The proposal has divided the community, including those who had been allied in calling for police reform after Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd last year.

MINNEAPOLIS — Three weeks before Election Day in the city’s municipal races, Candis McKelvy attended a debate about a ballot initiative to replace the Minneapolis Police Department with a Department of Public Safety.

She listened intently for 90 minutes as a representative from Yes 4 Minneapolis, the coalition that petitioned to put the item on the ballot, and a supporter of All of Mpls, which opposes the measure, tried to pull residents to their respective sides.

By the night’s end, McKelvy was stuck in the middle.

“I’m on both sides,” said McKelvy, a North Minneapolis resident in her 60s who was among the roughly 250 people at North High School, where the debate was held.

She agrees with the measure’s proponents that the city’s police department is broken and in desperate need of an overhaul. But she fears that revamping it would mean losing the city’s popular Black police chief.

“I need one more piece of information,” she said as she left the debate. “If I vote no, then do things just stay the same?”

That question is on the minds of many Minneapolis residents as they grapple with how to vote Nov. 2 on one of the first major tests of the national police reform movement since George Floyd’s death last year.

The measure before them, Question Two, would amend the city’s charter to get rid of the police department and replace it with an agency that provides a “comprehensive public health approach” to public safety. The specifics of that department, including who would serve as its commissioner, would be decided later by the mayor and City Council.

Supporters of the proposal say it would bolster public safety to include not just police officers but also mental health and substance abuse experts, violence interrupters and others better suited to handle situations that armed police officers ordinarily face. The goal is to reduce the role of police in calls involving homeless people, mental health issues and substance abuse, said JaNaé Bates, a spokeswoman for Yes 4 Minneapolis.

But opponents have seized on the vague wording and newness of the ballot initiative to encourage residents to vote against it, suggesting that it would effectively “defund” the police and fail to address violence in the city.

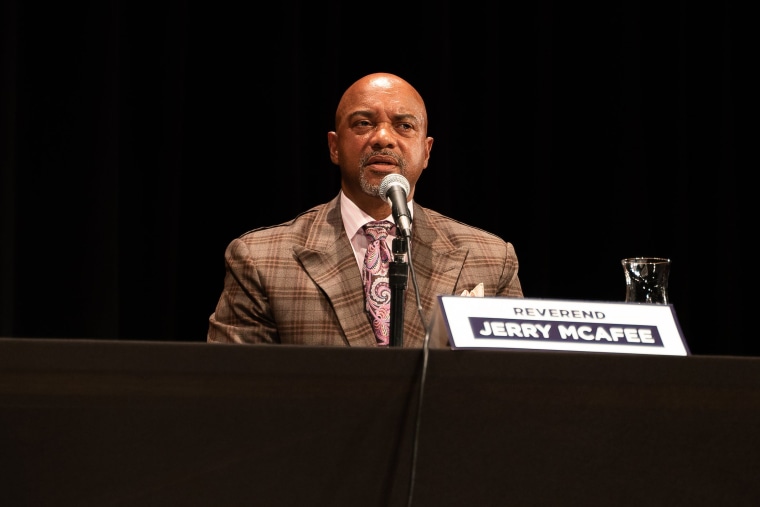

“It raises more questions than it gives answers,” said the Rev. Jerry McAfee, a pastor at New Salem Missionary Baptist Church, who represented the “no” vote during the debate.

The proposal has divided the community, including those who previously had been aligned in calling for changes in policing after Floyd was killed by former Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvinin May 2020. It also has divided some of the state’s top Democrats. Rep. Ilhan Omar and Attorney General Keith Ellison, for example, support the plan, while Sen. Amy Klobuchar, Gov. Tim Walz and Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey, who is running for a second term, oppose it.

‘Let’s try something different’

Demonstrators began pressuring Minneapolis to overhaul its police department last year shortly after Floyd’s death sparked a reckoning against police brutality and racial injustice. The request drew early support from a majority of the City Council who already had been calling for reform.

City Council member Steve Fletcher said Floyd’s death “accelerated the conversation quite a lot.”

Yes 4 Minneapolis, a coalition of more than 100 businesses and organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union of Minnesota, said it gathered more than 20,000 signatures to get the measure on the ballot. Minneapolis has a population of roughly 430,000 and as of mid-October, 591 officers.

The council, which would get more control over law enforcement and public safety if the measure passes, approved the ballot language in July, and after it was challenged, the state Supreme Court last month cleared the way for voters to consider it.

Minneapolis is among a number of municipalities considering or trying to overhaul its police department, an outgrowth of calls to “defund” the police following Floyd’s death.

The ballot measure says the new department “could include” police officers “if necessary.” It does not include the word “defund,” but critics say the measure is intentionally vague so as to conceal its goal to do so.

“I’ve been really challenging everybody to get past the word,” Fletcher said. “Pick whichever word you want. Reimagine, transform, defund, disband, restructure, reinvest, whatever the word is that works for you … and focus on what would it do and what we actually have to change together.”

