In 1938, a Ukrainian-born grandmother created one of art’s biggest shocks – but it was attributed to the US painter Jackson Pollock, writes Kelly Grovier.

This is the way the story has always been told: in 1947, Jackson Pollock, the pioneering American painter whose rugged name rhymes with the verve of his virile persona, finally lost patience with the fussy finesse of careful brushstrokes that had defined art history. Chucking his bristles and easel aside, he grabbed some sticks and started flinging paint directly on a canvas he’d stretched out on the floor. With a flick of his wrist while galloping around the work like a ranch hand roping a rampant calf – not so much painting a passive image as lassoing an untamable one – Pollock had hit upon a fresh new mode of energetic artistic expression, one with muscle and swagger befitting the wild west of his Wyomingite birth and the wide, dry lightning plains of his unbridled psyche.

“During the summer of 1947,” Camille Paglia writes in her excellent survey of milestones in the history of image-making, Glittering Images: A Journey Through Art from Egypt to Star Wars, “there was a major breakthrough: he invented his signature ‘drip’ style, which would transform contemporary art.” Pollock’s was an instinctive, shoot-from-the-hip technique that didn’t painstakingly plot its next move – rather, one that grabs a bottle, takes a swig, wipes its lips on its cracked knuckles, and couldn’t care less who’s watching. This is painting free from form and formalities, the kind of painting that only an American, a real American, could invent.

Only it wasn’t. Contrary to established myth – a myth accelerated by sensational spreads in Time and Life magazines in 1949 and 1956 under such eyebrow-raising headlines as “Jack the Dripper” and “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” – Pollock’s “signature” style wasn’t his invention at all, but the brainchild of another artist, one whose extraordinary story confounds and invigorates our understanding of one of the most celebrated contours in recent cultural history. Put simply, modern art has a problem. Her name is Janet Sobel.

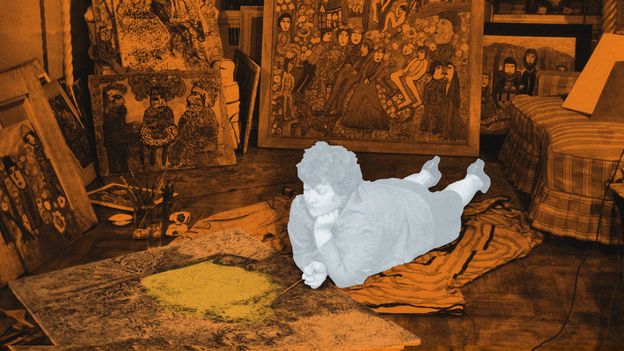

The true story of the birth of both the “drip” technique and so-called “all-over painting” (in which the surface of a work is approached holistically from every direction), is no less remarkable than the famous fable: in 1938, a 45-year-old Ukrainian-born grandmother, with no previous artistic training, began fiddling around with her son’s painting supplies and changed the course of cultural history. Born Jennie Lechovsky in a Jewish town in eastern Ukraine in 1893, Sobel escaped the violence of anti-Semitic pogroms (in which her father had been killed), and arrived in New York with her mother and three siblings in 1908, when she was 15. Much of the next three decades would be devoted to the rearing of five children who she had with Max Sobel, an engraver and goldsmith, whom she married the year after she reached Ellis Island. It was only when their 19-year-old son Sol, frustrated with his own artist development, palmed off his supplies to his mother in the late 1930s that Sobel herself began to experiment with making paintings.

“One story has it,” according to the art historian Gail Levin, “that she began to draw on top of some of the drawings that Sol brought home from his art classes… Another is that Sol, while still in high school, had won a scholarship to the Art Students League, which, against his mother’s wishes, he sought to give up. When she tried to convince him to continue, he reportedly exclaimed: ‘If you’re so interested in art, why don’t you paint?'”. She was a natural. Without any instilled deference to rules that mustn’t be broken – and with the fearlessness of someone who had survived the traumas of religious persecution and the hardships of the Great Depression – Sobel unselfconsciously set about inventing art as if entirely from scratch.

