The Eisenberg Institute for Historical Studies conducted an online event Friday afternoon to discuss the possibility of “radical futures” through an analysis of Indigenous political thought.

Featuring four panelists, the symposium explored the contributions of Indigenous knowledge, science and political thought. The event also focused on recognizing the importance of Indigenous people for the future instead of simply framing them in the past.

The event opened with remarks from Mrinalini Sinha, event moderator and director of the EIHS. Sinha said the EIHS has worked extensively to foster a setting where individuals can participate together in vigorous intellectual exchange, as displayed by this symposium and other discussions.

“The inspiration for this event was a part of our year-long theme of recovery,” Sinha said. “We were wanting to think about the future, but not in a kind of linear way but rather by overcoming events from the past. On the issue of climate justice, for example, more privileged people probably think of the environmental disaster as a future event. But Indigenous people have watched the extinction of species and seen environmental disasters committed for centuries and have figured out ways to adapt to it, which we can learn from.”

Ana María León, assistant Art History professor, began with a discussion of the legal framework of Indigenous thought and said the Constitution gives people the ability to litigate the ecosystem on behalf of their personal gain, which consequently leads to environmental degradation.

“Environmental entities should realistically give people the ability to advocate for their environment and outdoor space,” León said. “However their actions, both on the left and right, are solely political. … The vast resources of capital that could be used to protect the environment have no bearing if the state decides to go another way.”

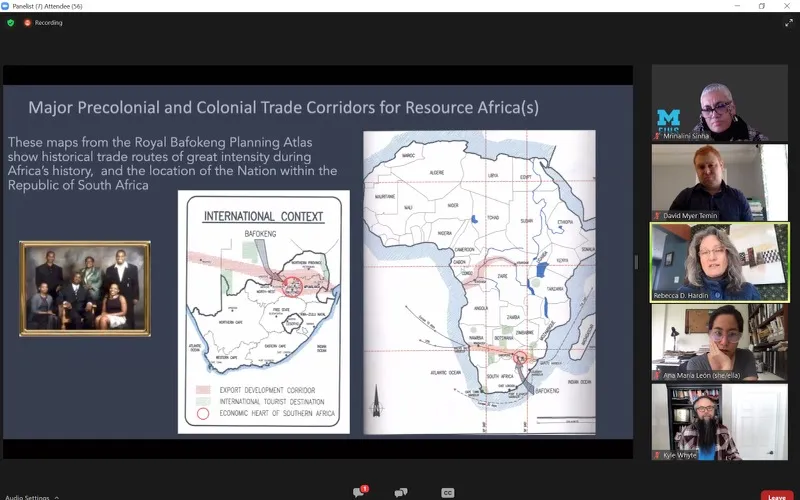

Sinha then redirected the conversation to Rebecca D. Hardin, associate professor atU-M’s School of Environment and Sustainability. Hardin, who has conducted research in South Africa, said her work was eye opening, particularly her analysis of the Royal Bafokeng Nation.

“When I saw the inner workings of the Bafokeng Nation, I was in awe,” Hardin said. “The champagne flutes and Christian Dior suits were a deft and creative combination of not only their sartorial forms but also their governance form … these strategic acts are in danger of colonial romanticization.”

Kyle Whyte, a professor in the School of Environment and Sustainability, then spoke on his work in the climate change sector of Indigenous people.

“All that the term climate change indicates, is that people who have been sheltered against colonialism now think that they may have something to lose,” Whyte said. “But, (Indigenous people) have faced years and years of climate and environmental chaos that we have adapted to and if these methods are employed, people may not lose as much as they think.”

When asked about land defense strategies and government change, Whyte said it is relevant to compare the past and the present. He shared information about a tribe in Oklahoma in the early 20th century, the same tribe’s situation today and his perspective on what should be done in response to the changes.

“The tribes were dealing with environmental change that they didn’t cause, and their lands were in the process of being liquidated,” Whyte said. “Land was going unstewarded and the U.S. government was forcing them to adopt democratic processes. We’re engaging in land defense, seeking to take back our government and make our own decisions about technology infrastructure.”

David Myer Temin, assistant professor in political science, said his side of the discussion aligned with an overview of the Land Back Movement — a movement aiming to return ownership of Indigenous lands to Indigenous communities.

“Land Back is not new,” Temin said. “These are movements that trace back to the onset of European colonization. When many Indigenous people talk about land back, what’s implied is not the reassertion of ownership of land as a commodity but the reassertion of the relationship between the people and the land which can be multiscalar.”

León then talked about the experience in urban and regional planning from the Indigenous peoples point of view.

“In my class, I would teach the ways in which a territory is structured,” León said. “There is always a lot of frustration among my students as they try to think of solutions in feasible ways to operate a territory. We operate in this world where our moves do wrong and we need to maneuver more mindfully within that space.”

Temin closed the symposium with his understanding of the Green New Deal and the overlapping features it has with the work done by Indigenous people.

“The Green New Deal, framed as a national jobs program, is essentially an economic development program,” Temin said. “Reality is, that if we’re talking about green jobs, what they did at Standing Rock was a green job. It was a green job that they tried to criminalize as terrorism under thePatriot Act. Most of the jobs that are ‘green’ are jobs that are already taken up by racialized populations.”