The anniversary of an 1865 announcement by a Union military official in Texas has grown over the years into a celebration of emancipation – the end of slavery in the United States.

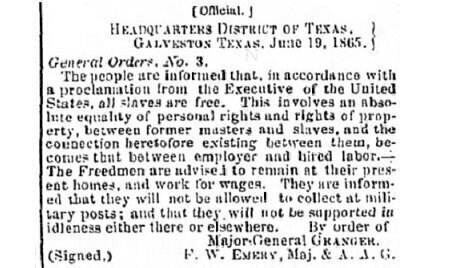

On June 19, 1865, Major General Gordon Granger issued a general order in Galveston, Texas. Granger’s biographer, Robert Conner, believed the order was read aloud in public from a local hotel.

On June 19, 1865, Major General Gordon Granger issued a general order in Galveston, Texas. Granger’s biographer, Robert Conner, believed the order was read aloud in public from a local hotel.

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves and the connection heretofore existing between them, becomes that between employer and hired labor. The Freedmen are advised to remain at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Newspaper accounts of General Order 3 indicated the words “all slaves” were emphasized in italics.

In reality, President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, was a direct order from the chief executive to free enslaved people in all states taking part in the rebellion against the federal government, including Texas. And General Granger’s order came roughly two months after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his troops in Virginia. That did not mean the federal government had the ability to enforce the order widely or the news made it to many people in Texas. But after the Civil War ended, Granger’s order had the effect of informing Texas residents that slavery had ended in their state, including enslaved people who had not been told by their masters.

On December 6, 1865, the 13th Amendment was ratified and extended the prohibition on slavery beyond the former rebellious states, saying that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

Scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. said General Order 3’s immediate impact was delayed. “On plantations, masters had to decide when and how to announce the news — or wait for a government agent to arrive — and it was not uncommon for them to delay until after the harvest,” Gates wrote in an article for The Root in 2013. Violence against newly freed Black people also occurred, Gates noted.

In the Congressional Research Service’s recent guide to the Juneteenth holiday, the service says that unofficial Juneteenth celebrations started in Texas’s Black community the following year. “Texans celebrated [the Juneteenth anniversary] beginning in 1866, with community-centric events, such as parades, cookouts, prayer gatherings, historical and cultural readings, and musical performances,” the CRS recounts.

Over time, the Juneteenth holiday was celebrated outside of Texas in the South and other parts of the country. A 1949 reference in the journal American Speech indicated that Juneteenth was the day Black community members “in the South commemorate the freedom of their race from slavery.”

In 1980, Texas also was the first state to make Juneteenth a state holiday. Today, the Congressional Research Service says 48 states and the District of Columbia commemorate or recognize Juneteenth in some official way. Juneteenth also became a federal holiday in 2021.

As for the word Juneteenth, it is an example of a portmanteau or a word that combines the meaning of several words.