When Kirsten Delegard’s grandparents bought their first house in south Minneapolis in 1941, they signed the property’s deed, as is standard for any homebuyer.

But the deed came with this line: “No person or persons other than of the Caucasian race shall be permitted to occupy said premises or any part thereof.”

That language, known as a “racial covenant,” barred any nonwhite resident from buying or living in the property. Such covenants were attached to tens of thousands of homes across Minneapolis, carving inequity directly into the city’s map and creating a foundation for one of the biggest racial wealth gaps of any major American city.

In January, months before George Floyd’s killing thrust racial inequity into the spotlight, Minneapolis enacted an ambitious plan in an attempt to address it. It changed land zoning citywide, acknowledging that the history of covenants created housing inequities that persist to this day.

Minneapolis eliminated single-family zoning, becoming the first major American city to do so. The goal of the new zoning plan, known as Minneapolis 2040, is to create denser housing near transit and jobs, improving the supply and helping combat climate change.

Still, to make the plan a reality, community groups say the city will have to make unprecedented new commitments to affordable housing. As the city seeks to rebuild trust with communities of color, they say housing equity and environmental justice are central, given how entrenched the disparities are.

“Housing is the foundation to everything,” says Shannon Smith Jones, executive director of Hope Community, a Minneapolis housing and community group. “I think communities and housing and all of that needs to be hyper-focused on.”

Discrimination on the map

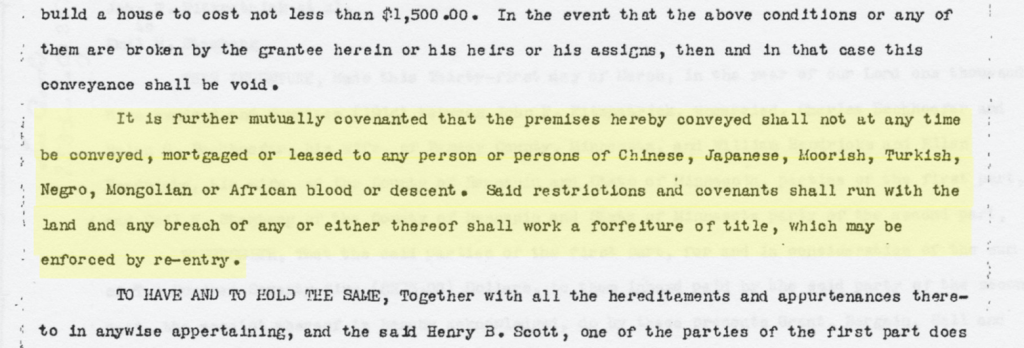

The long legacy of racial covenants became starkly visible in Minneapolis when Delegard and her colleagues created the Mapping Prejudice project at the University of Minnesota libraries. After Hennepin County digitized its collection of property deeds, they began combing through thousands of them in 2016 with the help of volunteers, searching for covenants.

Can’t see this visual? Click here.

