Fans of HBO’s Lovecraft Country or Watchmen know something that this country has largely tried to forget: the Tulsa, Okla., race massacre, whose centennial falls on May 31—Memorial Day—in this year of racial reckoning. Both series depicted the massacre, where a white mob, inflamed by rumors that an African American teenager, Dick Rowland, had assaulted a white woman, murdered up to 300 Blacks.

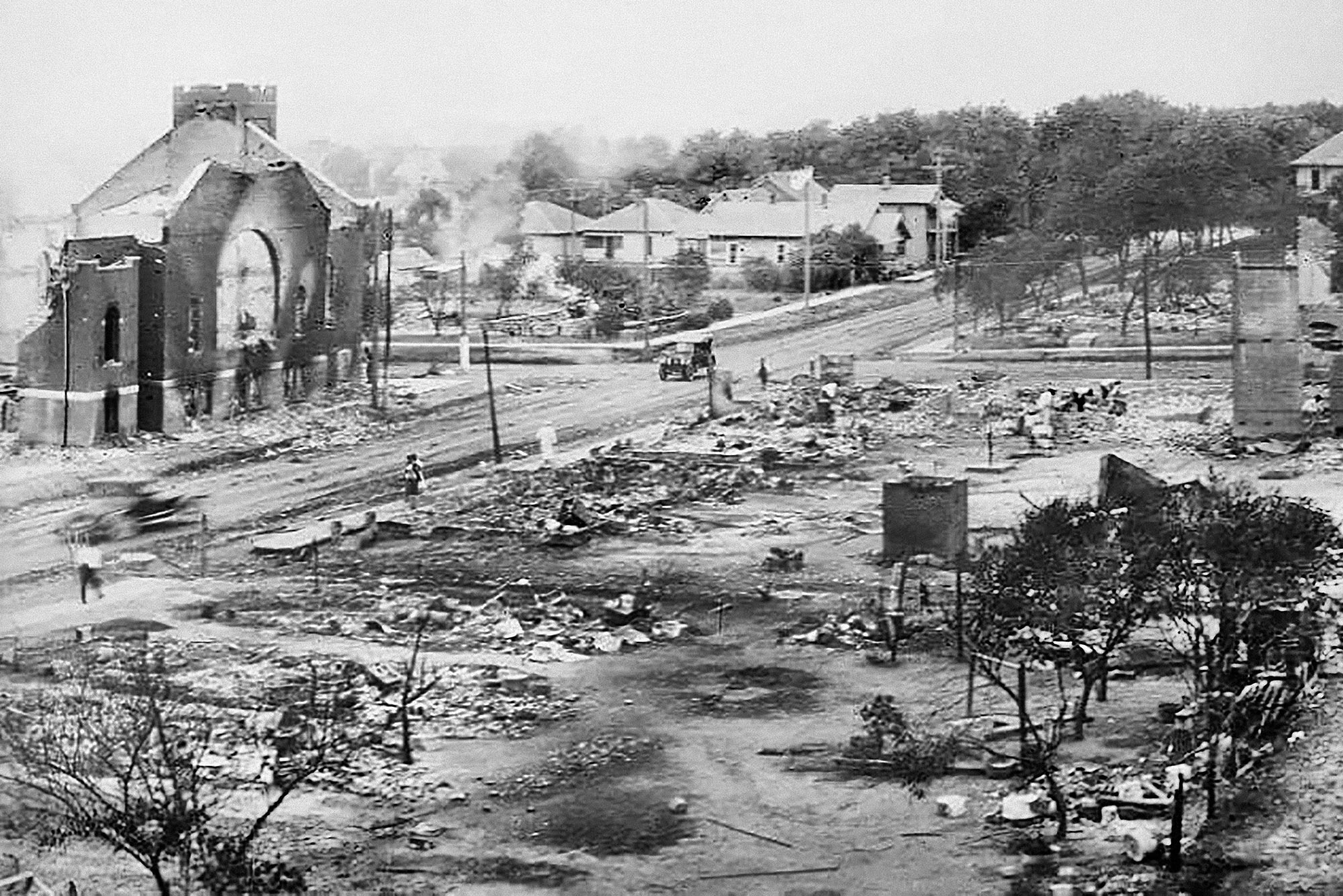

“He had apparently tripped and grabbed hold of a young white woman elevator operator,” says Paula Austin, a College of Arts & Sciences assistant professor of history, of African American studies, and of women, gender, and sexuality studies. “He had to get on that elevator, because he worked in a white-only shoeshine parlor on Main Street in segregated Tulsa and had to go into the Drexel building to use the ‘colored’ restroom. Dick was eventually exonerated and fled the city.” But the Greenwood section of town, dubbed “Black Wall Street” for its robust economy, was razed to a smouldering 35 blocks.

Austin, who teaches and researches anti-Black violence of the 20th century, discussed Tulsa in her recent book Coming of Age in Jim Crow DC (New York University Press, 2019). She parsed the tragedy’s lessons for our current national antiracist moment with BU Today.

Q&A

WITH PAULA AUSTIN

BU Today: How widely remembered today is the massacre, and—if the answer is “not very”—why is that?

Austin: It depends on what “widely” means. Many of us, some of us in the profession, but also descendants of this and other episodes of racial violence, absolutely know about this and reference it in our discussions about the history of racial violence in the United States. And the ways that violence has been perpetrated and/or supported by the state and often involved state actors. In the Tulsa case, the police deputized lots of folks who were Klan members and had taken part in lynch mobs to “protect” the Greenwood community.

The opening scenes of Watchmen vividly and horrifically depicted the violent attack and all-out war on Greenwood’s Black community, and the devastation that it wrought. The rest of the episodes sort of perfectly gestured towards the long afterlife of racial violence, both in terms of the possibilities for reparations, but also in terms of the ways structures of white supremacy and its ideologies endure.

In the long, sad story of American racism, how important is what happened in Tulsa?

