“Healthy, female workers between the ages of 20 and 40 wanted for a military site,” reads the job advertisement from a 1944 German newspaper. Good wages and free board, accommodation and clothing are promised.

What is not mentioned is that the clothing is an SS uniform. And that the “military site” is Ravensbrück concentration camp for women.

Today the flimsy wooden barracks for the prisoners are long gone. All that remains is an eerily empty, rocky field, about 80km (50 miles) north of Berlin.

But still standing are eight solidly built, attractive villas with wooden shutters and balconies. They are a 1940s Nazi version of medieval German cottages.

That is where the female guards lived, some with their children. From the balconies they could overlook a forest and a pretty lake. “It was the most beautiful time of my life,” said one former female guard, decades later.

But from their bedrooms they would have also seen chain-gangs of prisoners and the chimneys of the gas chamber.

“A lot of visitors coming to the memorial ask about these women. There are not so many questions about men working in this field,” says Andrea Genest, director of the memorial museum at Ravensbrück, as she shows me where the women lived. “People don’t like to think that women can be so cruel.”

Many of the young women came from poorer families, left school early and had few career opportunities.

A job at a concentration camp meant higher wages, comfortable accommodation and financial independence. “It was more attractive than working in a factory,” says Dr Genest.

Many had been indoctrinated early in Nazi youth groups and believed in Hitler’s ideology. “They felt they were supporting society by doing something against its enemies,” she said.

Hell and home comforts

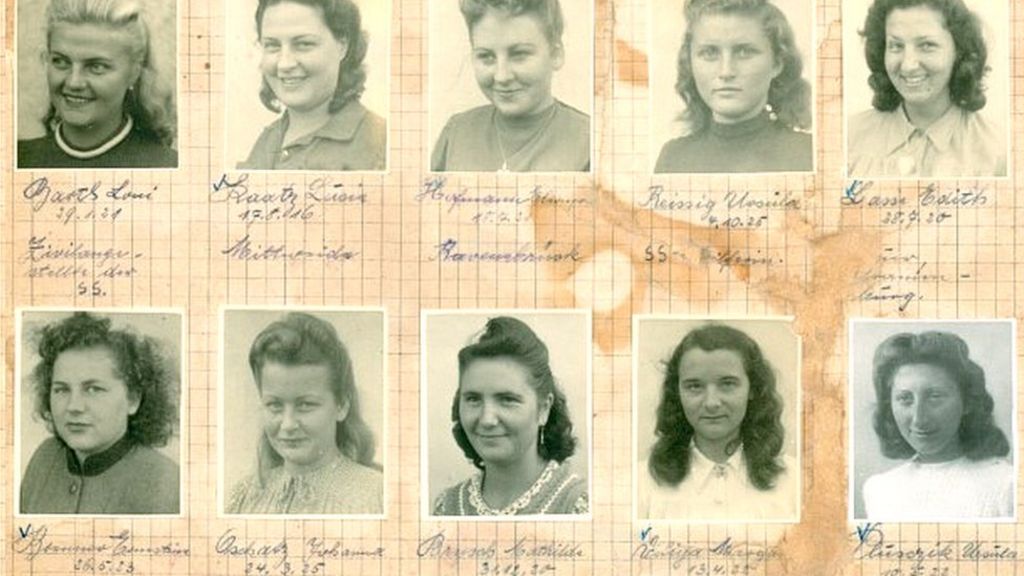

Inside one of the houses a new exhibition displays photos of the women in their spare time. Most were in their twenties, pretty with fashionable hairstyles.

The pictures show them smiling while having coffee and cake at home. Or laughing, arms linked, as they go for walks in the nearby forest with their dogs.

The scenes look innocent – until you notice the SS insignia on the women’s clothes, and you remember that those same Alsatian dogs were used to torment people in the concentration camps.

Some 3,500 women worked as Nazi concentration camp guards, and all of them started out at Ravensbrück. Many later worked in death camps such as Auschwitz-Birkenau or Bergen-Belsen.

“They were awful people,” 98-year-old Selma van de Perre tells me on the phone from her home in London. She was a Dutch Jewish resistance fighter who was imprisoned in Ravensbrück as a political prisoner.

“They liked it probably because it gave them power. It gave them lots of power over the prisoners. Some prisoners were very badly treated. Beaten.”

More on the Holocaust and other Nazi crimes:

In depth: The Holocaust year by year

How Auschwitz became centre of Nazi Holocaust

‘Great lady of the French Resistance’ dies at 103

Former Nazi SS guard found guilty over mass murder

Selma worked underground in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands and bravely helped Jewish families escape. In September she published a book in the UK about her experiences, My Name Is Selma. This year it will be released in other countries, including Germany.

Selma’s parents and teenage sister were killed in the camps, and almost every year she returns to Ravensbrück to take part in events to ensure the crimes committed here are not forgotten.

Ravensbrück was Nazi Germany’s largest female-only camp. More than 120,000 women from all over Europe were imprisoned here. Many were resistance fighters or political opponents. Others were deemed “unfit” for Nazi society: Jews, lesbians, sex workers or homeless women.

At least 30,000 women died here. Some were gassed or hanged, others starved, died of disease or were worked to death.

They were treated brutally by many of the female guards – beaten, tortured or murdered. The prisoners gave them nicknames, such as “bloody Brygyda” or “revolver Anna”.

After the war, during the Nazi war crimes trials in 1945, Irma Grese was dubbed the “beautiful beast” by the press. Young, attractive and blonde, she was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death by hanging.

The cliche of the blonde, sadistic woman in an SS uniform later became a sexualised cult figure in films and comics.

But out of thousands of women who worked as SS guards, only 77 were brought to trial. And very few were actually convicted.

They portrayed themselves as ignorant helpers – easily done in patriarchal post-war West Germany. Most never talked about the past. They got married, changed their names and faded into society.

One woman, Herta Bothe, who was jailed for horrendous acts of violence, did later speak publicly. She was pardoned by the British, after just a few years in prison. In a rare interview, recorded in 1999 just before she died, she remained unrepentant.

“Did I make a mistake? No. The mistake was that it was a concentration camp, but I had to go to it, otherwise I would have been put into it myself. That was my mistake.”

That was an excuse former guards often gave. But it was not true. Records show that some new recruits did leave Ravensbrück as soon as they realised what the job involved. They were allowed to go and did not suffer negative consequences.

I ask Selma if she thinks the guards were diabolical monsters. “I think they were ordinary women doing diabolical things. I think it’s possible with loads of people, even in England. I think that can happen anywhere. It can happen here if it’s allowed.”

It’s a chilling lesson for today, she believes.

Since the war female SS guards have been fictionalised in books and films. The most famous has been The Reader, a German novel that later became a film starring Kate Winslet.

Sometimes the women are portrayed as exploited victims. At other times as sadistic monsters.

The truth is more horrifying. They were not extraordinary monsters, but rather ordinary women, who ended up doing monstrous things.