By talking plainly about her qualifications, Harris embodies progress. Will it work?

In her 2019 memoir, The Truths We Hold: An American Journey, Kamala Harris talks about how, during her first run for office—for San Francisco district attorney, in 2002—she taught herself to campaign. The lessons were partly about logistics (carry an ironing board in your car—the ideal portable podium for ad hoc campaign stops). But they were also about unlearning years’ worth of conditioned humility. “I was always more than happy to talk about the work to be done,” Harris writes of her conversations on the trail. The voters, though, wanted to hear about her: her experiences, her principles, her accomplishments. “I’d been raised not to talk about myself,” she says. “I’d been raised with the belief that there was something narcissistic about doing so. Something vain.”

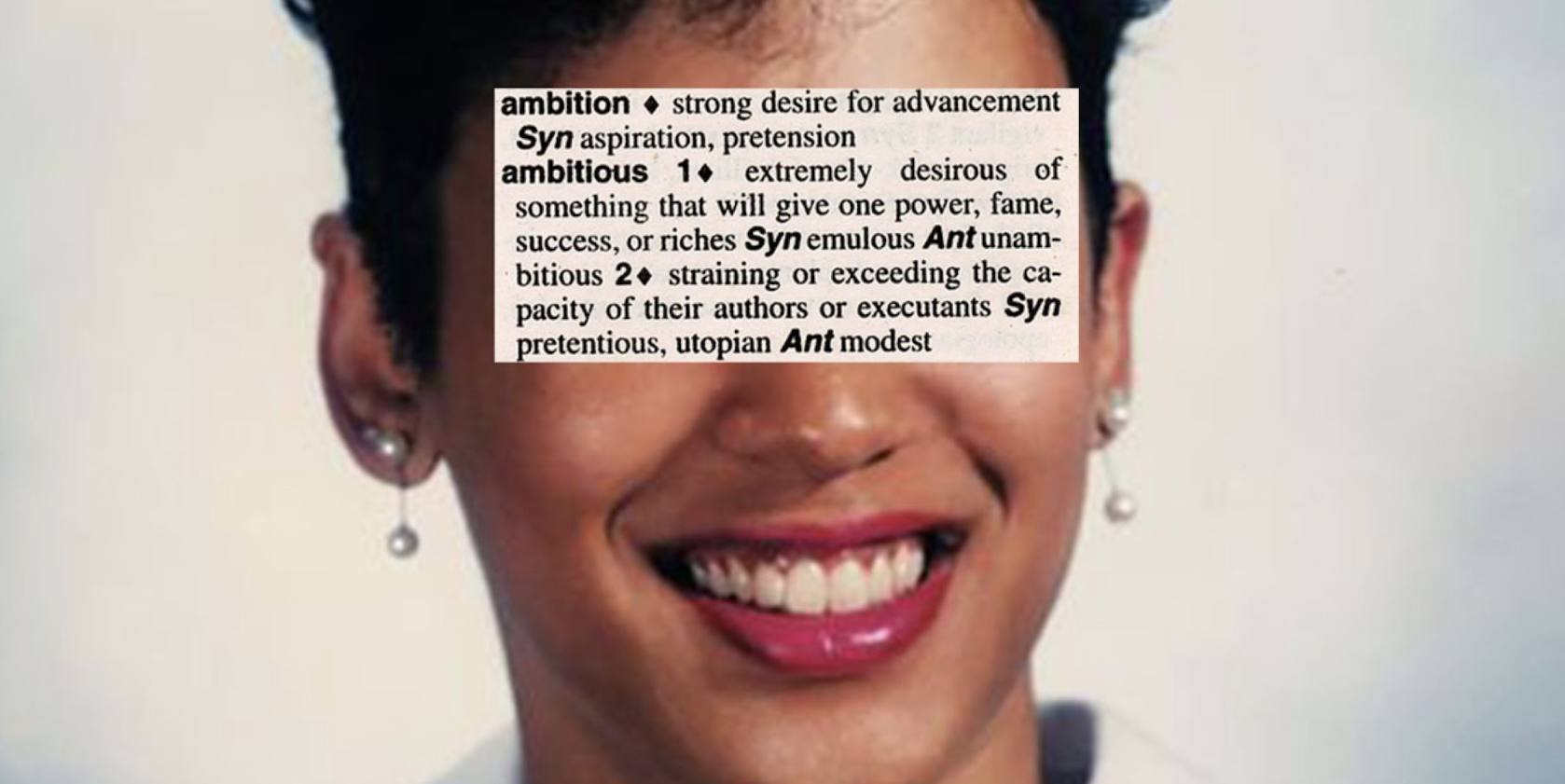

The political memoir is a literary genre that consists mostly of carefully coded humblebrags; here, though, was an insight about bragging itself. Reading it, I felt a pang. American culture is fluent by now in the easy language of female empowerment. One of the 50,485,942 or so pieces of evidence that the rhetoric has outpaced the reality is the idea that women who achieve things aren’t supposed to say so. The sanction goes beyond general-purpose puritanism (self-confidence good! self-importance bad!). It has to do with the fact that, regardless of our own gender, we still tend to view women as self-sacrificial and self-effacing, first and foremost—mothers, basically, whether they have children or not. That’s how you get a situation where Target sells T‑shirts that read she can/she will—and where you can also pretty safely assume that, if you compliment a woman about the thing she did, she’ll reply, “Oh, it was nothing.”

So it was deeply gratifying to watch Kamala Harris, on an evening late in August, make her personal ambition a matter of national interest: She accepted the Democratic Party’s nomination for the vice presidency of the United States. Harris is the first Black woman, and the first South Asian woman, to do so. And she is the first woman to step into the role not as a human version of a Hail Mary pass—not in an attempt, with apologies to Geraldine Ferraro and Sarah Palin, to revive a struggling presidential campaign—but as a fully vetted and viable contender for the White House. Come 2021, if Kamala Harris is one heartbeat away from the presidency, she will be prepared for the proximity.

In the speech she gave at the virtual Democratic National Convention, Harris praised the people who’d paved the way for her elevation: Mary Church Terrell and Mary McLeod Bethune, Fannie Lou Hamer and Shirley Chisholm. She praised Joe Biden. She praised her mother. And she praised herself. “I’ve fought for children and survivors of sexual assault,” the former prosecutor said, introducing herself to the voters who were not yet familiar with her story. “I’ve fought against transnational gangs. I took on the biggest banks.”

