For all the strides New Jersey’s redistricting commission made in redrawing the state’s legislative map this month, the final product “over-represents white people” and “actively diminishes the voices of communities of color,” according to a group of advocates.

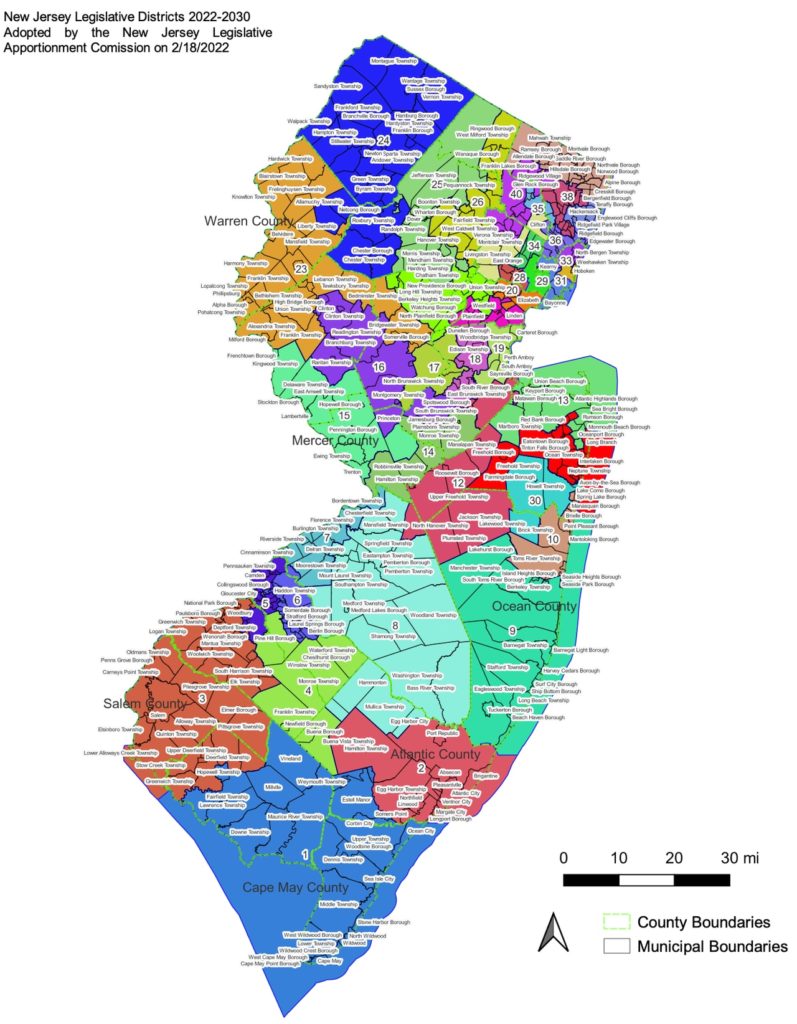

The map released last week splits the state into 40 legislative districts — 17 with a population in which the majority of residents are people of color, and 23 in which the majority of residents are white.

That’s up from the 15 majority-minority districts in New Jersey’s current legislative map.

But Fair Districts New Jersey, a nonpartisan coalition aiming to reform the state’s redistricting process, says that still falls short of the 20 districts the group pressed the commission to adopt.

The organization said while the Garden State is made up of almost 50% people of color as of the 2020 U.S. Census, the map fails to fully account for the growth of Latino, Black, and Asian communities over the last decade.

“Plainly, a map that fails to precisely mirror the population growth of our state fails to truly serve communities of color,” Fair Districts said in a statement.

Every 10 years, a bipartisan commission redraws the lines for the 40 districts representing the state’s 565 municipalities in the state Legislature, the body in Trenton that crafts the state’s laws and passes its budget. Usually, a tie-breaker is needed to pick one party’s map over the other.

But for the first time ever, the commission voted 7-2 to pass a bipartisan compromise last week. The new map takes effect for next year’s elections, when all 120 seats in the Legislature are on the ballot again.

Al Barlas, chairman of the Republican delegation on the commission, cheered the map as one “everyone could be proud of.” LeRoy Jones, chairman of the Democratic delegation, called it “a fair legislative map that is representative of all of New Jersey and the residents it serves.”

Advocates did praise the commission for reaching a bipartisan deal, as well as for releasing early versions of possible maps and holding public hearings where they repeatedly pushed for making the map more reflective of the state’s diversity.

Still, Matthew Duffy, special counsel for redistricting at the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, said the bigger issue is that redistricting is “designed to be a political process” in the first place.

