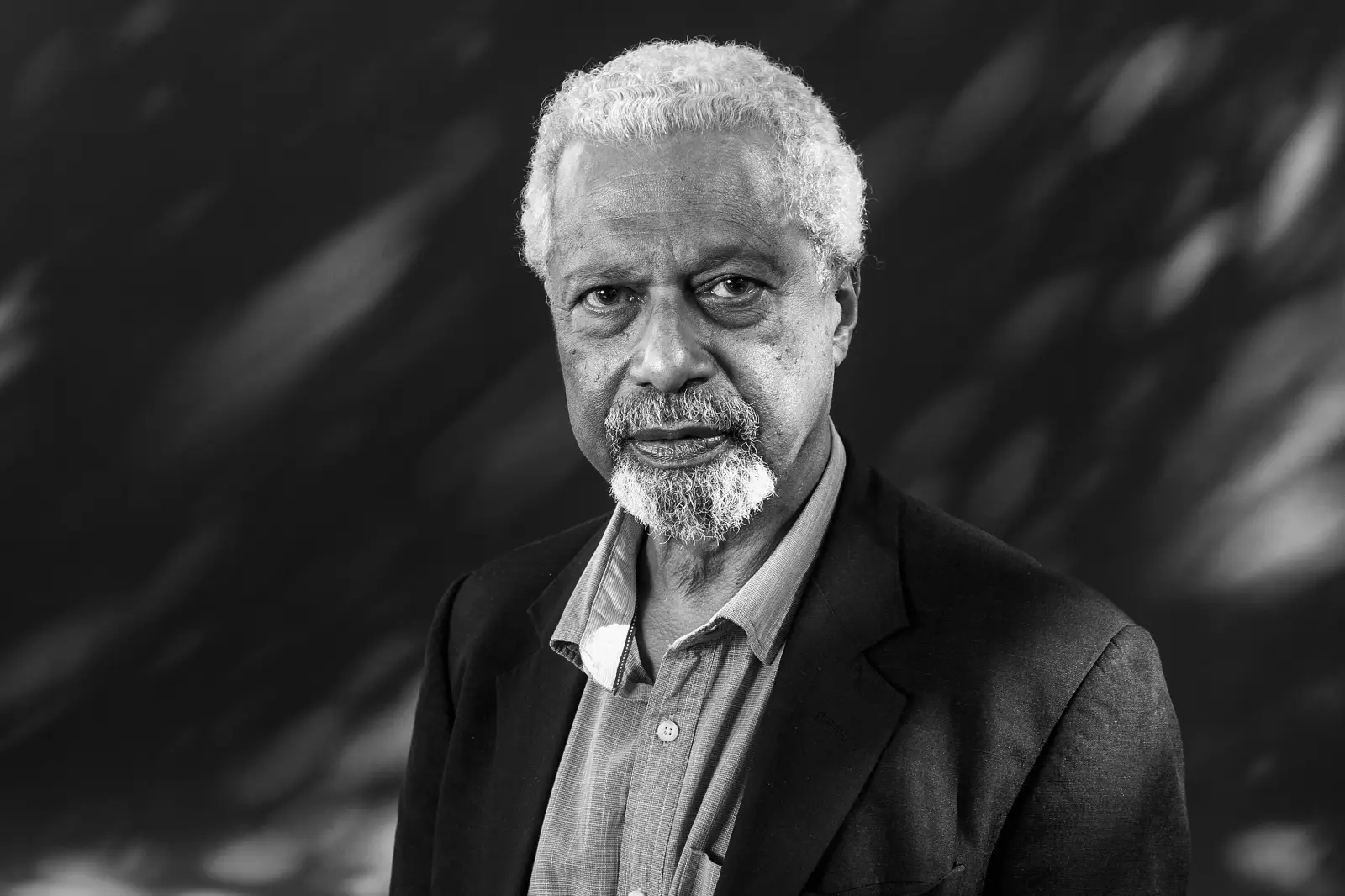

When Tanzanian novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah won the 2021 Nobel Prizein Literature last October, becoming the first Black writer to win the award since Toni Morrison in 1993, his books shot to the top of must-read lists. But in the U.S., as well as other parts of the world, the now 73-year-old author’s backlist (10 books published from 1987 to 2020) was largely out of print. American publishers immediately began bidding for reprint rights of Gurnah’s work, with Riverhead securing the rights to three books, including his acclaimed novel Afterlives, released in 2020 in the U.K. and set to arrive in the U.S. this August.

In the citation for the Nobel, Gurnah’s body of work is praised for his “uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents.” Those topics are at the center of Afterlives, a heartbreaking and sweeping story centered on the devastation brought about by Germany’s colonial rule in early 20th-century East Africa. In Afterlives, Gurnah set out to write a novel about this period partly to bring greater awareness to the brutalities inflicted on those living in East Africa at the time. The story focuses on four characters who are all touched by the war in different ways and examines the impact of trauma. Gurnah is very familiar with the landscape of this narrative—he was born in Zanzibar, now Tanzania, and fled the country as a teenager, becoming a refugee at 18 and relocating to England.

TIME is exclusively revealing the book’s cover—an intricate and layered design by Grace Han—and spoke to the Nobel laureate about winning literature’s biggest prize, his hopes for his new readership and the problems with deeming 2021 a “big year” for African literature.

When you won the Nobel Prize, you essentially became a “celebrity” author overnight. How did that feel?

To be perfectly honest, I felt like enough of a celebrity before. I have loyal readers who have been reading my books for many years, and I was quite comfortable with that. But this is global. People all over the world know about it, whether they are readers or not. The thing that’s been most amazing is the number of publishers across the world who want to publish the books in their own languages.

What was going on inside your head the moment you learned you won?

I thought, “This is a joke.” But then I found out that this is very often the response of people being awarded the prize, because it comes out of nowhere. What kind of writer would you be if you were to receive this call and think, “Oh, good. I’ve been waiting for this”?

With you winning the Nobel and Damon Galgut winning the Booker, some are calling 2021 “African literature’s big year.” What do you make of that?

It’s nonsense. It’s suggesting something to do with a phenomenon of Africa rather than these awards that have been given for the quality of the writing of those particular texts. The selection panels of these awards didn’t all get together and say, “Hey, let’s make this Africa’s year.” They selected writers for the writing, not where they came from. It’s okay if you want to make a journalistic case that this is Africa’s year, so long as it doesn’t make it seem like some kind of recognition of a region rather than recognition of the writing itself.

Your book Afterlives, which will be published in the U.S. in August, fits into many buckets: it’s historical fiction, a multi-generational saga and an epic love story. How do you categorize it?

It was really about telling something about a historical episode that has not been given enough attention. I also wanted to say something about the resolution of people to survive—how people retrieve their lives after trauma, how people come through those things and organize and shape themselves.

Like many of your books, Afterlives deals with displacement, colonization and loss. What draws you to those themes?

Partly because it’s my experience, but also because it’s very much a phenomenon of the times we live in. Writing about dislocation or strangers finding themselves unwelcome is not to invent anything. It’s to write about what’s right in front of our eyes.

What do you hope new readers will take away from reading Afterlives?

That they will have a better grasp of that historical moment and that that historical moment does not stand as a unique episode, but that it is repeated in different parts of the world—and perhaps it is repeated even in our times. Forces can appear suddenly, disrupt, destroy and leave people to find ways to recover themselves. I hope they will take away the possibility of speaking out against injustices.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.