‟ She assaulted the surface of canvases laid out on the floor, orchestrating a liquid lyricism of spills, splashes and spits the likes of which had never before been seen

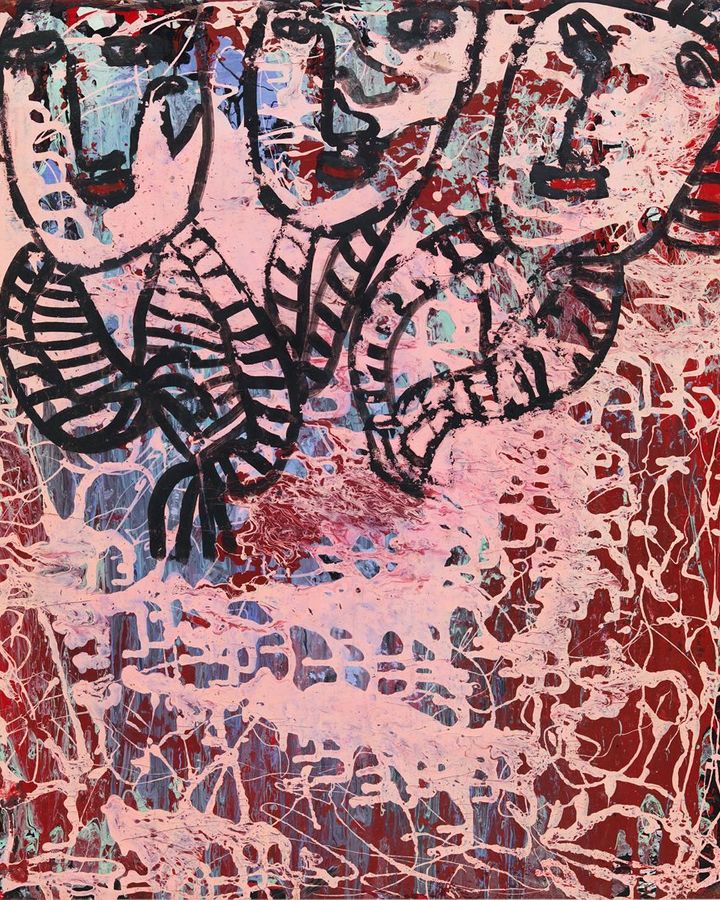

The first flush of works is characterised by a primitivist poetry of dreamlike forms floating in enchanted landscapes with a levitational allure that recalls the mystical visions of Marc Chagall, whose own fierce folkloric imagination had been forged by the violence of pogroms. But it isn’t long before figurative storytelling gives way to a more ambiguously amorphous cadence of expression that strayed beyond Surrealist impulses to pure abstraction. With no inculcated allegiance to any artistic school or prejudice regarding the appropriateness of materials, Sobel began playing both with what a painting can say and how it can say it. Using unconventional implements such as glass eye-droppers to squirt paint and the strong suck of a vacuum to drag wet splatters into thin gossamers that no traditional brush could spin, she assaulted the surface of canvases laid out on the floor, orchestrating a liquid lyricism of spills, splashes and spits the likes of which had never before been seen.

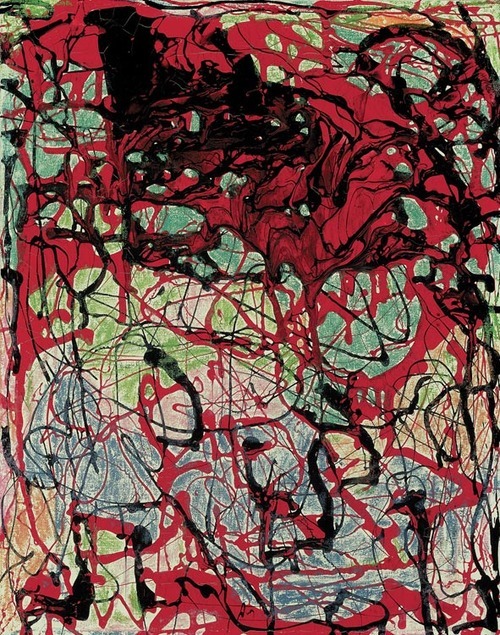

The result was works such as Milky Way, 1945 – a silent symphony of delicate enamel whorls and surging spatters that Sobel created two years before Pollock would fling his first skirl of paint or began producing his own inchoate cosmic sonatas such as Galaxy (1947). Some creative coincidences can be chalked up to the untraceable synergies of zeitgeist – contemporaneous imaginations incidentally synchronised to the same cultural stimuli. This isn’t one of them. Pollock was profoundly influenced by Sobel’s work, and history has saved the receipts. Almost as quickly as Sobel had begun to experiment with making images, her son Sol set about attracting attention to her remarkable efforts, reaching out to everyone from Chagall himself to the influential art collector Sidney Janis, who would prove instrumental in establishing the reputations of everyone from Willem de Kooning to Mark Rothko to Pollock.