[From the May 2019 issue: Kamala Harris takes her shot]

Watching her speech, I felt another pang—this time, of joy. That evening, for the first time, millions of Americans were able to look at a candidate for the White House and see someone who looked like them. New possibilities unfurled. Harris was selling herself as a leader to a country in dire need of one: The coronavirus pandemic was raging on, and the summer had throbbed with reminders that the phrase Black lives matter remains, for some, an argument rather than a statement of fact. But by talking about her qualifications for power without qualification, Harris embodied progress. She closed out her speech to the music of Mary J. Blige’s “Work That.”

The swaggering lyrics served as a tidy rebuke to the perverse flurry of news stories that had been written about Harris all summer—stories that treated her political successes as evidence against her elevation. “She seems not loyal at all and very opportunistic” (CNBC). She’s “a little too charismatic”; “she might be a little bit dominant with her personality” (Bloomberg). She can “rub people the wrong way” (CNN, quoting Ed Rendell, the former governor of Pennsylvania and a close friend of Biden’s). Politico, in a widely circulated piece, reported that Chris Dodd, a member of Biden’s vice-presidential search committee, was miffed that Harris had shown “no remorse” about the primary-season debate in which she’d discussed the impact of Biden’s opposition to school busing. “That little girl was me,” Harris had said, creating one of those instantly iconic lines that politicians strive for. To Politico, this wasn’t an example of one debater scoring a point on another—it was an “ambush.”

Empowerment! say the shirts and the signs. However! says everything else. “Half the Men in the U.S. Are Uncomfortable With Female Political Leaders,” a 2019 HuffPost headline reads. That stat helps explain why American media are out there claiming that the best measure of a woman who seeks the vice presidency is her lack of desire to be president. Representative Karen Bass of California, another Black woman whom Biden considered for VP, was lauded in the press as the “anti–Kamala Harris,” and for allegedly harboring only “muted ambitions.” A 2010 article in a psychology journal describes the process by which female ambition is weaponized: The pursuit of power “may signal to others that she is an aggressive and selfish woman who does not espouse prescribed feminine values of communality.” In another journal, two psychologists explained how they’d been inspired to write an article about the cultural enforcement of “modesty norms”: They’d issued a call asking fellow female faculty members to share their success stories for a planned campus publication—and did not receive a single personal story. Instead, women wrote to tell them about other women who deserved to be featured.

