Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

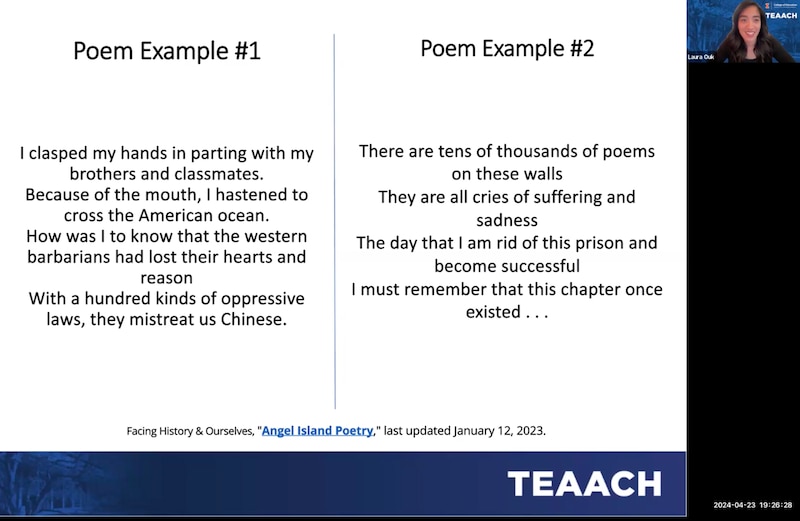

A former California park ranger traced his fingers over the Chinese characters carved onto a wall. It was as if ghosts were there, sharing their stories, he said.

The ranger was standing in the immigration station on Angel Island, the lesser-known West Coast counterpart to Ellis Island. Tens of thousands of immigrants, mostly from China and Japan, were detained there in the early 1900s. Many left behind poems or messages.