By 1944, Sobel was well on her way to being a formidable fixture in the New York art scene, debuting that year with a solo show at the Puma Gallery on 57th Street – an exhibition that yielded widespread praise for her works’ “astounding sophistication” and “absolutely unrestricted” imagination. Janis (who predicted that Sobel “will probably eventually be known as one of the important surrealist artists in this country”), included her work in a prominent exhibition Abstract and Surrealist Painting in America that toured the country that year.

Soon after, Sobel’s profile was given a further boost in 1945, when the legendary art promoter Peggy Guggenheim included her in a prominent exhibition, The Women, at Guggenheim’s Art of the Century gallery, before offering Sobel her own solo show the following year – an event that incontestably would bring her innovative practice and paintings (if they had not already) to the consciousness of Pollock. Writing years later in 1955, the art critic Clement Greenberg admitted to visiting the exhibition with Pollock and that the two “noticed one or two curious paintings shown at Peggy Guggenheim’s by a ‘primitive’ painter, Janet Sobel (who was, and still is, a housewife living in Brooklyn)”. Putting to one side Greenberg’s derisory instinct to belittle the status and achievement of Sobel (“curious”, “primitive”, “housewife”), what he goes on to acknowledge places beyond doubt the enduring significance of the encounter: ‘Pollock (and I myself) admired these pictures rather furtively… The effect – and it was the first really ‘all-over’ one that I had ever seen… – was strangely pleasing. Later on, Pollock admitted that these pictures had made an impression on him.”

Why “furtively”? It is, after all, a word that admits a level of guilt and secrecy to the act of looking. Despite Pollock’s own admission that Sobel’s work “had made an impression on him”, Greenberg can’t resist diminishing the magnitude of that acknowledged impact. Greenberg goes on to insist that when Pollock “began working consistently with skeins and splotches of enamel paint, the very first results he got had a boldness and breadth unparalleled by anything seen” in the work of any previous painter, including Sobel. “Even as he selects Sobel as Pollock’s predecessor,” notes the art historian Sandra Zalman, “Greenberg asserts that Pollock had already surpassed her.”

Fortunately, we have more to measure the “boldness and breadth” of the two artists’ respective achievements – at this formative stage in the unveiling of the drip technique – than Greenberg’s suspiciously “furtive” assessment. Placed side-by-side with Sobel’s earlier painting Milky Way, Pollock’s Galaxy is murky and muddled, like someone still searching for his voice or burying it under lashings of doubt. After all, Pollock’s painting is, literally, a cover up. “At first, in a picture such as Galaxy,” explains his biographer Deborah Soloman, “Pollock spattered paint to obscure an image that had begun as a human figure.” For Sobel, the invention of drip painting was a ritual of self-revelation. For Pollock, at least initially, the technique was imitative and self-concealing: a mask.

Whatever one’s estimation of the relative merits of Sobel’s and Pollock’s work at this moment in the unfolding narrative of modern art, as history would have it, Pollock would prove to be in the far stronger position to advance the technique of drip painting, whether it was his invention or not. Just as Sobel was gaining traction as a creative force in New York – no small feat for a female artist of her or any generation – her circumstances suddenly changed dramatically, and in ways that effectively removed her from the world of art completely. In 1946, the same year that she opened a solo show at Guggenheim’s Art of the Century gallery, her husband Max, moved the family from Brooklyn to Plainfield, New Jersey, in order to be nearer to his costume jewellery enterprise. Unable to drive, Sobel quickly found herself cut off from the ebb and flow of the art scene in which she had only just become an important player.

Compounding that geographic disadvantage was the decision taken the following year by her biggest advocate, Peggy Guggenheim, to relocate to Europe, closing behind her the doors of the Art of the Century gallery – Sobel’s principal platform. Adding insult to injury, the onset of an allergy to an ingredient in paint forced Sobel to turn instead to media such as crayons that were less conducive to the drip technique, all but forcing her to abandon the innovation entirely. By 1948, Janet Sobel, who would die in obscurity 20 years later, had effectively vanished from the art world. Though not without a trace. Her enduring genius can still be mapped in the innumerable knots and infinite coils of pigment with which Pollock will proceed to intertwine his more famous canvases – endlessly weaving her spirit into the tangled firmament of art history.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to ourFacebookpage or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story,sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.