While a common perception is that women are physically unfit for hard manual labour, the truth is that women can carry burdens that men could never take on. This was the viewpoint of Sir Fazle Hasan Abed; everyone’s beloved Abed bhai. We were travelling to Habiganj and he was talking about his experiences from 1974: “No one considered women as an important part of the society. I visited Roumari and found out that the male members of the community had abandoned their families. The women were struggling to survive amidst the famine with their malnourished children. Whatever food they could gather, they would feed it to their children. So, it was not the men but the women who took up responsibility in times of crisis. They keep struggling till the end to get out of danger. The lesson I learned was that when women are given the right opportunity, they can turn the impossible into the possible.”

By nature, Abed bhai was a reticent person. If you asked him anything, rarely would he answer in detail. One had to ask him something repeatedly to get a concrete answer. But when it came to the struggles of women, he needed little prodding to continue. “Society prevents women from getting things done. It creates many impediments for them,” Abed bhai was always reiterating. During that period, poultry and livestock diseases were very common. Farmers often lost their cows to diseases, too. Usually, such misfortune would also mean that the poor farmer lost all his possessions.

A group of boys and girls were trained for three months to become veterinary workers. In Abed bhai’s words, “Someone commented that girls won’t be able to give injections to the cows,” said Abed bhai. “But the girls did a better job than the boys. Still, the refrain of ‘girls can’t do it’ didn’t stop. After the first batch, I stopped taking in boys; all the subsequent para veterinary workers were girls.”

This was the story Abed bhai liked to tell anyone who said girls could not do something or the other.

“Bangladeshi girls can do everything. They carry a pail full of water and a child at the same time. They climb up steep land effortlessly. There is no work that girls can’t do. Such thoughts only prove the limitation of the male mindset.”

At the time, the child mortality rate was extremely high in Bangladesh. Tetanus itself would cause the death of seven percent of infants every year. A shot of tetanus toxoid could prevent this, so Abed bhai decided to focus on providing this life-saving vaccine to children. Collecting vaccines and training people on how to give injections was the easy part. But the vaccines needed to be stored in freezing conditions, and so refrigerators had to be arranged at thana levels. Temperature control was also required while taking them to the villages. When BRAC was running a chicken vaccination project, they faced the same problems. However, the situation was dealt with by carrying the vaccines inside ripe bananas, which kept them cool.

A vaccine project for children of massive scale, however, was impossible for BRAC to go ahead with without the government’s support. Abed went to see the then president Ziaur Rahman, who was duly impressed. However, the practical problem was that all thanas still didn’t have access to electricity. The then president assured him, “I have set up the Rural Electrification Board. Within five years, all thanas will get electricity. But now you should think about something else. The vaccine initiative will need a few years to reach fruition.”

Abed started thinking and determined that the main culprit behind child mortality was diarrhoea. In 1968, the then South-East Asia Treaty Organisation Cholera Research Laboratory (now icddr,b) had come up with the oral saline formula consisting of salt, glucose, and potassium. However, it could not be taken to the people. BRAC started collaborating with icddr,b and a huge workforce was trained to popularise saline.

Abed bhai told us, “Our workers have reached each and every village household. Men, women, imams from mosques, and village matobbors were made to understand and learn the saline making process. We used to mark rice cooking pots to show them how to measure half a litre of water. We had to do so many experiments. We realised that poor people perceived saline to only be for them, not for the rich. So we started advertising on TV and their perception started changing.”

After its success in Bangladesh, Indonesia and several countries from Africa took help from BRAC and started their own oral saline initiatives with success.

BRAC was founded in response to the aftermath of the Liberation War. Abed bhai once said, “I went to England for higher studies before the war, and I had specific plans. However, after the war, only the betterment of the country and people occupied my mind. Even though I was in the UK during the war, I still worked to liberate Bangladesh. As a continuation of that effort, it was inevitable that I’d return and establish BRAC. Marietta was my girlfriend then, and we were supposed to get married. But she refused to go to Bangladesh, and I refused to stay back in the UK. At that point in time, there was only Bangladesh in my thoughts. Marietta significantly contributed towards the war, too. However, I chose my country over her.”

After the Liberation War ended, Abed bhai was frustrated about the way the country was being led. He said, “We did not learn the lesson that we were supposed to learn from the Muktijuddho. Bangabandhu’s Awami League is in power. It’s a war-torn nation and it’s chaotic everywhere. But there are no efforts to transform and build Bangladesh as a model nation.”