Oof. Another pang. Bragging—not just in politics, but in American society at large—is a foundational skill. To get the job, any job, you need to be able to speak well of yourself. To rise, you need a little hot air. Unsurprisingly, ambition-aspersions seem to be directed at women of color with special vehemence. At the Black Girls Lead conference this summer, Harris recounted the insults that have trailed her like exhaust as she’s risen to power—and Haley Taylor Schlitz, a teenager who attended the conference, thinks she knows why. Pundits “do not fear Senator Harris for her ambitions,” Taylor Schlitz wrote. “They fear her because of a generation of Black girls who are watching and [who] will follow her example to pursue excellence.”

[From the October 2018 issue: Fear of a female president]

Not long after Harris told the young women at that conference, “I want you to be ambitious”—and not long after Representative Ted Yoho of Florida referred to his colleague Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez as a “fucking bitch” on the steps of the Capitol—Ocasio-Cortez shared a video with Vogue. The topic: her beauty routine. The purpose: to celebrate feminine self-confidence. “Our culture is so predicated on diminishing women and preying on our self-esteem,” the New York congresswoman said as she dabbed on under-eye makeup. “And so it’s quite a radical act—and it’s almost like a mini-protest—to love yourself.”

Bitch became part of the American vernacular to describe unruly women during the campaign for female suffrage. The use of the term more than doubled from 1915 to 1930, Vice reports, even as some suffragists strove to cast their quest for the vote not as a righteous crusade for equal political empowerment but as the logical extension of their social partnership with men. “You ask us to walk with you, dance with you, marry you,” one poster put it. “Why don’t you ask us to vote with you?”

The specter of the bitch has lived on in American politics. Geraldine Ferraro, Walter Mondale’s running mate in 1984, found herself dismissed by George H. W. Bush’s press secretary as “too bitchy” for the No. 2 job. The critiques of Ferraro, and of Sarah Palin during the 2008 election cycle, didn’t always summon fears of Lady Macbeth—sometimes the goal just seemed to be to push the ladies back into their rightful place. Remember all the breathless stories about Palin’s figure, and her glasses and wardrobe? Ferraro was asked, at a campaign stop, whether she could bake blueberry muffins. Even some of Mondale’s aides, Ferraro later said, were so condescending to her that she suggested that whenever they looked at her, they should “pretend” that she was “a gray-haired southern gentleman, a senator from Texas.”

[Read: Hillary Clinton, Tracy Flick, and the reclaiming of remale ambition]

The vice presidency is a job of complementary angles; its occupant serves at the pleasure of the person who inhabits the Oval Office. This is in large part why so many of the men in the role have resented it. John Adams, writing to his wife, Abigail, called the vice presidency “the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived.” The editor of The Nation, E. L. Godkin, derided the vice-presidential nomination of Chester A. Arthur, a machine politician trailed by allegations of corruption, on the following grounds: “There is no place in which his powers of mischief will be so small as in the Vice Presidency.” Thomas R. Marshall, Woodrow Wilson’s veep, likened the vice president to “a man in a cataleptic fit: He cannot speak; he cannot move; he suffers no pain; he is perfectly conscious of all that goes on, but has no part in it.”

Here are some dudes, in other words, who have an inkling of what it can feel like to be a woman.

Consider again, then: Even as Kamala Harris sought a job that has been defined by its lack of power, people found ways to complain that she was seeking too much power. Forward movement can feel a lot like whiplash. Harris is the first woman of color to seek the White House on a major-party ticket; that is cause for celebration. But the milestone is also, at this point, cause for indignation: It took this long? Really? Harris, as it happened, accepted her party’s nomination during the week that marked the 100th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment’s ratification. The coincidence was poignant. It provided an opportunity to contemplate how much has changed, over the long American century, and how much has not. The answer is: A lot. And, still, not enough.

This article appears in the November 2020 print edition with the headline “Oh, It Was Nothing.”