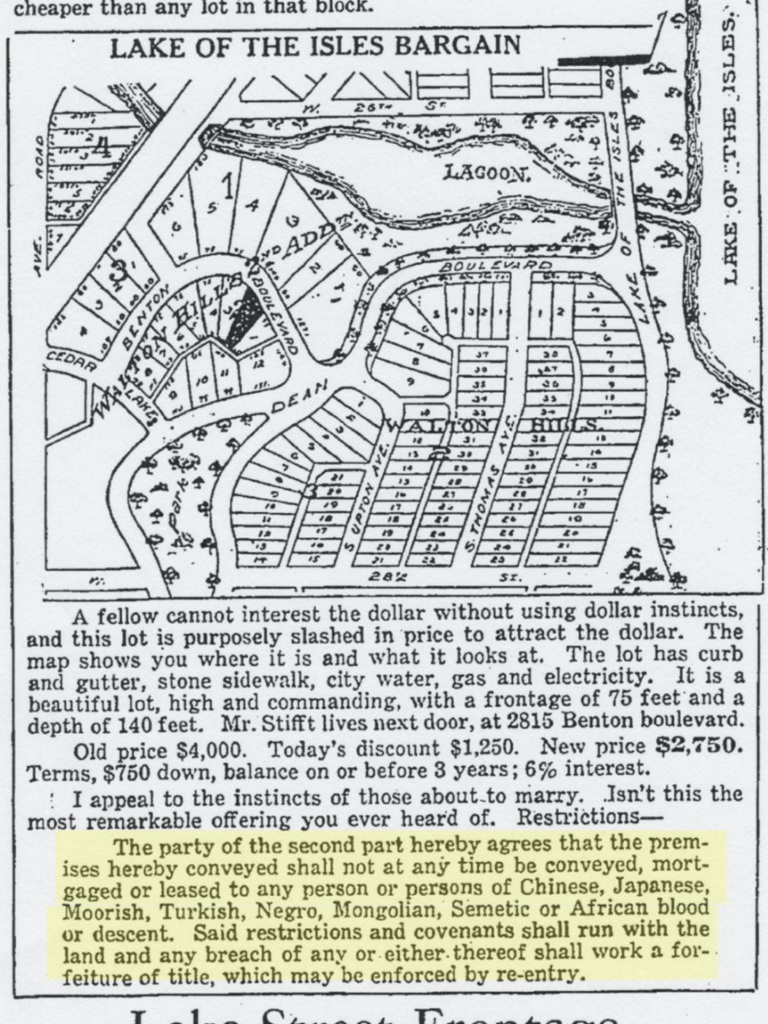

The first were used by land developers beginning in 1910, as Minneapolis was expanding.

“It becomes absolutely standard operating practice, when a new piece of land is divided into lots, to insert these restrictions to make sure that land is reserved for the exclusive use of white people in perpetuity,” Delegard says. “Developers would put them in the real estate ads as one of the selling points of the property.”

The effects were visible in just a few decades. African American residents, who had been living across Minneapolis, were displaced and moved into fewer and fewer neighborhoods.

Banks then “redlined” those neighborhoods, making it difficult or impossible for residents to get a mortgage to buy a home there. City and state planners bisected the areas with freeways as the interstate highway system was constructed in the 1950s and ’60s.

Can’t see this visual? Click here.

Minnesota banned racial covenants in 1953, but as Delegard and her colleagues uncovered, their legacy is still written on the landscape.

“What we found when we started mapping is that covenants created demographic patterns that have remained just completely unmoved,” she says. “So the areas with covenants in them are the richest and whitest parts of the city today.”

Houses that once had racial covenants are worth 15% more on average than identical houses without covenants in Minneapolis, she says. White residents are also three times more likely to own their homes than black residents. Delegard says it shows how a structural wealth gap, created more than a century ago, has endured for generations.

“We have to know our history if we’re going to find any way out of this,” Delegard says. “It can’t be something that people relegate and say, ‘That’s in the past it has nothing to do with me.'”

Delegard and her team shared their work with Minneapolis city officials, just as the city was undertaking a major project on city zoning, dubbed Minneapolis 2040. And they noticed that not long after racial covenants were banned, the city instituted new zoning rules that restricted those neighborhoods to having only single-family homes. That kept the land development pattern locked in for decades.

“A very compelling picture started to emerge about how Minneapolis grew between about 1900 and 2000 in terms of being a very heavily racially segregated city but also being a very intentionally segregated city,” says Heather Worthington, who helped develop the Minneapolis 2040 plan as the city’s director of long-range planning, but is now a private consultant.

Environmental justice ties

Minneapolis also began to consider another central goal for redoing its zoning: combating climate change. Land use patterns can have profound effects on the carbon emissions a city produces.

A lack of affordable housing in cities often pushes residents into the outskirts and suburbs, driving up car use. Many neighborhoods were not designed to promote walking or biking, with jobs, stores and housing in close proximity to each other. The buildings themselves also play a big role in energy efficiency.

“If you live in substandard housing with poor insulation, just by virtue of that fact, you are paying more for your energy bills,” says Sam Grant, executive director of MN350, an environmental advocacy group. “It’s costing you more in the summer when it’s hot and more in the winter when it’s cold.”