Abed bhai held high opinions about Tajuddin Ahmad: “If Tajuddin was not cast aside and was instead given more opportunities, Bangladesh’s history could have been different. Tajuddin had unmatched education, honesty, and leadership capabilities.”

Abed bhai defined a great and worthy leader as someone who always steps down to accommodate a worthier leader, saying, “Nelson Mandela could have stayed in power for 10 more years if he wanted to, but instead he paved the way for the future [worthy leadership] by stepping down.”

About his achievements, Abed bhai was very self-effacing: “Maybe people think I am a successful person. I established the world’s largest NGO and I’ve received many awards and prizes. However, I did not work for awards. I am satisfied with my work because I’ve worked for the people, the poor, and for those who are not in everyone’s thoughts. But I am not complacent. Still a lot of work is left to be done.”

BRAC is continuing his “remaining work,” both at national and international levels. We lost Abed bhai to a life-threatening disease on December 20, 2019. Had he survived, we would have celebrated his 88th birthday on April 27 of this year.

Translated from Bangla by Mohammed Ishtiaque Khan

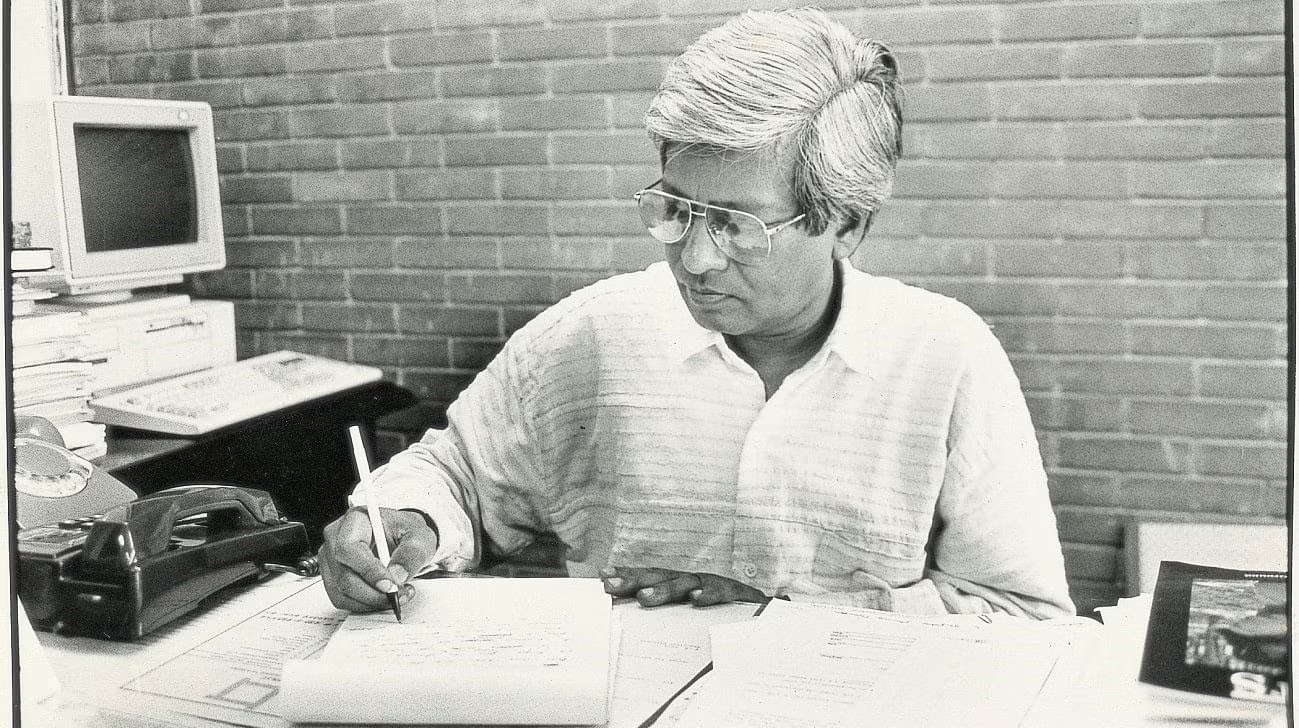

Golam Mortoza is editor of The Daily Star Bangla and author of ‘Fazle Hasan Abed o BRAC’ (Mowla Brothers, 2006).