A four-part exhibition premiering this fall showcases the contemporary artist’s multimedia portrayals of Black femininity

Museums are rife with images of nude white women reclining on chaise lounges. Take Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538): The titular figure lies naked atop a wrinkled white sheet, offering viewers a sidelong glance and a slight smirk. Her left hand hides her crotch, while her right hovers above a bundle of roses. Another famous nude, Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863), shows a model lounging on a couch while her Black servant brings her a bouquet of multicolored flowers.

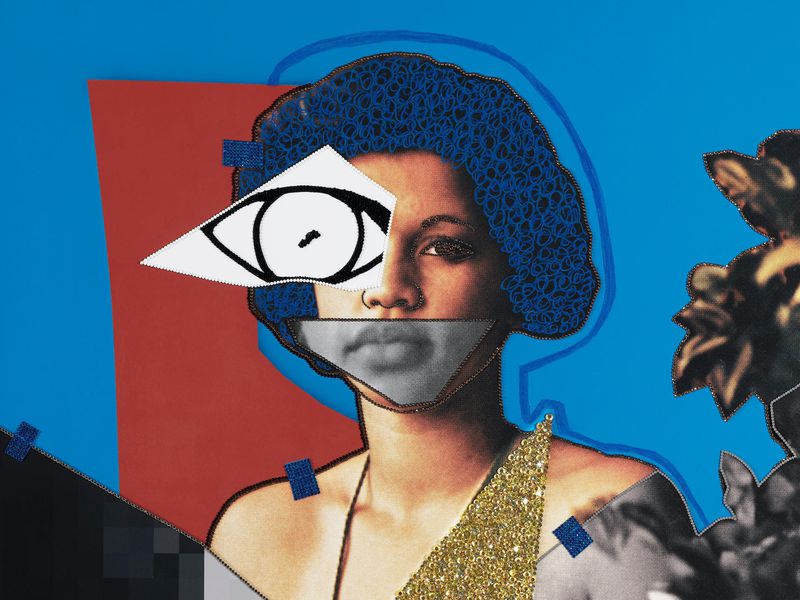

Mickalene Thomas, a contemporary African American artist known for her stunning collages, is attempting to challenge these passive, racialized depictions by “portraying real women with their own unique history, beauty and background,” as she told Smithsonian magazine’s Tiffany Y. Ates in 2018. One of the artist’s recent collages, Jet Blue #25 (2021), epitomizes this philosophy: The piece uses blue acrylic paint, glimmering rhinestones and chalk pastel to create a fragmented image of a Black woman who meets the spectator’s gaze instead of avoiding it.

According to Vogue’s Dodie Kazanjian, the portrait is part of Thomas’ Jet Blue series, a compilation of collages that appropriates images from pinup calendars published by the Black-centric Jet magazine between 1971 and 1977.

“What I’m doing is reimagining Jet’s representation of African American women as objects of desire by composing the figures within ornamental tableaux to exhibit Black female empowerment,” Thomas tells Vogue.

Jet Blue #25 and other works from Thomas’ oeuvre will be featured in the artist’s latest exhibition, “Beyond the Pleasure Principle.” Per a statement, the four-part presentation will consist of a “series of related, overlapping chapters” at Lévy Gorvy’s New York City, London, Paris and Hong Kong locations. Paintings, installations and video works on view will explore the Black female body “as a realm of power, eroticism, agency and inspiration.”

“I’ve known Mickalene her entire career,” gallery co-founder Dominique Lévy tells Artnet News’ Eileen Kinsella. “I felt that if she had the time, the space and the creative energy it would be extraordinary to have an exhibition that unfolded in four parts. Wherever you are in our four galleries you can see physical works, and you can still experience the full exhibition online. To me this is really the world of tomorrow.”

As Culture Type’s Victoria L. Valentine reports, the show is set to launch ahead of the release of the artist’s first comprehensive monograph, which will be published in November by Phaidon. The fully illustrated tome features the artist’s paintings, collages, photographs, videos and installations alongside commentary by art historian Kellie Jones and writer Roxane Gay.

One highlight of the exhibition, Resist (2017), is a collage of images from the civil rights movement: police officers attacking future congressman John Lewis near the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma in 1965, portraits of Black luminaries like James Baldwin and scenes of protest.

“Mickalene is more than an artist,” Christopher Bedford, director of the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA), wherea two-story installation by Thomas is currently on view, tells Vogue. “She’s an activist, a commercial photographer, a designer, an agitator, an organizer, a curator, a public figure and a writer. … In her conception, being an artist today is not one thing but all of those things.”

Born in Camden, New Jersey, in 1971, Thomas had a fraught relationship with her family. As Karen Rosenberg wrote for the New York Times in 2012, both of the artist’s parents were drug addicts; Thomas left home as a teenager, moving to Portland to escape the situation.

“I didn’t want to be in that environment, and I was [also] dealing with coming out,” Thomas told the Times. (She’s now engaged to curator and art collector Racquel Chevremont.)

While visiting the Portland Art Museum, the young artist came across Carrie Mae Weems’ Mirror, Mirror (1987–88), a photograph of a Black woman looking at her reflection and talking to a fairy godmother.

“It spoke to me,” Thomas tells Vogue. “It’s so familiar to what I know of my life and my family. I’m that person. I know that person. It was saying, ‘This is your life.’”

Thomas’ work had been largely abstract at Pratt, but it became far more personal and representational after she took a photography class with David Hilliard at Yale.

During the course, Thomas turned the lens on her mother, Sandra Bush. Eventually, she created a series of collages, paintings and videos of Bush that culminated in the short film Happy Birthday to a Beautiful Woman. The work premiered two months before Bush’s death in 2012.

Most of Thomas’ more recent works, including the artist’s 2014 series Tête de Femme(also on view in “Beyond the Pleasure Principle”), play with motifs of Black womanhood through an “interplay of line, form and material, punctuated with an increased use of color,” per a statement from New York gallery Lehmann Maupin. One painting from the series, Carla (2014), shows a woman made of aqua and chartreuse shapes. The result is a stripped down, more conceptual depiction of the female body.

“What’s happening in art and history right now is the validation and agency of the black female body,” Thomas told Smithsonian magazine in 2018. “We do not need permission to be present.”

“Beyond the Pleasure Principle” opens at Lévy Gorvy in New York City on September 9. Versions of the show will debut at Lévy Gorvy’s London, Paris and Hong Kong locations on September 30, October 7 and October 15, respectively.