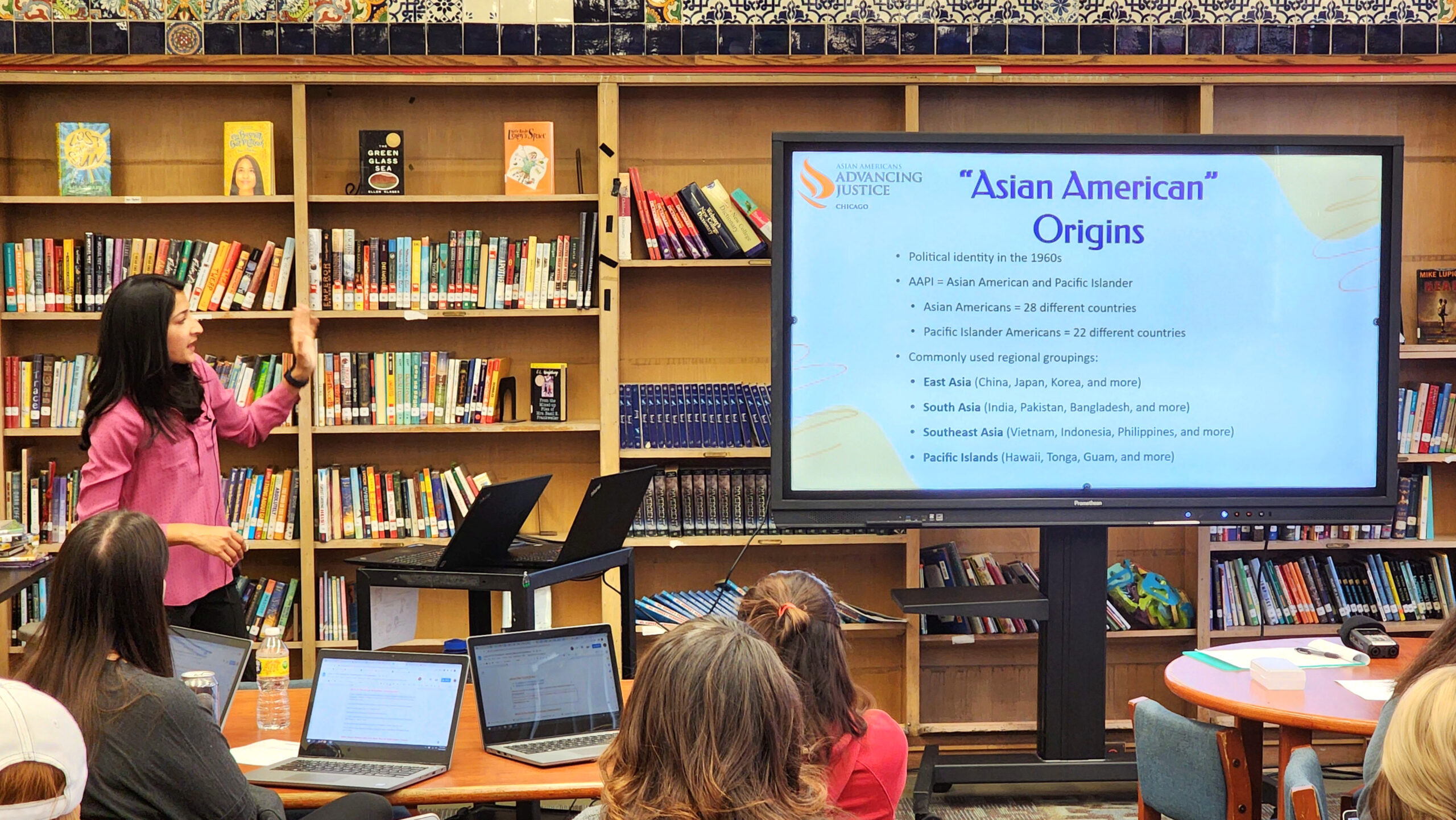

Dozens of Illinois teachers watched the ranger in a recorded video. They had gathered over Zoom to learn about how they could incorporate Angel Island and other key elements of Asian American history into their lessons. It was part of a university-led training meant to help Illinois teachers comply with a three-year-old, first-in-the-nation law that requires schools statewide to teach at least one unit of Asian American history.

Laura Ouk, one of the trainers that April evening, pulled up two poems from Angel Island and asked the teachers to read them aloud. Then she offered some sample questions the teachers could use with their students to examine tone and themes, as well as how they might connect the poetry to the works of poets like Langston Hughes and Joy Harjo.

“They really appreciate being able to see it in action,” Ouk said, “rather than just being like: ‘Here’s a resource, now good luck!’”

Across the country, advocates are pushing for American history to include more perspectives and stories. Eleven states now require public schools to teach Asian American history in some capacity, and several others are considering similar proposals. But as states and school districts adopt new curriculum requirements, educators can struggle with their own lack of knowledge, where to find quality resources — and how to fit it all into an already crowded syllabus.

The work happening in Illinois offers insight into what can help. It’s common for teachers to feel overwhelmed and think: “I need to teach this, I don’t even fully know this yet,” said Ouk, the visiting inclusive education director at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign’s College of Education and Illinois State Board of Education.

To address that, teacher trainers say they’re modeling lessons, showing teachers where Asian American voices and experiences naturally fit within existing curriculum, and sharing strategies that are useful for teaching the history of many marginalized groups.

“We don’t want teachers to blow up their curriculums,” Ouk said.

Why states are requiring Asian American history lessons

When Illinois’ governor signed the Teaching Equitable Asian American Community History Act in 2021, it became the first state with a standalone law requiring public schools to teach Asian American history. Since then, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Florida have enacted similar laws.

Half a dozen other states — California, Colorado, Nebraska, Nevada, Oregon and Utah — require schools to teach Asian American history as part of a broader curriculum, according to a 2023 report by the Committee of 100, a nonprofit tracking these efforts.

Proponents of these laws say they’re necessary because students typically don’t learn much Asian American history at school.

Eighteen states are silent on what students should learn in their history classes, according to research conducted by Sohyun An, a professor of social studies education at Kennesaw State University.

Other states focus on just a handful of events in Asian American history, An found, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act, the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, and the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Often, that instruction presents Asian Americans as powerless victims, An said, without showing acts of resistance, such as how Chinese immigrants who built the railroad protested their working conditions and pay. And it tends to be simplistic, glossing over, for instance, how U.S. and European imperialism created economic hardships that forced many Chinese to leave their home country.

