Actor Chadwick Boseman’s death from colon cancer in 2020 brought attention to the trend

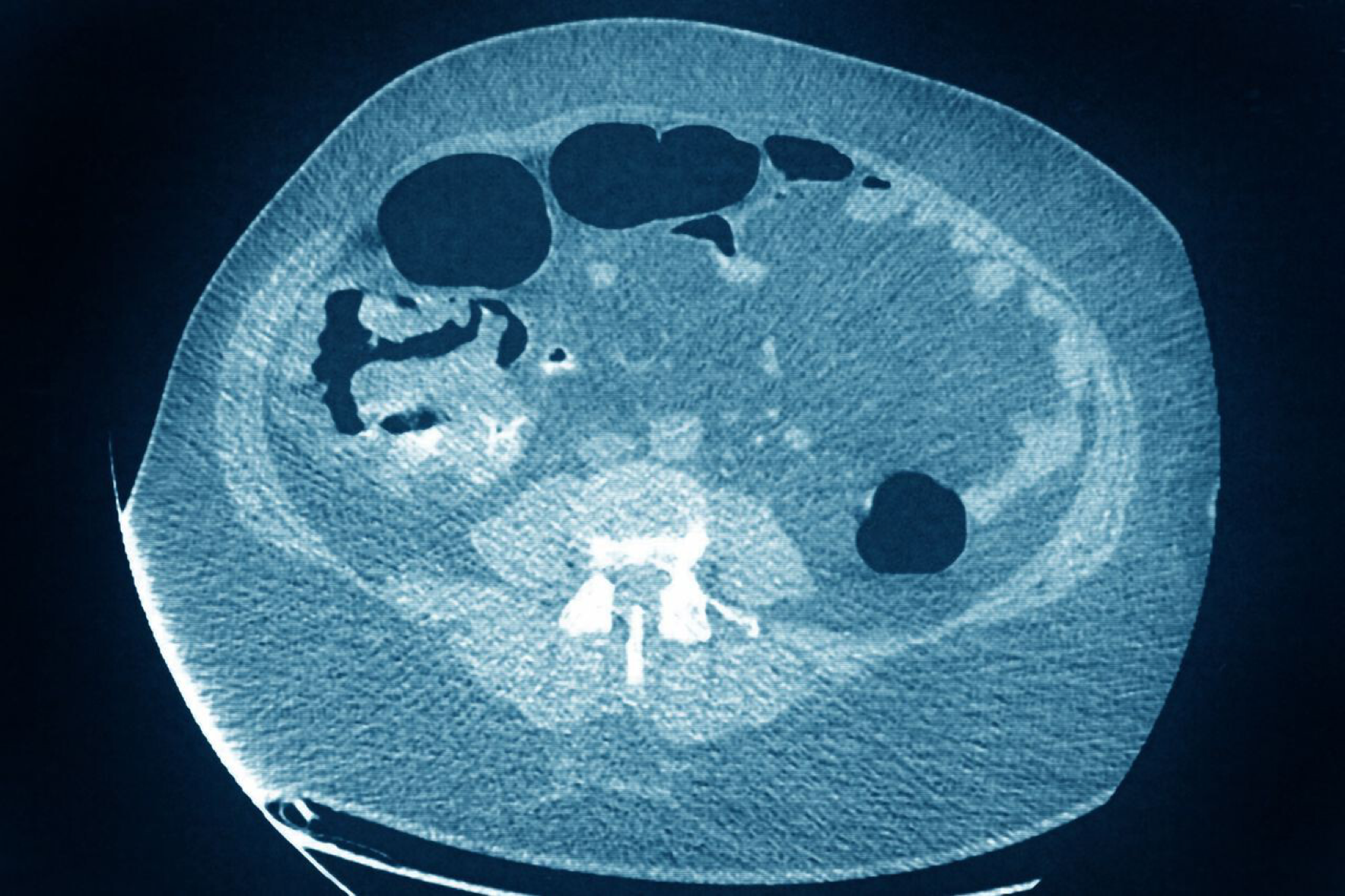

A larger share of people are being diagnosed with colorectal cancer at a younger age and at a more dangerous stage of the disease, a report showed. Doctors aren’t sure why.

