University of Haifa researchers studied over a dozen species of songbirds and were surprised to find female molting patterns are determined by coloring of the males

“Hope is the thing with feathers,” Emily Dickinson wrote. Feathers are the most complex integumentary structures found among vertebrates, and likely the most beautiful as well. Birds use them for thermal insulation, for camouflage, communication and, of course, for aviation.

Like hope, feathers need constant attention. Unlike hair, nails or teeth, feathers do not keep growing. When a feather reaches its full size, it becomes a dead structure. To renew them, birds must shed the old feathers and grow new ones in their place. The process requires a huge investment of energy, which curtails the bird’s other functions as it sheds its entire integumentary structure and generates a new one within a specified period of time.

Despite the importance of molting in a bird’s life cycle, the process has hardly been studied. “Researchers get enthusiastic about studying migration and nesting, but the other important event in the life cycle of birds has been pretty neglected,” says doctoral student Yosef Kiat of the University of Haifa, who has been studying molting for more than a decade.

Birds molt for the first time within one to three months of leaving the nest. In most bird species, the chicks hatch featherless. Young birds head out into the world with relatively low-quality feathers that they grew while still in the nest. Birds want to replace them as quickly as possible with better quality feathers.

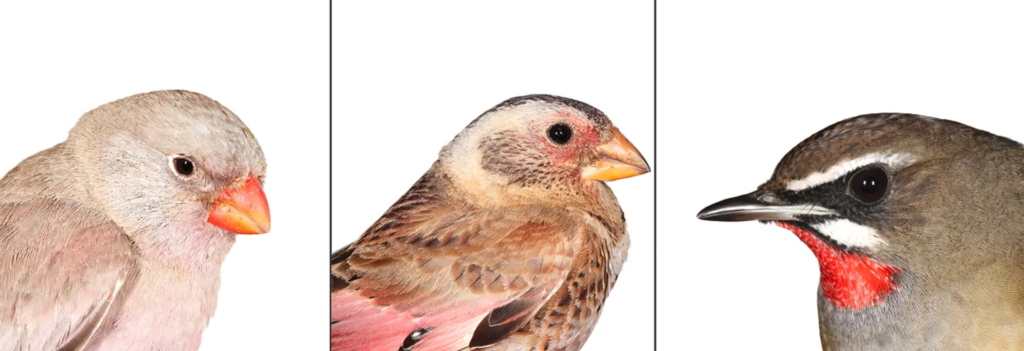

In species where the males are brightly colored (the males are usually more colorful than the females), young birds begin their lives with less colorful feathers. In these cases, early molting comes at a price: The sooner young males grow adult feathers, the more vulnerable they become. The colored feathers, which symbolize reaching adulthood, open them up to aggressive behavior on the part of other males, as well as exposing them to the gaze of predators.

In a recent study, Kiat and Prof. Nir Sapir, head of the Animal Flight Research Group in the Department of Evolutionary and Environmental Biology at the University of Haifa, collected data on about 8,000 young birds belonging to 83 different species of songbirds (the largest and most colorful group of birds). They found that the more colorful a species is, the fewer feathers young males will replace in their first molting outside the nest. That is, during their first feather molting these birds acquire their future coloration only in part. Less colorful species replace more feathers at this time.

The females molt feathers according to the males’ degree of coloration. That is, in species where males only replace a few feathers – due to their color – the females follow suit, even though the females are not brightly colored. The researchers recently reported their findings in the Journal of Evolutionary Biology.

“We found that males dictate fashion,” the researchers said. According to them, it makes sense for colored males to only replace a few feathers. While they do pay a price, as they are forced to make do with lower-quality feathers, they gain improved protection and camouflage. But for females of the same species, it makes no sense. “From what we know at present, females only pay a price for reducing the number of feathers replaced,” the researchers noted.

Following the first molting outside the nest, many species will molt twice a year. During the nesting season, many male songbirds grow colored feathers to prepare for the courtship period. This is a limited replacement, involving mainly the feathers on the torso, which are smaller and relatively easy to replace.

Shortly after the nesting season, the birds undergo a full molting process, replacing feathers all over their body, including the flight feathers. This is necessary, as bird’s feathers often deteriorate during the stressful nesting season. It is an ideal time for molting, as food is plentiful and the weather is still comfortable.

During the full molting process, faded feathers replace colorful ones so that the bird is camouflaged again. According to Kiat, birds that are particularly dependent on their flight capacity will switch between one and three feathers at a time. Birds that live in more protected habitats will replace more than that.

Kiat says the most surprising finding is that the number of feathers replaced across a species is influenced by the male’s coloration, a phenomenon that currently has no explanation. “There are other conditions in nature where the male condition impaces female functioning,” says Kiat. “The common explanation is that female and male members of the same species share an almost identical genome, so there are limitations on the ability to create genetic variation between a male and female of the same species. This sounds like a reasonable explanation,” he says. “The male would pay a higher price for replacing many feathers at once, than the female pays for replacing fewer feathers. Therefore, at the species level, the balance fell in the male’s direction. However, at this stage, it’s only a hypothesis.”