As the city drafted its plan, the staff acknowledged that the two central goals, addressing racial inequity and climate change, were intertwined.

“Climate change has a disparate impact on people of color, which is not surprising because they live in areas of cities that have typically suffered from a lack of investment,” says Worthington.

So, the city proposed this: eliminate single-family zoning. In vast swaths of the city, lots would now be allowed to have up to three units, instead of one. Housing could be even denser along major roads, near public transit and near job-rich areas.

Can’t see this visual? Click here.

The plan sparked a communitywide debate, pitting NIMBYs against YIMBYs. Across the city, yards were dotted with dueling lawn signs such as “don’t bulldoze our neighborhoods” or “neighbors for more neighbors.”

In the end, the plan was overwhelmingly passed by the city council.

“These patterns are so durable and were put in place so long ago that cities struggle with how to start to change that fabric,” Worthington says. “Now the city of Minneapolis can make those changes.”

Challenges ahead

Minneapolis’s plan opened the door for other cities and states to take on single-family zoning. Oregon soon followed suit, passing a plan that “upzoned” single-family neighborhoods to duplexes or fourplexes. California lawmakers made a similar attempt, but so far have failed three times to pass legislation.

In Minneapolis’ communities of color, the reaction was more mixed.

“There was a lot of, really, what we saw being self-congratulatory press both locally and nationally,” says Owen Duckworth, director of policy and organizing at the Alliance, a racial justice and housing coalition in the Twin Cities. “And I think that was also quite frustrating.”

Zoning plans are essentially just blueprints for a city. Duckworth says changes on the ground will take new commitments from Minneapolis city leaders, especially to ensure that new housing includes affordable housing. Otherwise, the plan puts lower-income neighborhoods at risk.

“No one is going to come in, buy up a million dollar home in southwest Minneapolis, tear it down and put a fourplex up,” says Duckworth. “Where that sort of phenomenon of property purchasing and displacement is, it’s in lower-income, historically disinvested communities where people are beginning to now feel gentrification and displacement pressures.”

Duckworth says the city recently passed new renter protections, but bigger commitments are needed, like higher funding for affordable housing that spans multiple years, so the market has more predictability. Minneapolis is adding residents, but the city has lost roughly 15,000 affordable housing units since 2000 and rentals are becoming increasingly unaffordable for communities of color.

Unless the city expedites affordable housing, the pace of change is expected to be slow. Since the new zoning rules went into effect, only a handful of new developments were approved prior to the pandemic outbreak.

“It still always feels a little short of where you’re trying to go,” says Smith Jones. “I think by just changing the zoning, you’re missing the intentionality that you need to have to make sure it’s impacting the people you want it to work for.”

Preparing for the effects of climate change also goes beyond housing policy. The more concrete a neighborhood has, the hotter it gets in the summer, especially in a warming climate. Because of this “urban heat island” effect, some neighborhoods that are home to Minneapolis’ black communities can be 10 degrees hotter than other neighborhoods.

“If you looked historically, you would see the restrictive covenants along those green spaces,” Smith Jones says. “So historically we haven’t had the ability to live in very beautiful, nice green spaces that are healthy.”

Though she no longer works for the city, Worthington is hopeful that the new zoning plan will be a foundation for bigger changes to come.

“We’re not now blind to these issues,” Worthington says. “I think the challenge for us will be that we’ll really have to sustain effort and make difficult decisions. We’re a very wealthy area in terms of area median income, but we have not done a great job in thinking about priorities.”

Smith Jones says there is no moving forward in Minneapolis without addressing its systemic inequity, which is part of the city’s makeup. Still, she’s hopeful and plans to make sure that the voices of disadvantaged communities are centered in the city’s rebuilding effort.

“Hope is the thing that gets you up every day,” Smith Jones says. “I believe in the good of people. I believe their hearts. I know we definitely have bad apples out there, but I think that if we all really dig in deep and tap into that, that collectively we can have a big impact.”

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit NPR.