Because of his work, society began to accommodate those who kept kosher and observed the Sabbath.

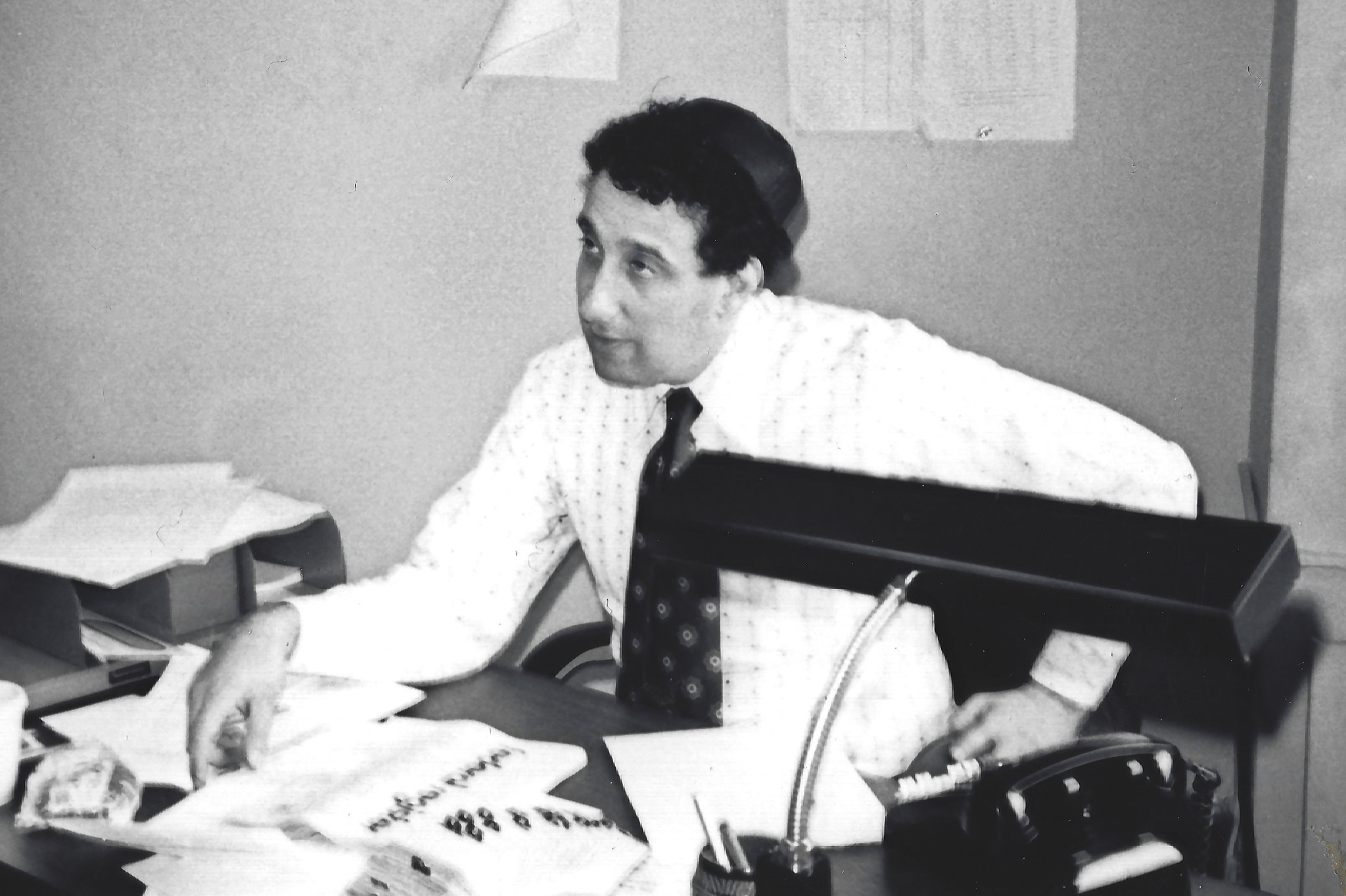

Marvin Schick, a pioneering advocate for the rights of Orthodox Jews to maintain their religious practices in the places they worked, died on April 23 at his home in Brooklyn. He was 85.

The cause was a heart attack, his son Avi said.

Mr. Schick grew up in an America where Orthodox Jews often faced painful choices in trying to earn a living: turn down jobs that demanded they forgo yarmulkes and remain beyond sunset on the eve of Sabbath or resign themselves to flouting their religious traditions. That began to change sharply in the 1960s because of activists like Mr. Schick.

In 1965 he founded the National Jewish Commission on Law and Public Affairs, known as COLPA, which successfully brought lawsuits and sought new legislation. And as a liaison to the Jewish community for Mayor John V. Lindsay of New York, he carved out other accommodations for the Orthodox. In the wake of such ferment, American society and law became more sensitive to the sometimes arcane needs of the Orthodox.