A recent poll of 800 likely voters found that 49 percent of those surveyed supported replacing the police department and giving the City Council more authority over public safety; 41 percent opposed and 10 percent were undecided, according to the poll, which was conducted by NBC affiliate KARE 11, The Star Tribune, Minnesota Public Radio and PBS’s “Frontline.”

The city is dealing with “a known bad status quo” that almost everyone agrees is problematic, said Ellison, who lives in Minneapolis and whose office won a murder conviction against Chauvin. A day after Chauvin’s conviction, the Justice Department announced it was opening a sweeping investigation into policing practices in Minneapolis.

He said residents will have to ask themselves: “‘Do you want to let go of what you know is not great, but you know it? Or reach for something that’s uncertain because it’s in the future, and we haven’t done it yet?’ I’m saying: Let’s have some hope that we can figure this out together as a community. Let’s try something different.”

Council member Cam Gordon, who represents eastern Minneapolis, said the biggest problem the measure would address, if it passes, is oversight of the police department and who gets to determine police policy.

“Right now, it’s the only city department that gives exclusive policymaking authority to the mayor,” he said.

Supporters of the measure have pointed to the police departments in two New Jersey cities — Camden and Newark — as templates for reform.

The police department in Camden, where more than 90 percent of residents are Black or Hispanic, was disbanded in 2013 and then rebuilt despite opposition from police unions and some residents.

“Those communities have said, ‘You know what, let’s reform,'” Ellison said. “But the thing about Newark is, Newark did its changes under a federal consent decree. I’m saying to the people of Minneapolis, let’s not have the federal government make us reform. Let’s just choose it.”

In 2014, the Justice Department reached an agreement with Newark, the state’s largest city, to allow a federal monitor to watch over a police force that it found had repeatedly violated the rights of its citizens, especially Black people, who account for a majority of the population. Newark police officers did not fire a single shot in 2020 or issue any payouts to settle police brutality settlements, The Star-Ledger reported in January. The murder rate has also dropped in Newark in recent years.

‘I don’t want to be another test case’

Critics of the Minneapolis measure, however, said it has too many unknowns.

“We don’t know what it will do,” McAfee said during the debate. “We can’t even really answer the questions, because I don’t know where it’s ever been done.”

“And I don’t want to be another test case,” he added.

Minneapolis is the only city in Minnesota required by its charter to have a minimum amount of officers, a civil rights era requirement, said City Council member Phillipe Cunningham, who represents the northernmost part of Minneapolis and supports the measure.

Passage would not “abolish” the police or lead to the firings of any officers, as critics have claimed, Bates said.

Still, the prospect that replacing the police department would put Police Chief Medaria Arradondo’s job in jeopardy has become a deciding factor for many voters. Arradondo, a Minneapolis native who fired Chauvin and testified against him in his murder trial in the killing of Floyd, has broad popularity.

Cunningham said that All of Mpls has framed the ballot measure around Arradondo to capitalize on his popularity.

“This constant going back to the chief is meant to be a distraction because we should not be talking about one man when we’re talking about a systemic failure,” Cunningham said. “A question that needs to be answered is: Will the chief renew his contract? We already know that he was applying to other jobs this year because he was a finalist in San Jose for their police chief position before that went public and then he withdrew his name.”

Arradondo, who has been with the department for more than 30 years, has criticized the proposed amendment, saying the appointment of a new public safety commissioner who reports to the mayor and City Council “would be a wholly unbearable position for any law enforcement leader or police chief.”

Like Cunningham, Fletcher believes residents “cannot make structural decisions” about the city based on individual people.

“If any of this relies on a particular mayor or a particular chief, or particular council members, then we’re failing to think about the structure of our government because it has to be a structure that can endure for many, many mayors, and many, many chiefs and many, many councils in a way that produces better outcomes,” Fletcher said.

A community divided

When All of Mpls canvassers arrived at Yasmin Abdi’s home this month, she informed them that she would be voting against the measure. She said she welcomes adding social workers and mental health experts to the city’s public safety ranks, but still wants the police department to have a major presence.

“If they want to work alongside the police officers, they could do that,” Abdi, 28, said. “Because things could get violent real quick.”

Residents like Abdi said they fear that if the amendment passes, it will take away from the police while violent crime is an issue and the police department is dealing with morale and staffing problems. There have been at least 78 homicides so far this year, according to the police department’s crime statistics dashboard. Last year, Minneapolis recorded 83 homicides, the police department said, the second-highest year on record in decades.

McAfee said groups like 21 Days of Peace, a multidenominational effort he founded in May that works with police to reduce crime in the Twin Cities, is better suited to assist with reform.

Jackie Martin, 52, a North Minneapolis resident who went door to door canvassing for All of Mpls, said she doesn’t think mental health experts or social workers should respond to calls without being accompanied by armed officers.

“Our neighborhood is not built for that,” said Martin, a personal care attendant.

But residents like Adriana Surmak, 30, who said she is voting yes on Question 2, said the police department is not functional in its current configuration.

“It’s not adding a layer of safety to the city that in any way outweighs the harm that it does in communities,” she said.