He was a passionate Jesse Jackson delegate at the 1984 Democratic National Convention and, later, a mentor to future politicians like Senator Cory Booker.

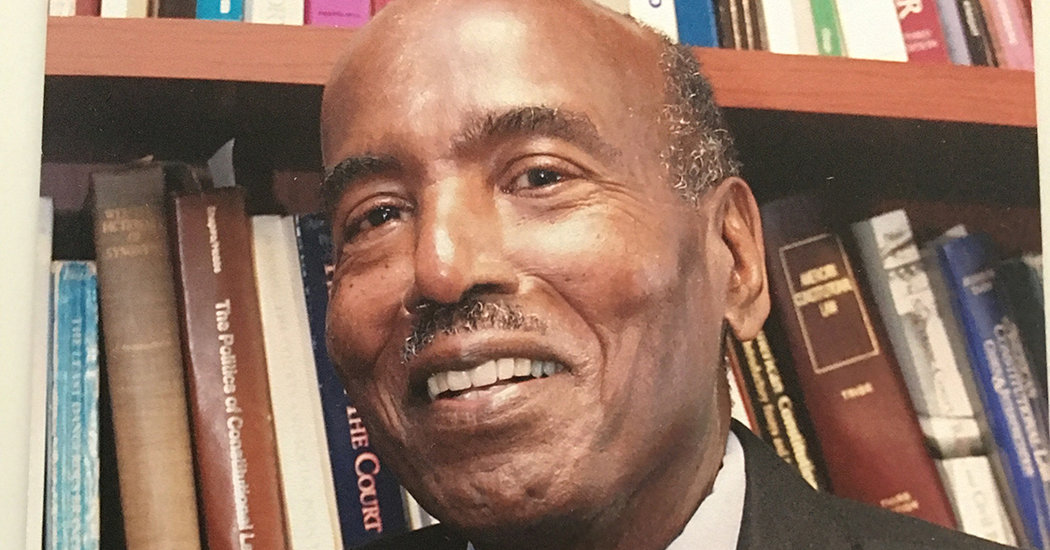

Lucius J. Barker, a revered political scientist and professor whose professional expertise in race in American politics informed his personal role as a delegate for Jesse Jackson at the 1984 Democratic National Convention, died on June 21 at his home in Menlo Park, Calif. He was 92.

His daughters, Heidi Barker and Tracey Barker-Stevens, said the cause was complications of Alzheimer’s disease.

Professor Barker was teaching at Washington University in St. Louis when he joined Mr. Jackson’s presidential campaign. He was known as a popular, if tough, political science professor with scholarly interests in constitutional law, civil liberties and the political impact of race.

To Professor Barker, Mr. Jackson’s campaign represented an extraordinary chance for African-Americans to participate in the political process and “another opportunity to work for the objectives for which Martin Luther King and others fought and died,” he wrote in “Our Time Has Come: A Delegate’s Diary of Jesse Jackson’s 1984 Presidential Campaign” (1988).

As Professor Barker contemplated entering the local caucus in Missouri that led to his selection as a delegate, he thought that being part of Mr. Jackson’s campaign would be an objective academic pursuit that would help his continuing research into race and politics.

But he did not stay a neutral observer for long. He wrote that he was disappointed that February when Mr. Jackson used the term “Hymie” to refer to Jews, but accepted his apology. And, he later wrote, as the convention in San Francisco opened he morphed from a “cloistered scholar to an open activist delegate.”

In his book, Professor Barker described being upset that some Black leaders supported the party’s eventual nominee, former Vice President Walter F. Mondale, and tearful as he listened to Mr. Jackson’s stirring convention speech.

“What makes ‘Our Time Has Come’ stand out are Mr. Barker’s personal observations,” in particular “the pride he personally and Blacks generally felt in having a Black man run a serious race for his party’s presidential nomination,” David E. Rosenbaum wrote in his review in The New York Times.

Professor Barker would later work as a volunteer for Barack Obama’s two presidential campaigns and attend President Obama’s first inauguration, in 2009.

Lucius Jefferson Barker was born on June 11, 1928, in Franklinton, La., about 60 miles north of New Orleans. His father, Twiley Barker Sr., was a teacher and principal at a Black high school in Franklinton. His mother, Marie (Hudson) Barker, taught elementary school there.

“There was a Black and white side of town; white schools, Black schools — everything was separate,” Heidi Barker said in an interview.

At the historically Black Southern University and A&M College in Baton Rouge, Professor Barker, inspired by a young professor, switched his major from pre-med (his family had hoped he would be a physician like the uncle he was named for) to politics.

After graduating, he earned master’s and doctoral degrees in political science at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, where his brother Twiley Jr. had preceded him.

During one summer while he was in graduate school, Professor Barker went to register to vote in Franklinton and was forced by the registrar to answer questions about the Constitution, including one about the 14th Amendment. Such questions were typical of the obstacles placed in front of Black people in the South to prevent them from registering. But they were easy for him to answer.

According to an account of his career he gave in 1992 to PS: Political Science & Politics, a publication of the American Political Science Association, Professor Barker was confident enough to poke intellectual fun at the white registrar.

When he was asked to explain the due process clause of the 14th Amendment, he said he could not. The registrar was apparently gleeful that he might be able to deny Professor Barker the right to vote. “You don’t know!” the registrar said.

“No, I don’t, and neither does the Supreme Court,” Professor Barker said, citing several cases in which the court had been unable to explain what the clause meant.

Professor Barker was successfully registered. He would later administer the test to his students.

He would endure other racist incidents in graduate school and beyond, like being denied the right to eat at a lunch counter and, when he was a professor, being told by security that he couldn’t park in a faculty parking lot.

Professor Barker began his teaching career as a fellow at the University of Illinois. He then went back to Southern University; moved to the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; and returned to the University of Illinois in 1967 as a professor and assistant chancellor. In 1969 he joined Washington University, where he served for a time as chairman of the political science department.

In 1990 he left for Stanford University, where he was also chairman of the political science department. Michael McFaul, who was hired by Professor Barker and would be appointed United States ambassador to Russia in 2012, called him a “giant in political science” in a post on Twitter after his death, adding, “We could use his wisdom and insights right now.”

Judith Goldstein, chair of Stanford’s political science department, described Professor Barker in an interview as “an Old World gentleman” who “cared about the law and about minority interest in the law way before Black Lives Matter,” adding, “In that way he was pathbreaking.”

Among Professor Barker’s published works are two textbooks: “Civil Liberties and the Constitution” (1970), which he edited with his brother and closest friend, Twiley Jr., and “Black Americans and the Political System” (1976), written with Jesse J. McCorry. That book was later revised and republished as “African Americans and the American Political System.”

ADVERTISEMENTContinue reading the main story

He also served as president of the American Political Science Association in the early 1990s. He was the second Black person to hold that position, nearly 40 years after the first, Ralph Bunche, the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize winner.

In addition to his daughters, Professor Barker is survived by two grandsons. His wife, Maude (Beavers) Barker, died in May.

At Stanford, Professor Barker’s students included future politicians like Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey and the twin brothers Julián Castro, a secretary of Housing and Urban Development under Mr. Obama, and Joaquin Castro, a congressman from Texas.

Senator Booker recalled Professor Barker as an uncompromising and rigorous mentor.

“He showed me that there could be a convergence of activism, politics, social and racial justice and academia into a life of profound purpose and impact,” Senator Booker said in an interview. “He stoked my imagination about what I could be, and it wasn’t toward electoral politics; he wasn’t trying to get me to be a mayor or a senator but to be the best sort of an influencer, to bring my best to the world.”