Very? There is so much racial/racially motivated/racist/anti-Black violence that undergirds the history of the United States, [including] settler colonialism and an evolving racial capitalism, both of which require violence and domination. While it’s true that some of this history is unknown by some, other people willfully dismiss this history, and others fight hard to make sure this history is not taught at any level of K-12.

Are there lessons from Tulsa—about why it happened and how to address the underlying racism—that might instruct us in 2021 as we try to address systemic racism?

My experience as a historian is that there are some people who do not want to learn, who resist this knowledge, or who call knowledge of racial oppression “a threshold concept” and then never cross the threshold. Still others may accept that something happened, but refuse to take seriously the systematic nature of these occurrences, restoration, repair, or justice of any kind. There are others who fight to keep knowledge away from other people, who spread historical inaccuracies. They appear to be the same people who desire to maintain exclusive access to certain aspects of a democratic society.

As someone who is not only Black but teaches US history with a focus on the development of the concept of “race” and the structures of racism, this last year has been especially exhausting. Simply, the lesson of the Tulsa massacre is that it happened; a thriving Black community was destroyed. And that it is not the only Black community with this history, or the only marginalized and minoritized community in the United States to whom some version of this kind of destruction, dispersal, dispossession, death-dealing has been perpetrated—often supported or led by federal, state, or local/municipal government.

In terms of Tulsa, it wasn’t until the late 1990s that any kind of process was entered into to investigate what had happened, what had been lost, what was owed, how it had been intentionally hidden. The [Oklahoma state] reportthat was produced lays out more than the horrific violence done by white rioters over those couple of days. What stands out, against the backdrop of our contemporary moment, is the decades leading up to it, [beginning] at the end of the Trail of Tears to the segregation and anti-Black voter suppression, all before that fateful day Dick Rowland got on an elevator.