pasted on the noses of WWII bombers (“nose art”) kept American soldiers company on long tours, and the sexy songstresses who entertained troops were dubbed “bombshells.” But an even weirder tone to the innuendoes crept into the lingo once nuclear weaponry appeared. Women’s bodies, more readily on display than ever before, became dangerous and tempting in magazine advertizements, even weaponized in competitions like the 1957 Miss Atomic Bomb champion. The scandalously scant bikini was simply an early example of this postwar phenomenon.

Allusions to nuclear destruction multiplied after Russia developed its A-bomb in 1949 and the Cold War escalated. In the battle between capitalism and communism, economic growth took top billing. Tensions between the U.S. and Russia included debates over which system provided the best “stuff” for their citizens—like the famous 1959 “Kitchen Debates” between then vice-president Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev over which country’s “housewives” had better home conveniences. Technological resources and consumer satisfaction became a popular measure of Cold War American success.

As Cold War anxieties grew, Americans bought more consumer goods and a greater variety of them than ever before. Mad Men-style advertisers and product designers eager to capture valuable consumer attention played to the public’s fixation with nuclear disaster—and its growing interest in sex. Hit songs like “Atomic Baby” (1950) and “Radioactive Mama” (1960), paired physical allure and plutonium effects, while Bill Haley and the Comets’ 1954 hit “Thirteen Women”turned the fear of nuclear catastrophe into a fantasy of masculine control and privilege. All in all, a startling number of the songs in Conelrad’s collection of Cold War music link love, sex and atomic disaster.

We all know sex sells. In 1953—the same year Senator Joseph McCarthy’s widely publicized communist witchhunt peaked and the Korean War suffered its dissatisfying denouement—Hugh Hefner upped the ante with his first, Marilyn Monroe-festooned issue of Playboy. The 1950s Playboy magazines did not just sell male heterosexual fantasies; they also promoted the ideal male consumer, exemplified by the martini-drinking, city-loft-living gentlemen rabbit featured on the June 1954 cover. The bikini, like lipstick, girly mags, blackbuster films and pop music, was something to buy, one of many products available in capitalist countries.

Clearly, plenty of American women chose to expose their tummies without feeling like dupes of Cold War politics. Women’s own preferences had a firm hand in shaping most 20th-century fashion trends—female sunbathers at St. Tropez reportedly inspired Réard’s trim two piece because they rolled down their high-waisted suits to tan. But if the 2015 Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue controversy is any indication, the bikini is still all about getting an explosive reaction. The barely-there beachwear’s combative reputation, it seems, has a half-life not unlike plutonium. So maybe, given the bikini’s atomic origins and the continuing shock-waves of its initial detonation, pacifism (along with Brazilian waxes and punishing ab routines) gives women another reason to cover up this summer—a one-piece for peace?

Homeward Bound

Atomic Culture: How We Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Atomic History & Culture)

Get the latest on what’s happening At the Smithsonian in your inbox.