The American Cancer Society said Wednesday that about 20% of new colorectal cancer diagnoses were in patients under 55 in 2019, compared with 11% in 1995. Some 60% of new colorectal cancers in 2019 were diagnosed at advanced stages, the research and advocacy group said, compared with 52% in the mid-2000s and 57% in 1995, before screening was widespread.

Cases and death rates for colorectal cancer have continued a decadeslong decline overall thanks to screening, better treatments and reductions in risk factors such as smoking, the ACS report’s authors said. But the shift of the burden toward younger people and diagnoses at more advanced stages has oncologists on alert.

“The improvements have slowed, and they’ve slowed because of this opposite trend we’re seeing in young people,” said Kimmie Ng, director of the Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer Center at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. “More and more are getting diagnosed with cancer that might not be curable.”

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancer types in the U.S. and the second-deadliest behind lung cancer. Some 153,000 diagnoses are expected in 2023, ACS estimated, including some 19,500 cases in people under 50. The cancer is most common among people 65 to 74, but the case rate among people under 50 has risen quickly. Actor Chadwick Boseman’s death in 2020 from colon cancer at age 43 drew more attention to the trend.

Researchers aren’t sure why rates among younger people are increasing. Changes in known risk factors including unhealthy diets, alcohol consumption and physical inactivity could contribute but don’t fully explain the trend, oncologists said. Some think environmental changes could be reshaping the makeup of microorganisms in people’s bodies, called the microbiome, putting them at risk.

“I see so many young patients who live really healthy lifestyles that get diagnosed with metastatic colon cancer,” said Dr. Ng. “There are other environmental exposures that need to be looked at.”

Drivers of the shift toward later-stage diagnoses also aren’t clear, doctors said, but plateauing screening rates likely contribute. Younger patients also tend to be diagnosed at later stages, in part because doctors can mistake symptoms such as abdominal pain, blood in the stool and unintended weight loss for something else in those age cohorts.

The ACS and a panel backed by the U.S. government in recent years have lowered their recommended threshold for screening to 45 from 50 in light of the trends.

Justin Kelly, 46, said he didn’t realize he was eligible for screening until it came up during a physical last spring. He didn’t have any symptoms and saw himself as low-risk. His stool-based screening test came back positive and a colonoscopy revealed that he had stage-three cancer. He is receiving treatment at Dana-Farber.

Mr. Kelly learned after his diagnosis that he had Lynch Syndrome, a genetic condition that increases the risk of some cancers. He said a doctor told him that if he hadn’t come and his tumor hadn’t been detected, he likely wouldn’t have lived to 50.

“It’s pretty jarring when you hear something like that,” said Mr. Kelly, who works for a medical-device company and lives in Portsmouth, N.H. “I have a lot of friends who have rushed to schedule their colonoscopies after hearing my news.”

About 43% of diagnoses under age 50 are in people 45 to 49, the ACS said in its report published in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

“There are a good portion that are still younger than 45,” said Dr. Jordan Kharofa, a radiation oncologist at the University of Cincinnati Cancer Center, who wasn’t involved with the study.

P eople with a family history of colorectal cancer or other risk factors should talk with their health provider before age 45, said ACS Chief Executive Officer Karen Knudsen. There are also screening gaps among people who are eligible, Dr. Knudsen said. Among people 45 to 49, screening uptake is around 20%, the report said. Uptake is also low among people without health insurance.

Alaska Native, American Indian and Black people have higher rates of colorectal cancer incidence and deaths than other groups, and men have higher case rates than women. There are also stark geographic disparities, with higher case and mortality rates in Appalachia and parts of the South and Midwest.

The disparities could reflect differences in risk factors and in access to screening and treatment, oncologists said. Endoscopy services are limited in much of Alaska, for example, ACS said, resulting in lower screening rates and contributing to higher disease burden among Alaska Natives.

Write to Brianna Abbott at brianna.abbott@wsj.com