Minority Mental Health workshop highlights need for BIPOC representation in therapy

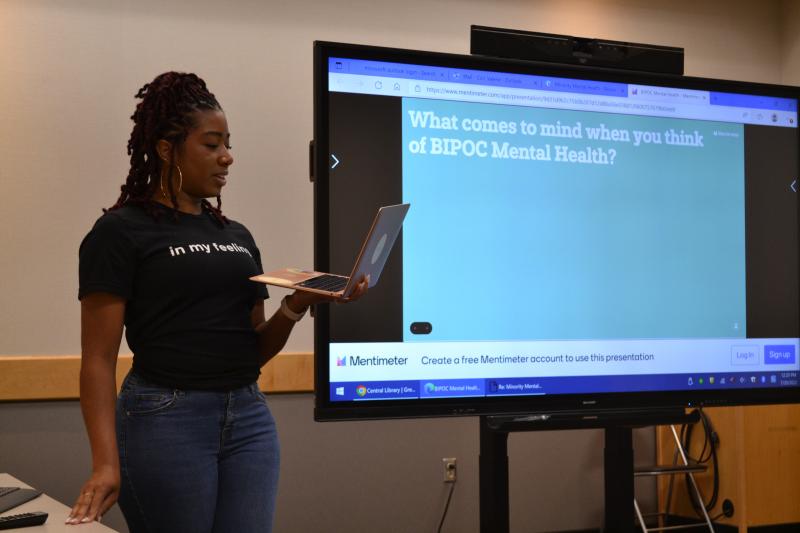

Greensboro-area licensed therapist Nicole Osborne led a minority mental health workshop in a black t-shirt with the phrase, “In my feelings.”

It made sense. Osborne said her goal for the event was to break the stigma around talking about your emotions and seeking help for mental health issues.

The free workshop on July 20 was the second in the “Diving into Diagnosis” series put on by the Greensboro Public Library in partnership with the Kellin Foundation.

For an hour and a half, Osborne, a Black woman herself, spoke about the mental health challenges specific to BIPOC individuals and resources for care.

She started with some reasons why people of color might be depressed, anxious, and/or traumatized.

“The first one is being strong. And so I know in some communities and cultures, being strong is everything and so for you to show weakness is a bad thing,” she said. “You get talked about. People call you crazy if you show emotions.”

When Osborne talked about the stereotype of the “strong Black woman,” the handful of attendees — mostly Black women — nodded and groaned knowingly.

“Doing everything on your own, not asking for help, that leads to burnout very, very quickly,” she said. “And that leads to an array of mental health issues.”

She also named family and social pressures, racism and discrimination, code-switching, and people-pleasing as other factors causing mental health issues.

“If you speak a certain language at home, but you don’t speak it with other people, that can get really tiring and exhausting for you mentally,” Osborne said. “Also, for myself personally, being from the Black community, feeling like I have to show up a certain way in white spaces.”

With so many root causes of mental health issues related to race and culture, Osborne said it was crucial for therapists to demonstrate cultural competency with their clients.

She gave the example of a Black woman who was pulled over by the police for speeding. For that woman, it was a traumatic event. But she said a white therapist, or a therapist without cultural competency, might not understand why.

“If you don’t understand the history, and the police brutality and the police violence, you’re going to miss that and not understand how traumatic that is,” Osborne said.

That issue is just one example she gave as to why BIPOC representation in therapists is important.

Currently, that representation is lacking.

According to the American Psychological Association, in 2020 nearly 85% of psychologists in the country were white.

Osborne said that if people seeking therapy went online in search of a therapist, they were likely to find pages and pages of white therapists.

“There’s nothing wrong with that, but if you scroll and you filter, I want a Mexican therapist or I want an Asian therapist, you’re going to see maybe two pages of stuff, as opposed to white therapists, you’re going to see 20,” she said.

Though Osborne started her own practice, Milk & Honey Therapy, she originally set out to be a school counselor.

She said she often saw one school counselor for hundreds of students and identified the need for more mental health support in schools as well as BIPOC representation.

“Even doing small things like having the posters you choose be BIPOC-represented or the books that you choose, or the activities that you create. … Those things can go a long way for a child just to be able to see those things on a daily basis to be like, okay, my culture matters, my representation matters,” Osborne said.

She also spoke about the need for teachers to have trauma-informed training. Her husband, also a therapist, worked a lot with younger children in the school system who were diagnosed with Oppositional Defiant Disorder.

“They’re like, ‘Oh, that kid is bad. That kid has anger issues,’ but it’s like, but why does he have these issues? Nobody’s asking those questions,” Osborne said. “So people … misdiagnose them with ODD when in reality, it’s PTSD, or it’s trauma.”

Another issue Osborne said she’d seen with youth was resistance from the parents with regards to therapy.

She said she had a teen client whose parents stopped her therapy after a month because they didn’t agree with it.

For youth in similar situations, Osborne gave tips for self-help including getting enough sleep, eating three meals a day, staying hydrated, and cutting down on screen time. Some of her younger clients say they spend eight hours or more on their phones (especially on TikTok) a day.

Though she advocates for less time on the phone, Osborne said there were some valuable mental health resources available on the internet for people looking for self-help.

“YouTube has meditation, it has yoga, stretching. They also have just therapists who actually talk about psychoeducation and different things that you can do,” she said. “And so you can get a lot of information from there.”

She also recommended books like “The Unapologetic Guide to Black Mental Health,” podcasts like Therapy for Black Girls and Latinx Therapy, and meditation apps specifically designed for BIPOC individuals like the Shine App.

The library’s mental health series will continue on Aug. 31 from 12 p.m. to 1:30 p.m. with a workshop about managing stress and anxiety.

Amy Diaz covers education for WFDD in partnership with Report For America. You can follow her on Twitter at @amydiaze.

Amy Diaz covers education for WFDD in partnership with Report For America. You can follow her on Twitter at @amydiaze.