Municipal hospitals and jails offered kosher food. Government agencies and public utilities paved the way for Orthodox communities to set up eruvim — demarcated boundaries between which Orthodox followers were allowed to carry small items like keys and push baby carriages on the Sabbath. Orthodox Jews in the military were allowed to retain their yarmulkes and beards. And after a lawsuit brought by COLPA, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company agreed to accommodate the schedules of those who observed the Sabbath.

While Mr. Schick worked for the city, the Lindsay administration even arranged for Hasidic families in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, to be given priority for apartments on the lower three floors of public housing so that they would not have to press elevator buttons on the Sabbath.

Perhaps most important, as a result of legal battles brought by COLPA and Roman Catholic organizations as well, government was allowed to provide aid to yeshivas and day schools in a few discrete categories — like transportation, textbooks and computers — after the courts ruled that such help did not violate the constitutional prohibition against the establishment of religion.

“In the 1950s, people thought we were residual and we were going to die out,” said Samuel Heilman, a distinguished professor of sociology at the City University of New York and the author of several books on the Orthodox world. “People like Schick came along and said America is a free country and allows people to practice as they see fit.”

Mr. Schick, who was an ordained rabbi and had a doctorate in political science, taught political science and constitutional law at Hunter and Lehman Colleges and the New School for many years. He wrote a book on the American judge and judicial philosopher Learned Hand (1872-1961), “Learned Hand’s Court” (1970).

For over 40 years, Mr. Schick was the unpaid president of Rabbi Jacob Joseph School, one of the nation’s oldest and most prestigious yeshivas, whose alumni include Sheldon Silver, the former speaker of the New York State Assembly, and Robert Aumann, who won the 2005 Nobel in economic science. Mr. Schick helped rejuvenate the school and transplanted it from its dilapidated home among the tenements of the Lower East Side to two campuses on Staten Island and one in Edison, N.J.

Mr. Schick was born in Manhattan on July 3, 1934, 15 minutes ahead of his twin brother, Allen, who was born after midnight on July 4. Their father, Joseph, an immigrant from Romania, was the rabbi of the West Side Jewish Center on West 34th Street. He died when the twins were 4. With no close relatives in New York and facing eviction, Mr. Schick’s mother, Renee Schick, placed Marvin and Allen in an orphanage while she and her two other children moved to a small apartment in Borough Park, Brooklyn.

At the urging of a European relative, she baked challahs in her home oven before the Sabbath and sold them to earn a living. They sold so well that she was able to reunite the family by 1943 and open a kosher bakery, Schick’s, which became one of Brooklyn’s most popular. The family lived above the bakery.

Marvin studied at Rabbi Jacob Joseph, remaining beyond high school to complete rabbinical ordination while he also attended Brooklyn College. After graduation, he pursued his doctorate at New York University, where at one point its president, James Hester, was looking for an assistant. Two professors recommended Mr. Schick.

“The problem was that I wore a yarmulke,” Mr. Schick later wrote in an article, “and Hester would not have any of that. I did not get the job.”

Such incidents motivated him in the mid-1960s to discuss strategies with Moshe Sherer, who at the time was president of Agudath Israel of America, the umbrella group for haredi Jews — Hasidim and Orthodox Jews who adhere to a rigorous tradition of Talmud study that originated in Lithuania and are sometimes known as “Yeshiva world” Jews. Mr. Schick soon founded COLPA to represent Orthodox Jews more aggressively than mainstream Jewish organizations were doing.

“We were advocates, even fighters, and we weren’t afraid to be militant or unpopular,” he wrote.

In numerous articles in Jewish newspapers and in speeches, Mr. Schick assailed banks, insurers and utilities as well as city officials for tolerating discrimination against Sabbath observers. Sid Davidoff, then a key aide to Mayor Lindsay, recruited him to be an assistant for intergroup relations, deciding it was preferable to have him stirring matters up inside the mayor’s office than attacking it from outside.

When Mr. Davidoff was dispatched to assess Mr. Lindsay’s 1972 presidential prospects, Mr. Schick was named Mr. Lindsay’s administrative assistant. He soon found himself tangled in a conflict between black and Jewish groups — the dispute over erecting public housing in a middle-class area of Forest Hills, Queens. It was ultimately resolved by a compromise worked out by a Queens lawyer, Mario M. Cuomo, who went on to become governor of New York State.

In addition to his son Avi, who was deputy attorney general of New York State under Eliot Spitzer, Mr. Schick is survived by his brother Allen, an emeritus professor of political science at the University of Maryland; his wife, Malka (Korn) Schick, a 12th-grade English teacher; his daughters Shani Schick, a special-education teacher, and Adina Schick, a professor of applied psychology; another son, Yosef, a lawyer; and eight grandchildren.

For many years, with financing by the Avi Chai Foundation, Mr. Schick took a painstaking census of the nation’s Jewish day schools and yeshivas. In the 2008-2009 school year, he counted 228,174 students in Jewish elementary and secondary schools, a 25 percent increase over a decade. Most of that growth was in Hasidic and Yeshiva-world schools, which, Mr. Heilman said, heartened Mr. Schick because it testified to the stunning success of the Orthodox.

“He was a defender of the faith,” Mr. Heilman said, “and the faith for him was orthodoxy.”