Equality is about ensuring that every individual regardless of race, religion, disability and gender are treated fairly and have equal opportunity. The ensuing fight for equality recognizes that historically groups of people with protected characteristics such as race, disability, sex and sexual orientation have experienced discrimination.

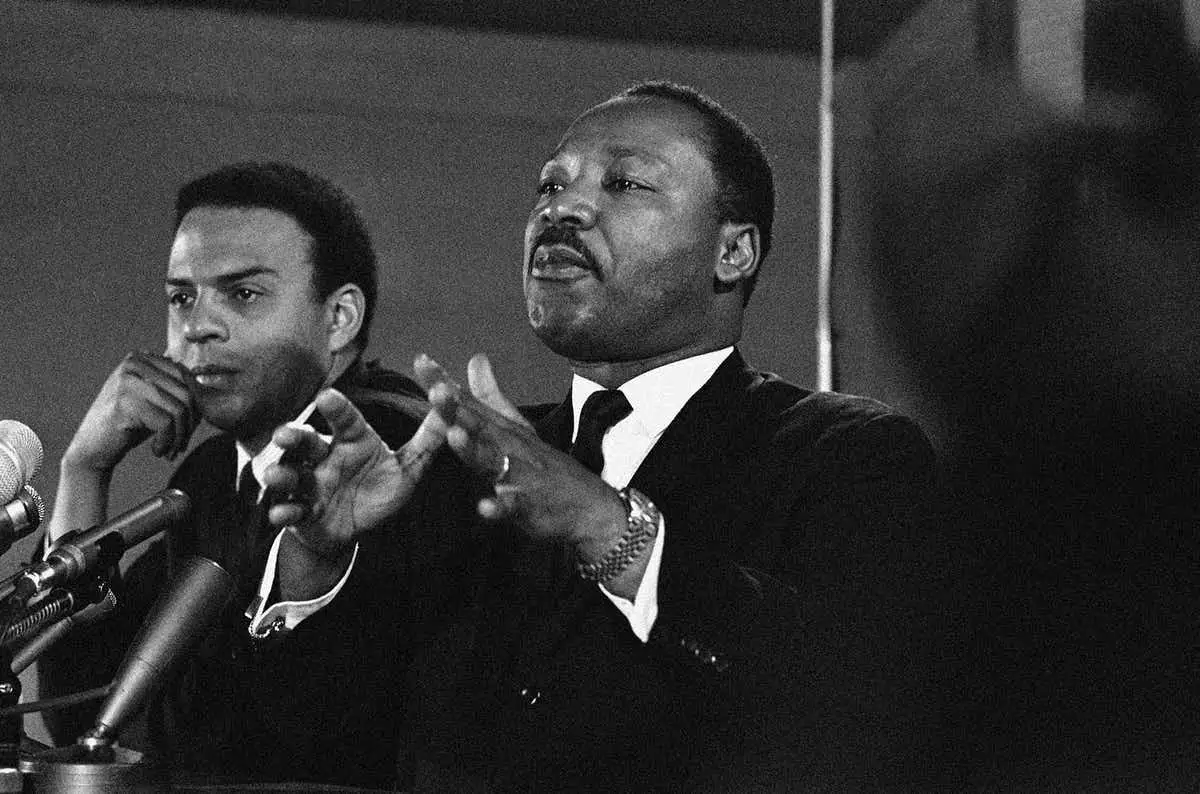

Martin Luther King Jr. often spoke about institutional and systemic racism, saying that real racial equality cannot be reached without “radical” structural changes in society. In King’s famous address at the 1963 March on Washington, he drew a parallel correlation between the struggle for racial equality and the nation’s efforts to realize true democracy comparing the failures to a bounced check:

“When the architects of our Republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir,” King said. However, King emphasized the nation had betrayed that promise to Black people: “It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned.” King warned that this failure meant the nation’s promise that “all men are created equal” remained a “dream” having yet to be realized.

Nearly 50 years after the assassination of King, The Chicago Reporter continues shining a light on racial disparities in policing, education, employment, health care and voting rights, underscoring the widening gap between the nation’s democratic ideals and its present reality.

Despite the disproportionate number of Blacks killed unjustly at the hands of police brutality and the swelling Black Lives Matter movement of 2014 after the deaths of Michael Brown in Missouri and Eric Garner in New York, research today shows that Americans remain divided over whether racial equality is a problem. While a vast majority of Americans recognize that White people enjoy racial advantages and are angry about racism in society, a substantial and growing faction post-Trump era disagrees

King said that many White people, even well-meaning people, think that equality means Black people have to improve. In which case, the election of the first African American U.S. president may lead White people to the false believe that we (Black people) have arrived and all is racially just and equal.

King noted in a speech titled “A Testament of Hope” posthumously published in 1969 that a major problem to achieving consensus was getting the White majority to understand the fundamental meaning of equality: “Justice for black people will not flow into this society merely from court decisions nor from fountains of political oratory…White America must recognize that justice for black people cannot be achieved without radical changes in the structure of our society,” King said.

But the challenge reckoning racial inequality under those terms and in many cases is that we expect the descendants of societies architects of slavery, White supremacy, Jim Crow segregation and contemporary racial discrimination that have the most political, economic, and social power to not only understand structural discrimination and inequality, but to also change the system.

The first step to reconciliation and equality is for Whites and Blacks of all ages to learn and agree on a common language and honest history of this country’s systemic racism and the historic Black movements against it—something many Whites today are not willing to begin doing or even incorporate into educational curriculum. King’s narrative on what equality means to many White people, and how some do not want to face that, is as accurate now as it was then.

The Southern Poverty Law Center published a report evaluating the educational standards for teaching about the Civil Rights movement. The report found the typical efforts on the part of mostly white legislators and educators in most states was to ignore Critical Race Theory or superficially review this important human rights movement and its racist context. The report noted curriculum was mostly limited to Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks and that only a handful of states required significant attention on the historical events preceding Black movements.

By avoiding teachings about institutional slavery, civil rights movement, systemic racism and not exploring it thoroughly, goes against what King said: “…if racism is ever to be eradicated, white people ‘must begin to walk in the pathways of [their] black brothers and feel some of the pain and hurt that throb without letup in their daily lives.”

Holding Whites accountable for the promises of liberty, freedom and equality for all made by the founding fathers was a major theme in King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. “Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation… But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.”

King’s statements on racial and social equality ring as true today as they did nearly 50 years ago. Therefore, equality remains a question that begets an answer: How can you feel our pain without learning about its origin?

Democracy dies in darkness. We rely on reader support, and your donation to The Chicago Reporter will help our investigative journalism efforts to shine a light on racial and social inequality and speak truth to power.