“Bipartisan is not nonpartisan,” Duffy said. “What the parties want is not necessarily great for the residents of New Jersey. … I think we’d love to see a process made it more focused on the people who live here and not the parties.”

Barlas told NJ Advance Media a big goal of the commission was recognizing and embracing the state’s diversity, and the members met with advocates to address their concerns. He also stressed how this map includes two more majority-minority districts than the current map.

“Would we have liked more? Of course,” Barlas said. “But 17 is a significant number. It’s an improvement from where we are today.”

“There’s a delicate balancing act to drawing these lines,” he added.

The new map includes one majority-Black district (Essex County’s 28th) and two majority-Hispanic districts (Hudson County’s 33rd and North Jersey’s 35th).

Meanwhile, there is one Black influence district (North Jersey’s 34th) and three Hispanic influence districts (Union County’s 20th, Essex County’s 29th, and North Jersey’s 36th). Those are districts in which one voting bloc is large enough to influence an election.

But the Fair Districts coalition said that’s still disproportionate because Black communities account for more than 15% of New Jersey’s population and Latino communities represent more than 20% of the state.

Plus, the group said, the Asian community is the state’s fastest-growing demographic, growing by 44% over the last decade, yet the map does not include any Asian plurality districts.

Hudson County’s 32nd District will now be about 30% Asian American.

The two additional districts that will go from having a majority of white residents to to a majority of minority residents under the new map are South Jersey’s 5th and North Jersey’s 27th.

The commission also put a number of previously split diverse communities together in one district:

- Camden and Pennsauken in Camden County.

- Bridgeton, Vineland, Millville, and Fairfield in Cumberland County.

- Dover, Mine Hill, Wharton, and Morristown in Morris County.

That, Fair Districts noted, was in line with what they sought.

But the coalition said a number of diverse communities remain split: West Windsor and Plainsboro; Parsipanny, Millburn, and Livingston; Clifton and Passaic; Wayne and Pompton Lakes; and West Milford, Mahwah, and Ringwood, where the Ramapough-Lenape tribe is based.

“They’re small but they’re really strong communities of interest,” Duffy said.

Members of the redistricting commission also see improvement in the future, with at least three districts — Atlantic County’s 2nd, Central Jersey’s 14th, and North Jersey’s 38th — likely becoming majority-minority districts when the next map is drawn in a decade.

As for the racial makeup of lawmakers themselves? Currently, the Legislature consists of a majority of white men, though there were a number of firsts among the new members sworn in last month.

Democratic Assembly members Sadaf Jaffer, Shama Haider, and Ellen Park are the first Asian American women to hold seats in the Legislature. Haider and Jaffer are also the first two Muslims state lawmakers.

Don Guardian, a former Atlantic City mayor who will now represent South Jersey’s 2nd District in the Assembly, is the first openly gay Republican elected to the Legislature and the state’s first openly gay lawmaker in more than three years.

Meanwhile, Teresa Ruiz, D-Essex, the new Senate majority leader, is the first woman of color to hold that position in state history and the highest-ranking Latina in the Legislature’s history.

The new map could add some more diversity to the Legislature’s ranks. It was redrawn in a way that means at least four powerful Democratic members of the state Senate will be placed across two districts: Richard Codey and Nia Gill in the reshaped 27th, as well as Nicholas Sacco and Brian Stack in the reshaped 33rd.

Sacco announced his retirement on Thursday, avoiding what could have been a nasty Democratic primary between he and Stack.

Codey, a former governor and Senate president, and Gill — who have long been allies — are expected to both run for re-election. Whoever loses their Democratic primary will be bounced from the Legislature.

Democrats, however, likely won’t lose Senate seats because of the move. They’ll simply have two new senators in place of Sacco and whoever loses a Codey-Gill primary. Under the new configuration, both the 34th District in Essex County (which Gill currently represents) and the 32nd District in Hudson County (which Sacco currently represents) will now have open Senate seats that favor Democrats.

Assemblywoman Britnee Timberlake, D-Essex, who is Black, is considered a favorite to run for the Senate in the 34th. If she wins and Gill, who is Black, defeats Codey and then takes the general election, that would put one more Black woman in the Senate. If she wins and Codey, who is white, defeats Gill and then takes the general election, there would be the same number of Black women in the chamber.

Assemblyman Raj Mukherji, D-Hudson, has already announced he will run for Senate in the 32nd, which includes Hoboken and parts of Jersey City. Mukherji could become only the second Asian American member of the Legislature’s upper house.