“When we teach about power and oppression, we need to highlight people’s agency, resistance, and solidarity,” An said. “That’s, I think, what good history education is about.”

Collaboration is key to Asian American history training

As happens in many states, Illinois did not offer additional funding to help schools fulfill the new Asian American history requirement. So nonprofits, universities, and foundations have stepped in to offer training and support.

Ouk is part of the University of Illinois’ efforts to offer teachers both live and go-at-your-own-pace sessions. Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Chicago, a nonprofit that works on racial equity issues, launched a free training for teachers in 2022 and put together written examples of how teachers can include Asian American experiences in their reading and social studies lessons.

The organization also maintains a giant database of lesson ideas.

“We’re trying to sift through all the garbage,” said Esther Hurh, an education consultant who helped develop the training and now leads sessions for educators. “Teachers want to do this, they just need people to support them.”

Together, the university and the nonprofit trained 1,700 teachers across Illinois last school year, the first year the new requirement was in effect. It’s a good start, advocates say, but a lot more teachers still need training. Without a better understanding of the Asian American experience, experts say, it’s harder for teachers to try out sample lessons, even if they’re good ones.

During the training that Hurh leads, teachers read reflections from Asian American teachers about how it felt not to see themselves in their own schools’ curriculum. Many felt ashamed or excluded.

In one essay, a Japanese American teacher recalls that as her high school history class approached its unit on Japanese American incarceration, she readied herself to share what happened to her own family.

But the teacher sped through the lesson, and there was no time for sharing.

“When you’re negated in curriculum, that plays a huge role in how you feel and understand your connection to schooling,” Hurh said. “For a lot of teachers, that’s a very compelling argument for them to do this work. Because, in the end, they’re doing it for their students.”

The training breaks down the many nationalities and ethnic groups that fit within the Asian American umbrella. Teachers also learn about two major Asian American stereotypes — the racist “yellow peril” and the “model minority” — and how those ideas repeat throughout history.

With that groundwork laid, teachers watch several model lessons, including how they can include the story of Mamie Tape, the daughter of Chinese immigrants, in lessons about efforts to desegregate U.S. schools; how Larry Itliong, a Filipino American, contributed to the famous Delano grape strike; and how the children’s book “A Different Pond” can support teaching about the resettlement of Vietnamese refugees.

Trainers want to show teachers how they can choose literature and primary sources that not only center the voices of Asian Americans, but diversify the voices they include. Stories about Pacific Islanders and South and Southeast Asians tend to be even less represented than those from East Asia, Hurh noted.

How teachers have put their training into action

Tom McManamen, who heads the social studies department at Neuqua Valley High School in west suburban Chicago, walked away from his session with 24 pages of typed notes that he still consults.

He now looks for additional visuals as he teaches about what it means to be American. For example, he plays a video in his human geography class about a Sikh farmer in California. When his students see a man in cowboy boots wearing a turban, they often exclaim: “Oh, wow!”

High school teachers across McManamen’s school district and county are getting trained, too. One colleague used what he learned to incorporate the murder of Vincent Chin into lessons about immigration and the auto industry. Another used political cartoons to teach about Asian American stereotypes. The training helped teachers know what to look for as they searched for resources that weren’t shown during the training, too.

“What I love is when I hear them brainstorming over it,” McManamen said, “What used to be a difficult conversation, like: ‘How do we do this?’ It’s now: ‘Oh, you could do this, we could do this! I ran across this when I was watching TV that was totally a great example!’”

Still, even with this kind of training, experts in the field admit it can be difficult for teachers to cover as much ground as they might like, especially if their state also has requirements around teaching Black, Latino, and Indigenous histories.

An, of Kennesaw State University, noted that teaching students skills so they can conduct historical inquiries on their own helps them keep learning. That could include showing students how to find stories that challenge the dominant narrative, read between the lines of primary sources, or look for examples of resistance whenever there is oppression.

“We don’t have to teach every single topic,” An said. “One lesson can do so many things actually, if it’s well-done.”

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.